Think back to the last time you heard a hymen or a scrotum lovingly described. Have you ever? There’s a lamentably utilitarian slant to the way we talk about genitals these days. Our language might be clinical or obscene, but it’s rarely interesting or companionable; one rarely hears the hymen described as “the great Clove Gilly-flower when it is moderately blown” (as Helkiah Crooke did in 1615) or imagines the cervix the way 17th-century midwife Jane Sharp did, as “the head of a tench, or of a young kitten.” Our language for sex is impoverished, but so is our language for the relevant parts.

Things could be otherwise, and in 16th- and 17th-century England, they were: The anatomy books and midwifery guides of the period are rife with weird, creative, wonderful formulations for the reproductive organs. The key difference between then and now is that male and female genitals were imagined as identical parts, just somewhat rearranged. Jane Sharp — the midwife who sees young kittens in cervixes — puts it best, I think: “The Matrix is like the Yard turned inside outward, for the neck of the womb is as the Yard … and Stones are like the Cods, for the Cods turned in have a hollowness, and within the womb lie the Stones and seed vessels.” In other words, the vagina and uterus were basically an inside-out penis, with testes and ovaries reconfigured accordingly. (If that’s unclear, here’s an NSFW illustration of this account of the female reproductive system — its phallic qualities will be obvious.) That’s a major conceptual shift in what we talk about when we talk about sex. If you consider a vagina a penis turned inside out (rather than just a hole for a penis to fill), sex becomes symbolically different, and gender gets a lot more flexible. Men and women are no longer opposites — they become variations on a single gender.

17th century male and female anatomical models.

Natural philosophy was coming into its own during this period: Andreas Vesalius published his definitive guide to human anatomy with its famously dramatic poses in Italy in 1543. The Royal Society was founded in 1660. All over Europe, curious pioneers were making observations, conducting experiments, and trying to generate not just explanations but metaphors that explained the relationship between nature and society — bees, for instance, were nature’s argument for the monarchy as a system of government. Above all, though, the natural philosophers were trying to come up with a set of scientific best practices and reconcile new discoveries with classical wisdom.

The idea of men and women as inverted versions of each other — or warmer and cooler products of the same basic ingredients in the womb — dates back to the Greeks. That understanding of gender survived even as knowledge of anatomy increased, and its symbolic and cultural consequences in early modern England were huge. If men and women both had essentially the same parts, they both produced “seed.” If they both needed to achieve orgasm in order for that seed to be released and conception to occur, then female desire was essential to the human race. So was female pleasure, the pursuit of which formed a significant component of 16th- and 17th-century guides to anatomy and obstetrics. That logic shaped the cultural understanding of how sex worked. (It wasn’t until the 18th century, with the unhappy discovery that women could get pregnant while unconscious, that female pleasure fell out of our modern understanding of reproduction.)

And since women were getting pregnant all the time, it followed that the female libido must be enormous. If our current gender myth is that men always want sex and women want relationships, the stereotype back then was that women were leaky, undisciplined, and sexually insatiable. Thomas Laqueur named this philosophy the “one-sex model” and attributes it to the new anatomy emerging in England at the time that displayed, “at many levels and with unprecedented vigor, the ‘fact’ that the vagina really is a penis, and the uterus a scrotum.”

If male and female sexual functions tended to blur, so did the corresponding analogies that explained fertilization. Our current metaphor for conception is weirdly retrograde: The large, passive egg resists the onslaught of marauding sperm, most of whom die in battle. There are lots of other ways to tell that story: Eggs are actually plenty active, and sperm are themselves penetrated by bicarbonate ions in the female reproductive tract long before they do any penetrating, but the point is that, our fantasies of objectivity notwithstanding, our gender myths still distort our biology.

Early modern England saw conception as more drawing-room drama than fantasy epic; basically, sperm are shy and retiring and likely to glumly depart unless they’re actively made to feel at home. Robert Barret, the author of another book for midwives published in 1699, advises women trying to conceive that even a vagina without “defects” (of which there are many) doesn’t guarantee conception unless it observes the rules of hospitality, and sperm are finicky guests:

If their Womb be cold, and the Seed be not received with some welcome warmth, then it slips out again for want of kind Entertainment. Or if the Womb be moist, by reason of the Seed’s being choked and extinguished in the prevailing moisture, which is commonly accompanied with a cold temperature; or if the Womb be too dry and hot, for then the Seed is burnt up and exhaled.

(If you were disinclined to entertain sperm kindly and wanted to remain child-free, however, one Cosmo-style tip — in a bawdy publication called The Wandring Whore — is to pee the seed away. “I settled on the Chamber-pot as soon as ever he was off,” a sprightly prostitute named Juliette says of her latest client, “till I made it whurra, and roar like the Tide at London-Bridge.”)

