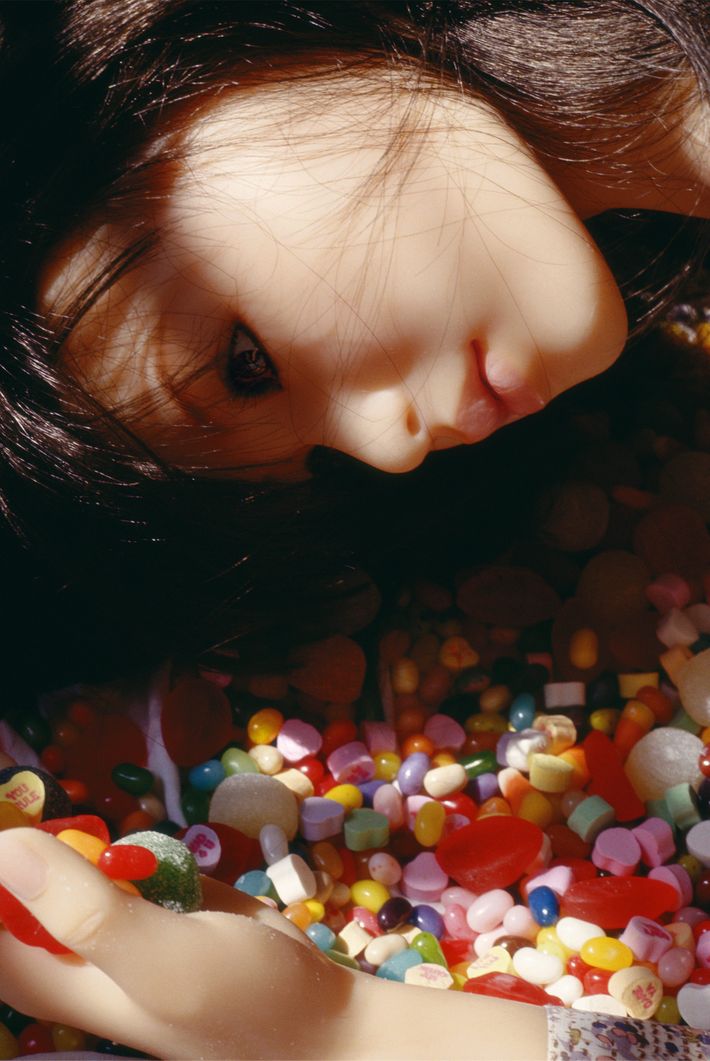

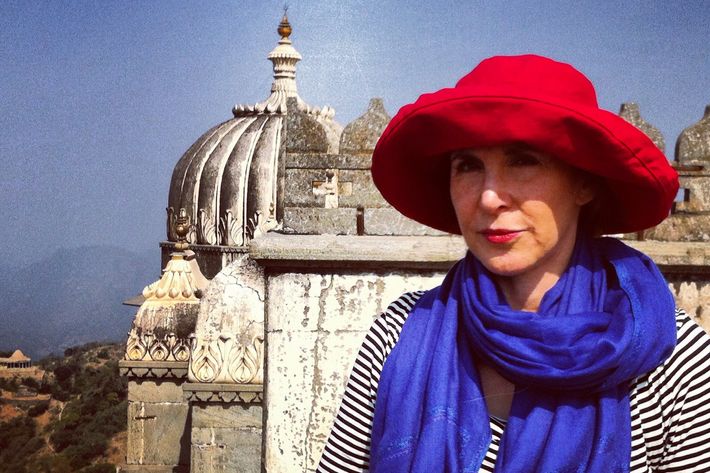

Artist Laurie Simmons is famous for off-kilter photographs staging inanimate objects, like diminutive dolls and ventriloquist dummies, shot in domestic, often surreal settings. For her newly released book, The Love Doll, Simmons introduces a new, larger scale into her work by photographing a life-size human doll — an “excruciating” process, as she explains it, due to its weight. She first discovered her latest subject while on holiday in Japan with her daughters, Grace and Lena Dunham, and the book captures the interaction between the photographer and a doll for nearly five weeks over a two-year period. As time passes, the portraits grow increasingly intimate, much like a human connection between two strangers. We spoke with Simmons about that relationship, plus how she handled the sexual context of the doll, especially as a female artist. Read on, then click through for exclusive photos from her series.

Throughout your career, you’ve shot dolls, ventriloquist dummies, and other various inanimate objects in a humanistic light. Where did the idea of shooting these sex dolls originate from?

It wasn’t something I was consciously looking for. I spent most of my summer in 2009 in Japan; first with my daughter Lena, and then I went back with Grace. [Grace and I] were in a bookstore and she found this little poster of a sex doll. I got really excited because I realized it was a life-size doll, but beautifully articulated. We tracked it down and went with a Japanese friend, who acted as an interpreter, and I had to have one to photograph. I wasn’t looking for this doll, it kind of found me.

Aside from the sheer size of the doll, how is this a progression from your early works from the 1970s?

The most striking thing was how much I’d wished to shoot this fantasy of a life-size doll. The doll wasn’t light as a feather and it was really difficult to move around, which meant that I had to have more people in the studio with me. The photographs look really dreamy, but making them was really excruciating, it was more challenging than when I was alone in the studio with a couple pieces of doll furniture, one light, and a tiny doll.

Why did you decide to move onto shooting a larger figure?

