The year had barely begun when Dylan Farrow published a lengthy open letter to Hollywood, slamming actors and movie fans for ignoring the sexual abuse allegations she first made against her adoptive father Woody Allen in 1993. The White House had recently released a report about sexual and domestic violence against women and girls, and announced that it was investigating sexual assault policies on college campuses across the country. The stories didn’t really seem related.

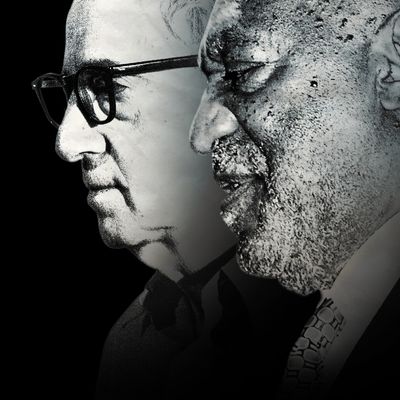

But as 2014 draws to a close, it seems like we’re right back where we started. Woody Allen has faded from the headlines only to be replaced by Bill Cosby, who has been accused of drugging and raping more than a dozen women. We’re still talking about campus sexual assault — fighting about how prevalent it really is, whom to believe, and what to do about it — in the wake of a Rolling Stone story about contested rape allegations at the University of Virginia. And every month in between then and now, sexual assault has made headlines in nearly every section of the news.

In most cases, the public was presented with two sides of the story and no definitive court ruling on the accused’s guilt or innocence. In addition to Allen and Cosby, lesser-known public figures like Canadian journalist Jian Ghomeshi, music producer Dr. Luke, and novelists Gregory Sherl and Tao Lin were pushed into the spotlight after whispered allegations of sexual violence grew too loud to ignore. The NFL fired Ray Rice after TMZ published video footage of him dragging his unconscious wife out of an elevator. A rape survivor at Columbia University carried her mattress to class every day, and California passed a law to push campuses toward policies that make it easier for accusers to come forward.

It seems wrong to declare this the year of sexual and domestic abuse. After all, these crimes have been perpetrated for millennia. Yet there has been an undeniable shift in the amount of attention paid to what were previously deemed private matters. For decades, feminist activists have insisted that abuses that occur behind closed doors should be of public concern, and it seems the rest of society is finally starting to absorb the message. Some of this probably has to do with the modern tendency to share the mundane details of our own lives on social media, where we also feel empowered to peek at and discuss the lives of others. It makes “private” crimes seem a lot less private. Traditional media outlets have also become more willing to publish the stories of survivors, even if their cases have never gone to court or have been dismissed by campus disciplinary boards. Social media then amplifies those stories and keeps them in the news. Sexual assault and domestic abuse are the sorts of crimes that test observers’ basic assumptions about who’s more likely to be telling the truth and about who holds more power: the accuser or the accused. This year, we couldn’t stop discussing them.

And so the stories keep coming. Journalists, amateur fact-checkers, and vigilante bloggers continue to dissect the Rolling Stone feature. Women in Chicago and New Delhi have charged Uber drivers with raping them. Lena Dunham is being hit with a torrent of conservative hatred because she dared to talk about a time when she was assaulted in college. “Speaking out was never about exposing the man who assaulted me,” Dunham writes. “Rather, it was about exposing my shame, letting it dry out in the sun.” Many survivors who told their stories this year weren’t seeking a criminal conviction, in fact. They sought collective accountability.

This is a distinction that’s been completely lost in almost every abuse story. Even when the accuser doesn’t reveal her attacker’s name, people on Twitter question her motives. Nationally syndicated writers sneer at her “coveted status,” especially if she is not identified by her real name. Other opinionators call for more facts before rushing to judgment, even if dozens of other women have come forward with nearly identical allegations. Cable-news commentators demand to know why she’s speaking out without pressing charges and want to know why she’s ruining some guy’s life with accusations she can’t prove. Her story is measured against statistics, usually circulated in a compelling infographic. There are hashtags (#YesAllWomen, #WhyIStayed, #IStandWithJackie) and counter-hashtags, op-eds and responses. There is usually a trial in the court of Reddit.

The upshot of all this discussion is both sad and inspiring: I think we’re making progress overall, but at the expense of individual survivors. The Ray Rice case, among others, pushed the NFL to revise its code of conduct. The White House launched its investigation of colleges’ assault policies, and California changed its sexual consent standards because the stories had grown so numerous, they were impossible to ignore. Bill Cosby will never again peddle synthetic desserts to children. For that, we have survivors to thank. Every single person who came forward and exposed what she considered to be a shameful experience, who was subjected to the court of public opinion and threatened as a result, has added to a growing volume of stories that prove, by their sheer existence, that this is a real problem.

But another lesson of 2014 is that even those of us who are inclined to believe survivors can end up undermining their stories by amplifying them. Wrote the Rolling Stone editors, “In trying to be sensitive to the unfair shame and humiliation many women feel after a sexual assault, we made a judgment” — a judgment not to fully investigate the survivor’s story, which left her open to a barrage of criticism after discrepancies in her narrative were pointed out. And what about survivors who didn’t choose to come forward at all? Janay Rice wasn’t “telling her story” when TMZ published footage of the aftermath of her assault without her consent. We all took the opportunity to discuss it anyway.

Sexual violence — a thing that women have long worried about in the back of their minds, or whispered about among themselves, or felt shame about having experienced — is no longer relegated to feminist blogs and women’s magazines. It’s part of the national conversation among sports fans and TMZ viewers and news junkies. Most of the survivors we hear from still fit a certain profile — educated, generally sympathetic women without a criminal record. There are still so many stories we don’t hear regularly — of sexual assault in prison, of rape as a war crime, of child sexual abuse, of male survivors. These and many other survivors still choose to stay silent, and I don’t blame them. But at the very least, if they’ve read the news this year, they’ll realize they aren’t alone.