It starts with claiming your spot on the riser. Then you need something to stand on to make sure you have a perfectly clear view; something for the photographer behind you to stand on, so that he can aim his camera above your head. Then you wait in position as the editors, buyers, and front-row stars come trickling in to their seats.

Eventually the music starts, and light floods the runway. Then the first girl steps out, and for the next fifteen minutes, all that exists is the models, your hands on the camera, and the continual fluttering sound of dozens of shutters going off around you.

This is life in the photographers’ pit, the shadowy area at the end of the runway from which all Fashion Week runway images emerge worldwide. I’m here as the guest of photographer Chris Moore, the founder of Catwalking.com, who has been documenting designer collections since the late sixties.

If you thought the secret of eternal youth was getting enough rest, Moore will prove you wrong. He was born in 1934 and still works twelve-hour days at all the major fashion events, carrying equipment and standing precariously on a small box for hours on end. In the weeks before our day together in London, he has shot all the menswear shows, Paris Couture week, and New York Fashion Week. He will go on to Milan and Paris again after London for the women’s shows. He has significantly more stamina than me, and I’m 50 years his junior.

“They do say Fashion Week is exhausting, but the truth of the matter is that work keeps you young and fit,” he insists. “My legs and knees are dodgy, but I try to ignore that — I now have a young man who helps to carry my bags in London.”

That young man is Dale, who has worked four seasons with Moore and finds the job enjoyable if not glamorous. “Coming to fashion shows is the fastest way to disillusion yourself about them,” he says. “You wait around for ages, and then they’re over in ten minutes — it’s like a premature ejaculation.”

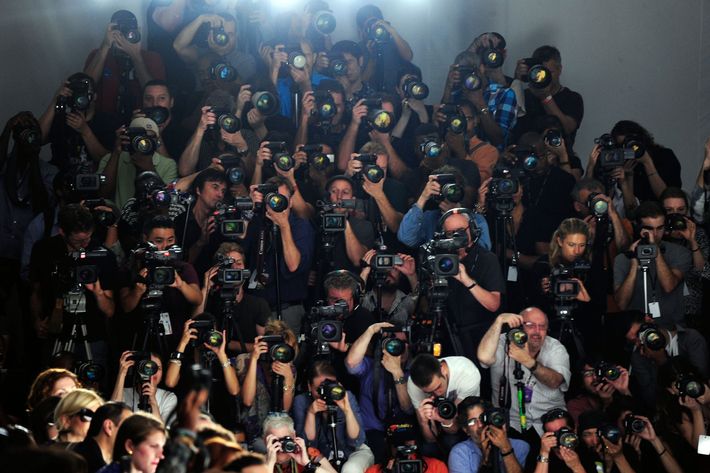

In the pit, everyone is crammed in rows, shoulder to shoulder, lenses poking through between heads. They all bring boxes or stools for those extra few inches of height, and at the Somerset House tent, the main venue for London Fashion Week, stepladders are lined up along the back wall. A sign says ‘Photographers stand on ladders at their own risk’, but nobody seems worried about risk. They are only concerned with getting the shot.

Although those in the pit are often professional rivals, there’s a friendly atmosphere. Equipment and boxes are borrowed; favours are offered and accepted. If one has a disaster and fails to get the shot he needs, another might share his images. But there’s a firm hierarchy too. “It’s a little bit mafia,” says Moore. “The people who cover everything look after each other.”

There are significant advantages to being in that group. Top-priority photographers — from Catwalking, Vogue, Style.com, WWD, and a few other agencies and publications — are summoned at 11 a.m. the day before London Fashion Week begins, to claim their space in the Somerset House pit and mark it with tape. For the other, more unofficial venues, Catwalking hires a group of “marker-uppers” — young freelancers who travel round London first thing in the morning, and talk their way past the guards to mark out their photographers’ preferred spaces with tape. “In Paris,” he explains, “It’s sometimes so competitive that the markers have to sit in the space until the photographer arrives,” which can be as long as eight hours, resting on risers.

Despite all that effort, there are only occasional arguments. Improvements in technology have actually made life easier for runway photographers — digital cameras can compensate for poor show lighting, for example, over which they have no control. But it’s also leveled the playing field in a way that frustrates Moore. “Catwalk shots all look the same these days. It’s boring,” he says. “Sometimes I take wide-angle pictures, but there’s not much demand for them — occasionally they’re used for openers. The International Herald Tribune used one of mine last week, from the Thom Browne show.”

Moore is developing a cold, which happens every season. And he is constantly being asked when he will retire. “It’s obscene for somebody of nearly 80 to be doing a boy’s job,” he says, “but it gets in the blood. There are some shows so good that they make the hair on the back of your neck stand up — that’s what you’re always hoping for.”

He particularly remembers two “absolutely marvelous” shows that Hussein Chalayan held at Sadler’s Wells Theatre in London, and several Alexander McQueen shows. At the one held immediately after the designer’s suicide in 2010, Moore was the only photographer invited. “Everyone was in tears, including me.”

While I’m watching him, I stand to one side to avoid disrupting the photographers — but twice, Moore sneaks me in to stand next to him, in the center of the pit. “Stay right there,” he tells me. We are all packed so closely that if I move left or right an inch, or stand on my tiptoes, I could ruin someone’s shot.

It hits me that a show is designed to look its best from exactly where we’re standing. We have the perfect view. Pit photographers aren’t treated with the same indulgence as most guests at shows — but they’re uniquely privileged. It’s into their eyes that the models direct their smouldering gazes, and it’s only in the pit that you feel the show is meant entirely for you. It’s an addictive feeling — one nice enough to keep a man from ever retiring.