All these years of shooting small things and dolls; I was frustrated every time I tried to turn the camera to a human subject. It never was quite right for me. There was something missing, always training the camera on these smalls things, so having a human-sized doll was kind of a dream come true. Although, I don’t know if I consciously articulated that dream prior to finding that doll.

Is there a reason why you refer to these dolls as love dolls in the book and not sex dolls?

That’s what they were called in Japan. I didn’t make that up. They were never called sex dolls on the website, they were called Love Dolls.

So, this book highlights your “relationship” with the doll over a specific period of time, what were the parameters of this “relationship”?

I looked at the doll and I thought about how long it always takes me to get comfortable with a subject, and how long I have to shoot before I get a photograph that I’m really satisfied with. I had this awareness that I already know how to take a picture, so the documentation of getting to know the doll would be more interesting than just waiting until I was totally comfortable with the doll to see what kind of pictures I would get. I decided there was something to look at from day one, and when I made that decision, I started to document the days of shooting. And then I thought, I could also understand what was different between day one and day 100 [of photographing it]. I’m not at day 100 yet.

Over time, your images with these dolls become increasingly intimate; how did you time this development?

It just unfolded. In the beginning, I really was treading around the thing delicately. I really didn’t know how to work with it, how to move it, how to relate to it, and I became more and more comfortable and the pictures became more elaborate in the situations. I would wake up and I had to dream up what the scenarios would be for the day. As I moved through different rooms of the house and bought or found different costumes, it became more and more complex. Also, maybe in a sense, more and more real.

Basically, it arrived naked with no identity and it was up to me to do everything — to decide what clothes the doll wore, introduce the doll to various household, daily tasks or situations. Everything was up to me. It was kind of like building a house from the ground up instead of renovating it.

It sounds like you approached these dolls as if they were almost like real humans.

Only in my work. My relationships with the dolls existed in the pictures. I absolutely had no interest in the dolls outside of [my work]; they didn’t become members of the family.

I hope not.

People have very odd ideas what it would be like to have a life-size doll in your house. Also, people do anthropomorphize their dolls and objects. Kids do that in childhood and some adults do that. People put funny hats on their dogs, people do all sorts of things. This was a prop. And it was only when I was working that this kind of stab at reality for this character happened. When the shoot was over, it was over.

You did a good job at creating an atmosphere around these dolls, I could almost sense personalities. Color also played a big role in the images.

For the yellow picture, I grabbed [the] Donald Judd book; it was a beautiful shade of yellow and a couple of people who wrote about the [photograph] thought it was a heavy-handed reference to a certain period of art, [but] it absolutely was — sorry to say — about the beautiful yellow book.

As the book progresses, you introduce a second doll into these images.

I thought as soon as I introduced another character, there could be a kind of human interaction. Before it was one woman, but suddenly I was thinking about friends and sisters. The interesting thing is, there was only one photograph with two of them together that I actually used [for this book]. That’s something that is out ahead of me [to photograph the two of them together]. I found it really difficult. I tried lots of scenarios and setups. The dynamic of the relationship was crowding the photos.

On day nineteen, you also dressed one of the dolls in a pair of Peter Jensen knee-high boots. Was there a reason behind bringing the element of fashion?

Peter had given me the boots and I just loved them so much. It came from a collection that I was the muse for. They were just something I could never figure out [how] to wear; they’re white, over-the-knee, the heel is four-to-five inches high and they just were not viable for my wardrobe. Putting it on the doll, number one, on a formal level, allowed me to shoot a very white picture, which I wanted to do. Number two, it gave me a way to almost live vicariously through the doll wearing those boots.

Again, it goes back to your interest in capturing color. I’m curious to hear, how did you traverse through the sexual context of the dolls, as a female artist?

I really, in the end, had to turn a blind eye to it. I found what I wanted in terms of prop. I both ignored and denied what the doll was created for. The box that arrived with the genitals and lubricant were put into deep storage. We would laugh in the studio, we’re not a love doll rescue organization; we have two of them. I had to really think of the love dolls the same way about dolls I had used [in my work].

The book ends with a series of the dolls dressed in Geisha attire. What was the meaning behind these images?

I felt like I brought these dolls from Japan, and I was Americanizing them, putting them in my life, doing what I felt comfortable with. But I felt like the lure of where they came from — in my whole childhood fantasy about Japanese Geishas — overtook everything. It’s almost like the powerful pull of where the dolls came from and my own history, my own personal mythology of all things Japanese, I just had to go there.

The final image is of your studio manager, Rachel, and her gorgeous geisha back tattoo, alongside the doll dressed in traditional Geisha attire. In the book, you mention that it was first time you felt like a human could be shot alongside the doll, could you clarify?

I had worked in Connecitcut with an assistant, Joanna, who is Korean and the same size as the doll and very beautiful. I tried to shoot the two of them together, [but] they were exactly the same height; when Joanna had stepped into the picture, she was so much more beautiful and human and stronger-looking than the doll, so I had kind of given up. But somehow, when I discovered Rachel had this tattoo of a young geisha, I felt like I could do something.

Do you have plans to continue your “relationship” with the dolls?

Yeah, there are more pictures coming. The Asian love doll has been in the water and done all these things, [so] that the body of the doll is becoming degraded in some way. I’m in the process of having this amazing tattoo put on its back and it seemed like the next step of the journey.