Users on OkCupid exchange about 4 million messages a day. Of course, they do so with a special purpose — dating — but the interface provides no specific prompt and enforces no limit on what or how much anyone types. Think of it as Gmail for strangers: the communication on the site is about two people getting to know each other; the romance comes much later, offline.

Outside researchers rarely get to work with private messages like this — it’s the most sensitive content users generate and even anonymized and aggregated, message data is rarely allowed out of the holiest of holies in the database. But my unique position as co-founder of OkCupid gives us special access.

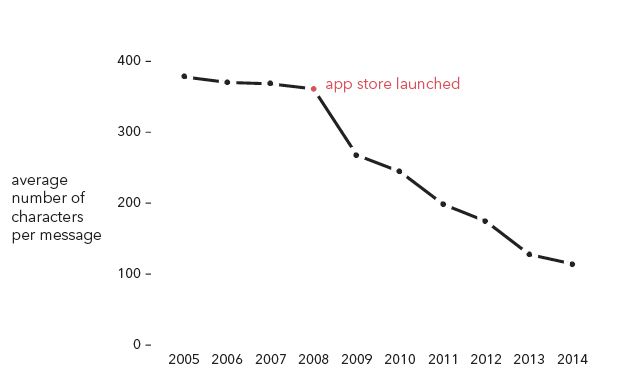

First, the site’s decade of history lets us see how technology has altered how people communicate. OkCupid has records from the pre-smartphone, pre-Twitter, pre-Instagram days — hell, it was online when Myspace was still a file storage service. Judging by messaging over all those years, the broad writing culture is indeed changing, and the change is driven by phones. Apple opened their app store in mid-2008, and OkCupid, like every major service, quickly launched an app. The effect on writing was immediate. Users began typing on keyboards smaller than their palm, and message length has dropped by over two-thirds since:

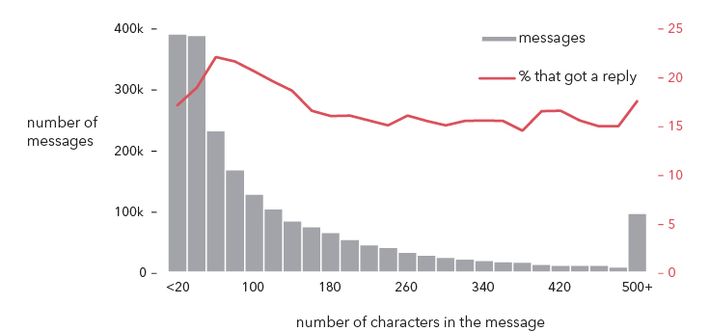

The average message is now just over 100 characters — Twitter-sized, in fact. And in terms of effect, it seems readers have adapted. The best messages, the ones that get the highest response rate, are now only 40 to 60 characters long.

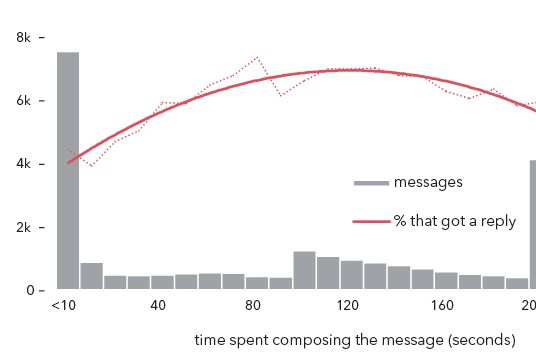

By considering only messages of a certain length, and then asking how many seconds the message took to compose, we can get a sense of how much revision and effort translates into better results. Below are messages between 150 and 300 characters, plotted against how long they took to write. As you can see, taking your time helps, up to a point. But the downward bend of the trend lines is a wingman in numbers, saying don’t overthink it!

Now, the first vertical on the left, the messages that took no more than ten seconds to write, represents an inordinate amount of the whole and should raise some eyebrows. It raised mine for sure, and at this point I’m so jaded my face is frozen — Botox has nothing on ten years working at a dating site. How are so many people typing messages that long that quickly? The short answer is, they’re not, and here’s how I know.

