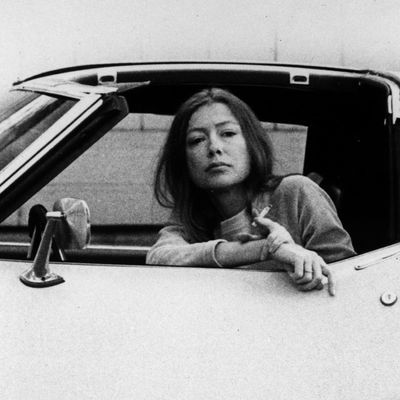

Picture Joan Didion in or near a Corvette, smoking cigarettes elegantly, drinking bourbon casually, whispering, ruefully, was anyone ever so young, and you have the 19-year-old writer’s fantasy version of herself.

As it happens, fantasy 19-year-olds are fashion’s favorite people, so it makes a certain sense to see that industry embrace Didion, too. Last week, when she appeared in an ad for Céline — sitting on a couch, dressed in black and a big pendant, her dark glasses slightly askew — Didion promptly became the object of fashion effusions. Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, and the New York Times “Style” section all compared the campaign’s online splash to that of Paper magazine’s December cover, which featured an oiled Kim Kardashian and the stated aim of “breaking the internet.” Swoon, and YES, and “my heart just stopped,” said the broken internet, of Joan. We closed the week circulating pictures of a $1,200 leather jacket with a giant Joan Didion on the back. Invoking Didion’s image is a way to confer seriousness on style, which is a gesture that easily backfires.

Worshipping Didion has always been a tricky business. If, as Didion wrote, “one of the mixed blessings of being twenty and twenty-one and even twenty-three is the conviction that nothing like this, all evidence to the contrary notwithstanding, has ever happened to anyone before,” then proudly identifying with her work falls into the same group of coming-of-age non-anomalies as loving silent city streets at dawn. Someone could write a “Goodbye to All That” about (eventually, bittersweetly) leaving the cult of Joan Didion. I say this as someone who closed her favorite college essay by pointing out that we tell ourselves stories in order to live. You emerge wistful for the schoolgirl that used to be me — the one who hoped leotards and certain rhetorical tics might elevate her own misadventures — but sturdier, happier, wiser. You can still like The White Album a lot.

Last week was not the internet’s first time loving Didion: One analysis referred to her “Tumblr currency,” which derived from something manifest in her highly re-bloggable packing list, plus all those good quotes and vintage photos. In November, a proposed Joan Didion documentary on Kickstarter (pledge $2,500 and get “JOAN’S PERSONAL SUNGLASSES”!) took in more than twice the funding it sought. But the most recent outpouring emphasized what an odd fit she’s always been as the object of mass adoration, especially online. She is idolized because she doesn’t appear to have idols. To gush over Joan Didion seems like a misreading.

Start with her eye for the details of taste. Whether locating the mid-century daughters of San Bernardino in teased hair and waltz-length wedding dresses, or the Marxist theorists of second-wave feminism in “thin raincoats on bitter nights,” Didion uses the shorthand of style to capture the vagaries of sensibility, to trap subjects in their habits and affectations. She catalogues groups by their clichés like a taxonomist. (How would Joan Didion describe the fans of Joan Didion?) Here is the opening of her 1979 essay on Woody Allen:

In the large coastal cities of the United States this summer many people wanted to be dressed in ‘real linen,’ cut by Calvin Klein to wrinkle, which implies real money. In the large coastal cities of the United States this summer many people wanted to be served the perfect vegetable terrine. It was a summer in which only have-nots wanted a cigarette or a vodka-and-tonic or a charcoal-broiled steak. It was a summer in which the more hopeful members of the society wanted roller skates, and stood in line to see Woody Allen’s Manhattan.

This is all by way of introducing Allen’s list in the movie of reasons why life is worth living (Groucho Marx, Willie Mays, Sentimental Education), a list that’s “modishly eclectic, a trace wry, definitely OK with real linen.” Allen’s list of cultural touchstones suggests to Didion “the ultimate consumer report” — a tally of unimpeachably selected products. She is mystified by “the extent to which it has been quoted approvingly.” Didion herself is a master of consumer reports; hers, though, are usually a means of dismissal. In the Manhattan essay, she’s disparaging the notion of taste as self. After all, getting smoothly reduced to a litany of lifestyle and pop-culture reference points seems like it ought to be damning, and that’s what Didion intends.

Yet these are the general terms of online existence. Even having outgrown Manhattan-ish lists of favorites, we map our tastes on the public moodboards of Tumblr, Instagram, and every dating site. We volunteer our beauty routines; we feel not unreasonable awareness of the assorted brands that constitute our own. Last week, Warby Parker, purveyor of eyeglasses, released an “Annual Report” feature that offered — as a fun and shareable advertorial service — to render users as quirky lists. This is the landscape in which we love Joan Didion for Céline. Online, it’s especially easy to believe in a transitive property of liking — that by liking something and announcing your like of it you acquire some part of its shine. Haley Mlotek wrote for the Awl about Didion and Céline, acknowledging the allure of this fantasy. “I keep my elected representatives prominently displayed on my coffee tables and bookshelves and all over my tweets,” she wrote, “as though these signifiers are supposed to tell you something really, really important about me.” Liking, listing, and sharing are how you announce a self. And Didion now has become an established talisman of taste, an ideal entry in any catalogue of preferences. Reasons life is worth living: Phoebe Philo, Joan Didion.

Part of the problem here is that she made her own taste look so good. Not that she’d deign to list them, but enthusiasms of ‘60s- and ‘70s-era Didion (arguably prime Joan for cultists) include jasmine, the Doors, and large-scale desert waterworks, which sound like the makings of a very stylish Instagram. She doesn’t admit messy passions, the kind that might go bad. Those, when they appear, tend to be past tense — New York through the eyes of a 20-year-old, say — and so more neatly dissected. She fuses impeccable taste with apparent self-exposure and inspires followers to try for the same.

But what a beautiful, magical miracle it would be if anyone could manage to look this good online! Imagine Joan Didion with a defunct MySpace page, Joan Didion in Storified arguments with Pauline Kael! No wonder we covet not just her stuff and her skill, but her life. All those stories of unhappiness and social discomfort happen at a distance — they’re confession from its best angle. Vulnerability, in the context of Joan Didion, means extreme thinness and a carefully described migraine. Vulnerability, for a contemporary would-be Didion, means the detritus — the abandoned poses, changed opinions, and tweeted epiphanies — that we leave behind us all the time. In a recent interview, Meghan Daum mourned the biodegradability of newsprint. “When we write on the web, it’s Styrofoam,” she said. “It’s disposable; you don’t need it after five minutes, and yet it’s never going to go away.” You can still try to reveal yourself in the Didion mode, with lean prose and poetic idiosyncrasies — but the chances are good there’s plenty of intimate, strange, indestructible material trailing in your wake already.

In “On Keeping a Notebook,” Didion advises staying “on nodding terms with the people we used to be.” This presumes that past selves — with all their feelings and pretensions — are people who readily disappear. Here, to steal a Didion tic, is what I want to tell you: No one now young will look as cool at 80 as Joan Didion.