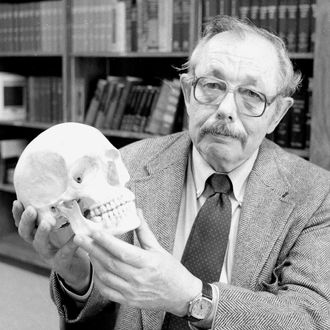

Clyde Snow, a legendary forensic anthropologist, has died at 86, reports the New York Times.

He was seen as a godfather of the field, which differs from regular forensics in that it’s performed on the bodies of folks who have been dead awhile. Snow examined the corpses of John F. Kennedy and Joseph Mengele, “reconstructed the face of Tutankhamen” with the help of medical artists, and, in general, lived a life that reads something like a cross between the main character in Bones and Dos Equis’s Most Interesting Man in the World.

A Los Angeles Times profile from 2001 helps give a sense of the full impact of his work:

From 1976 to 1983, more than 10,000 Argentines disappeared. Many were taken to detention centers and never heard from again. Other desaparecidos, or disappeared ones, were buried in graves marked “N.N.” for no nombre, or no name.

Before Snow’s arrival in Argentina, untrained workers had plowed into the mass graves, inadvertently destroying evidence and skeletal remains.

“They were out there with bulldozers, digging up cemeteries. It was a mess,” Snow said.

He realized he had to train Argentines in proper excavation techniques so evidence could be preserved.

“Word had gone out in the student community that an old gringo needed some help,” he said.

Local university students hesitatingly volunteered to aid Snow. But they expressed fear about the seemingly ghoulish undertaking. They had many questions for him, and, in response, he gave them moral support.

With Snow’s help, the students persevered. They uncovered evidence of executions and brutal beatings: bullet holes in skulls, “perimortem” (near the time of death) fractures in arms and finger bones, typical of defense injuries. They helped identify desaparecidos in mass graves.

Snow eventually served as chief witness for the prosecution of several Argentine generals and admirals. At least five were convicted and imprisoned for their participation in the killings. Snow also helped Argentina’s human rights undersecretariat launch the country’s national forensic science center.

He also conducted similar investigations in response to massacres in Croatia, El Salvador, Iraq, and elsewhere. So while forensic science is cool in its own right, what with all its traveling to exotic locations and brushing dirt off of bones and so on, it was the deeply moral aspect of Snow’s work that made it so compelling. Faced with dictators and maniacs who thought they could cover up their crimes and forever escape accountability, he showed them otherwise.