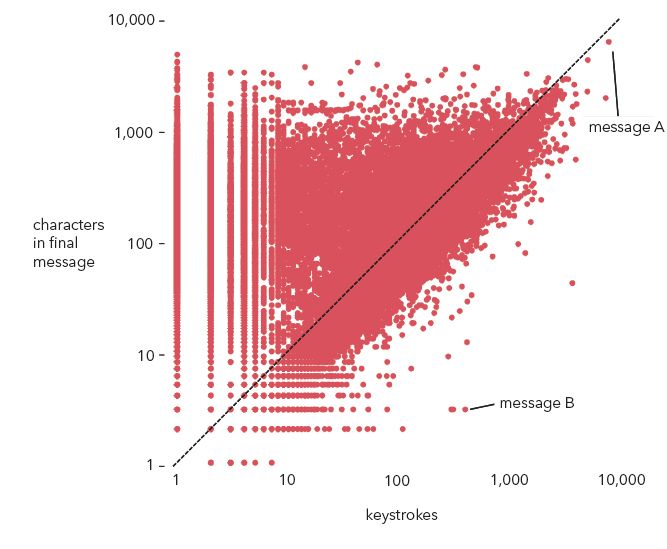

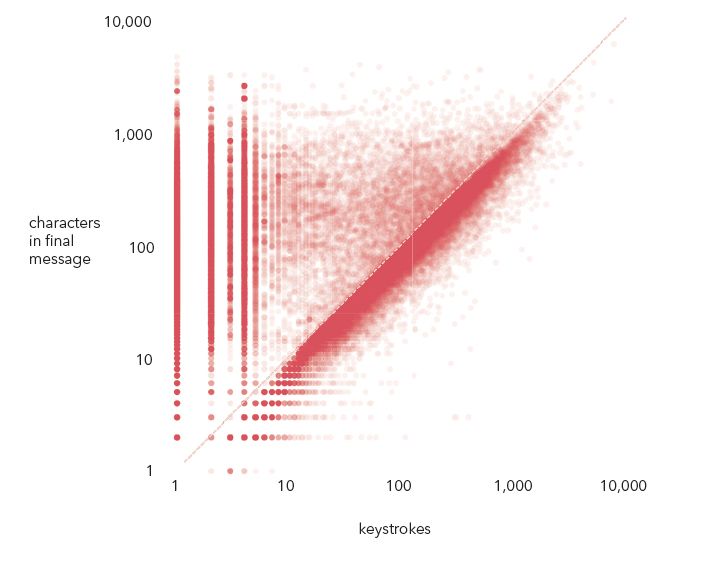

Below is a scatter chart of 100,000 messages, with the number of characters typed plotted against characters actually sent. Because there’s a wide range of counts, running from 1 all the way to almost 10,000, this plot is logarithmic, which basically just means that as you move from lower to higher on an axis, the rate at which the value increases goes up.

I’ve added a diagonal line, and it marks the place where the two axes are equal — meaning that for the red dots along it, the text matched the keystrokes that went into it. Essentially, the sender typed what was on his mind and hit Send, no backspace, no edits. Therefore we know that message A, in the upper-right corner, was typed more or less in a headlong rush, with almost no revision. Going back to the logs, I found it took the sender 73 minutes and 41 seconds to hammer out those 5,979 characters of hello — his final message was about as long as four pages in this book. He did not get a reply. Neither did the gentleman sender of B, who wins the Raymond Carver award for labor-intensive brevity. He took 387 keystrokes to get to “Hey.”

But these are the examples at the extremes. The broad gist of the scatter plot is: as you approach the diagonal, the messages show less revision. Move toward the bottom right, you get heavy editing, toward the upper left, you get … physical impossibility. Our chart’s geometry means that as soon as you cross over the diagonal into the upper half, you’re into people who must’ve typed fewer characters than their messages actually contained. Who are these arcane summoners, wringing words from thought alone? They are the cut and pasters, and they are legion. (Think about it this way: if you create a new message and hit CTRL + V — the standard shortcut for pasting on a PC — you’re only using two key strokes to paste in a message that’s probably way longer than two characters.)