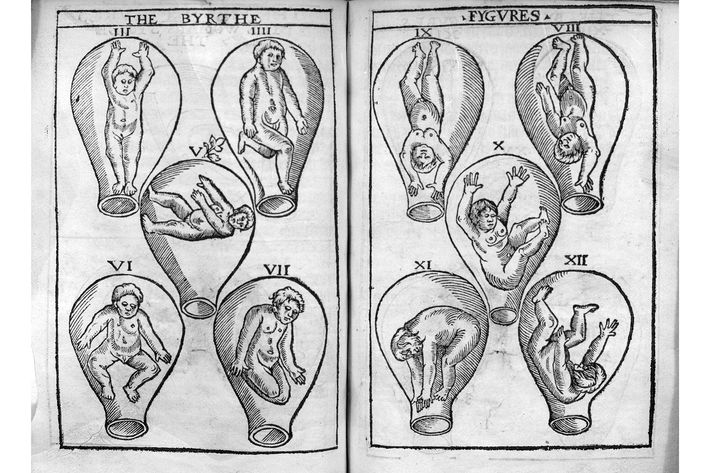

17th century medical illustrations of fetal positions in the womb.

None of this means that misogyny wasn’t alive and well. Thomas Nashe’s description of a lover’s vulva in the 1590s is far from enthralled:

[it] hath his mouth beset with ugly briars,

Resembling much a dusky net of wires.”

For Nashe, the vulva’s “ugliness” defeminizes it; the mouth beset with briars is “his,” not hers. Women who drifted into traditionally masculine realms definitely had their gender questioned, too — even (and especially) seamstresses, who performed a feminine task with a phallic tool. Moll, the hilarious, gender-bending roaring girl from the play of the same name, accuses a Mistress Openwork of “pricking out a poor living” with her needlework and sewing “many a bawdy skin-coat together.” The threat of the seamstress was practical as well as metaphorical: James Grantham Turner has shown that new forms of female agency in early modern London — particularly economic — were deeply threatening to the status quo. The market was resistant to the concept of entrepreneurial women, and that resistance equated female economic participation with promiscuity. According to this logic, “independent female enterprises — schools, lodging-houses, catering services, and luxury shops — must be covers for prostitution,” he writes, “and the only ‘commodity’ a woman can sell is herself.”

Perhaps fittingly, if seamstresses are whores, vaginas can be clothes. In The Roaring Girl, a Thomas Middleton and Thomas Dekker play first published in 1611, a hapless husband thinks another man is sleeping with his wife and begs his rival to stop “wearing” her: “Would not you scorn to wear my clothes, sir?” he says. “Then pray, sir, wear not her, for she’s a garment so fitting for my body, I’m loath another should put it on.” Then there are the more familiar economic metaphors. A prostitute “enhances” the price of her “commodity.” “Trust to no pockets or purse,” says Magdalen to Juliette in The Wandring Whore, “but that which is cut between her Legs.”

It’s worth noting that as these metaphors get more utilitarian, they also become more hostile — a purse is a lot less evocative than Jane Sharp’s “Gilly-flower half-blowne.” Those in closest contact with literal genitals — Sharp, Barret, and other anatomists — seem to be kindest to them. Jane Sharp’s description of the vulva and vagina is sort of lovely:

At the bottom of the woman’s belly is a little bank called a mountain of pleasure near the well-spring, and the place where the hair coming forth shews Virgins to be ready for procreation… Under this hill is the springhead, which is a passage having two lips set about with hair as the upper part is.

Sharp is downright prosaic compared to Barret, for whom impediments to conception include — besides fastidious sperm — a “vicious conformation of the Womb” or a too-narrow vagina: “Sometimes the Vagina or Neck is so narrow, that it cannot make way for the entrance of the Yard,” he writes, then dips back into the language of hospitality: “It knocks in vain at the Door, and meets with such resistance in the anti-chamber as obliges it to retire.” To his credit, Barret identifies just as strongly with the narrow vagina: “the Passage being so narrow, she cannot receive the Man, or his Seed, and is depriv’d of the Benefit of Coition.”

A 16th century drawing of a midwife assiting a mother to be.

If we can learn anything about this range of vaginal symbols it’s that the organs themselves become worthy objects of sympathy under the one-sex model and that this effect is greatest at the scientific (rather than the poetic) end of the rhetorical spectrum. If Nashe genders the vagina itself male and ugly in his poetry, Sharp’s vision of the cervix as the head of a tench in her guide for midwives feels winky and familiar, and Barret’s feeling for the locked-out penis amounts to the kind of empathy you’d have for a friend down on his luck. What’s most interesting, though, is the way these small touches — which amount to imagining the genitals as active partners rather than passive and active principles — add up to an entire alternative narrative about gender and desire and sex, complete with sexually appetitive women, timid sperm, and active, hospitable uteri. It invites us, too, to consider not just the words but the metaphors we accidentally import into our own anatomies, to rescue our biological myths from the 1950s and make our analogies as collaborative and mutually pleasurable as the parts that inspire them.