We can clarify the graph by making each dot 90 percent transparent. This lets you see the real density underneath. It’s like we’re taking an X-ray of the data, and in so doing, we see the bones:

That dense band of dots running just below the diagonal is the writing-from-scratch guys. It’s surprisingly compact. There is, of course, the hard upper boundary of the line, which separates the from-scratch messages from the pasted ones, like a border between warring factions. But the band’s lower boundary is almost as crisp. There appears to be a natural limit to how much effort a person is willing to put into a message. If you do the arithmetic, it’s 3 characters typed for every 1 in the finished product.

Above the diagonal are the people who decided that kind of effort was too much. That diffusion of dots in the upper-left center is all the people who pasted a templated message and made a few edits to it. Here the logarithmic nature of the chart can fool you — even just a small amount over that central line means most of the content in the message is stock. Running up the left side, you see the dense vertical lines, the ruts. Those are the messages that were “typed” with just a few keystrokes. There are a lot of them — all told, 20 percent of the sample registered 5 or fewer keystrokes. These writers settled on something they like or that works, and they went with it.

It’s not spam in the way we normally use that word — OkCupid is quick to get fake or bot accounts off the site. These are real people’s attempts at contact, essentially memorized digital pickup lines. Many are about as lazy and mundane as you’d expect: “Hey you’re cute” or “Wanna talk?” — just digital equivalents of “Come here often?” But some of the repeated messages are so idiosyncratic it’s hard to believe they would even apply to multiple people. Here’s one, presented exactly as typed:

I’m a smoker too. I picked it up when backpacking in May. It used to be a drinking thing, but now I wake up and fuck, I want a cigarette. I sometimes wish that I worked in a Mad Men office. Have you seen the Le Corbusier exhibit at MoMA? It sounds pretty interesting. I just saw a Frank Gehry (sp?) display last week in Montreal, and how he used computer modelling to design a crazy house in Ohio.

That’s the whole message — the sender was trying to pick up women who smoked and were into art. The unstudied “(sp?)” is my favorite flourish. Forty-two different women got this same message.

Sitewide, the copy-and-paste strategy underperforms from-scratch messaging by about 25 percent, but in terms of effort-in to results-out it always wins: measuring by replies received per unit effort, it’s many times more efficient to just send everyone roughly the same thing than to compose a new message each time. I’ve told people about guys copying and pasting, and the response is usually some variation of “That’s so lame.” When I tell them that boilerplate is 75 percent as effective as something original, they’re skeptical — surely almost everyone sees through the formula. But this last message is an example of a replicated text that’s impossible to see through, and, in a fraction of the time it would’ve taken him otherwise, the sender got five replies from exactly the type of woman he was looking for. And let me tell you something. Nearly every single thing on my desk, on my person, probably in my entire home, was made in a factory alongside who knows how many copies. I just fought a crowd to pick up my lunch, which was a sandwich chosen from a wall of sandwiches. Templates work. Our social-smoking architecture-loving backpacker is just doing what people have always done: harnessing technology. In this case his innovation is using a few keyboard shortcuts to save himself some time.

As we’ve seen, phones and services like Twitter demand their own adaptations. The eternal here is that writing, like life itself, abides. It changes form, it replicates in odd ways, it finds unexpected niches … it even, like anything alive, occasionally stinks. But realize this: we are living through writing’s Cambrian explosion, not its mass extinction. Language is more varied than ever before, even if some of it is directly copied from the clipboard — variety is the preservation of an art, not a threat to it. From the high-flown language of literary fiction to the simple, even misspelled, status update, through all this writing runs a common purpose. Whether friend to friend, stranger to stranger, lover to lover, or author to reader, we use words to connect. And as long as there is a person bored, excited, enraged, transported, in love, curious, or missing his home and afraid for his future, he’ll be writing about it.

Reprinted from Dataclysm: Who We Are When We Think No One’s Looking Copyright © 2014 by Christian Rudder. Published by Crown Publishers, an imprint of Random House LLC.