Goga Ashkenazi has a friend coming through Milan in a day, so she decides to have some people over—a small dinner for 12, she figures, though, by the morning of, it’s turned into a big dinner for 100 with a band and a DJ.

Around 6 p.m., on her way out of the office, her personal assistant, José, pokes his head in to tell Goga her driver’s downstairs.

“How does the house look?” she asks.

“Okay, I think,” José says. “Actually, gorgeous.”

“Can you get someone to come do my hair?” Goga asks. “Extensions are falling out.”

Goga’s a long-limbed and flirtatious woman of 35 with 32 years of experience in hoping to someday become a dressmaker. During that time, she has witnessed a number of remarkable moments (such as the fall of communism, which happened when she was growing up in the Soviet empire) and scored many accomplishments of her own, including a degree at Oxford and the establishment of an oil-and-gas company in her ancestral homeland of Kazakhstan that earned her a fortune and made her one of the country’s first female oligarchs. She is also famous for her high-end run of male companions, which has included Prince Andrew of Great Britain, Lapo Elkann (the Fiat heir and the closest thing to a reigning Italian prince), and Saif Qaddafi (a son of the late Libyan dictator). Her proudest moments were giving birth to two sons via what she calls her “close friendship” with Timur Kulibayev, a Kazakh oil billionaire in his own right and, for two decades and counting, the son-in-law of the country’s president. “It’s complicated,” Goga says.

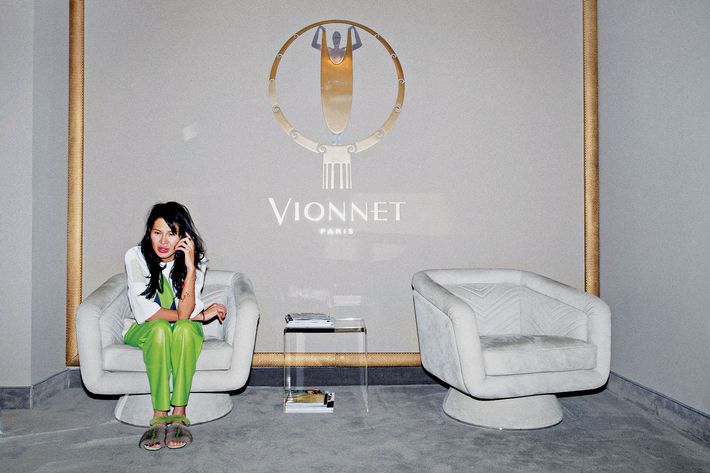

Despite all that, it wasn’t until 2012, when she bought the historic fashion house Vionnet and installed herself as the chief designer, that she felt she’d begun to find her place in the world. “Goga has a very can-do-it attitude,” says her friend Gianluca Longo, a stylist in London. “She loves clothes, so she buys a famous old company. It’s like, if you like spaghetti, you decide to buy Barilla.”

“My old life wasn’t me,” Goga says. “I kind of had a moment. Almost immediately, I sold my energy company. I realized I wanted creative. To me, fashion is art.” Growing up in Moscow, where her father served in Mikhail Gorbachev’s Central Committee, Goga lived for clothes. Even though all the girls at her school were required to wear brown jumpers, she persuaded the seamstresses working on the ground floor of her apartment building to perform some custom tailoring. “I had navy, green, Bordeaux,” she says. “They made me macramé, lace. I saved every issue of Burda Moden—the German magazine with patterns that they allowed us to get. Then, the Vogues got passed around. Diplomats brought them back.”

For ten months preceding the acquisition, she holed up in Florence—less a hole, really, and more a 28-room villa on 80 hectares with an adjoining ten-room guesthouse, frescoes by Michelangelo, and a smashing view of the Duomo. “In the morning, the tutors came,” she says. “I studied history of art from nine to 12 and then, in the afternoon, outside activities: painting en plein air, or we went to museums.”

“It was a very nourishing era in her life,” says Goga’s good friend Eva Cavalli, the onetime Miss Universe finalist who is married to the designer Roberto Cavalli and served as her unofficial adviser during this transitional phase. “She had parties that lasted for days—murder-mystery weekend, truffle hunting—and we talked about finding the right label to purchase.”

Goga considered Ferre. “Bit of a problem,” she recalls. “Owners didn’t put money in like they were supposed to. It was three, four years away from being ready.”

Also, Ungaro, though here she was too late. “By then the owner had sold the beautiful boutique on Avenue Montaigne and the licensing business,” Goga says. “So maybe it was better not to have.” (This was also a few years after Lindsay Lohan was given the reins to design her own line, to disastrous effect.)

Then along came Vionnet, an aristocratic French house that had been dormant from 1939 until 2006, when a series of investors struggled to revive it and moved its headquarters to Milan. “When I heard Vionnet was looking, I jumped on the plane that day and by afternoon I signed the memorandum of understanding,” Goga says. “I would have paid three times as much as they asked.”

But not everybody sees her reinvention project as something the world needs. A columnist in the Financial Times likened her to Roman Abramovich, the Russian billionaire whose hobbyist ventures include ownership of an English Premier League soccer team. “I’m sensitive to what people think of me, because, I admit it, I was tacky at first,” she says, adding that she has learned new things every day. “I’ve been studying with the sartori, the tailors. I know the names of hems in Italian.” The people of Milan, she goes on, “have been very welcoming to me.”

Throwing a good party, like the one on this November night, is a form of reciprocation. Goga lives in a four-story palazzo just off Montenapoleone, Milan’s grand boulevard of high retail. It’s one of the biggest mansions on a block famous for its late-Renaissance architecture, with a winding Gio Ponti staircase and a swimming pool out back. She’s renting (property taxes for foreigners are brutal) from an elderly marquesa who inhabits an apartment on the top floor. “She’s adorable,” Goga says. “She gets excited when I tell her I’m doing a photo shoot here.”

Goga has on black Capri pants, tall boots, and a halter top that looks like an umpire’s chest protector, except that it’s 100 percent mink fur and has a mint-green stripe running up the middle. It’s around 11 p.m. when the guest of honor arrives: Olivier Zahm, the editor of Purple, a Parisian fashion magazine with a lot of nudity. He wears a motorcycle jacket, aviator sunglasses, and a baseball cap.

“I have to show you something,” Goga shouts to him and pulls aside the edge of her top so that he can see she recently got her nipple pierced.

“Superbe,” Zahm says, extending his hand for a high five.

“Everybody, this is Olivier,” she calls out to the dining-room buffet, where people have started lining up for risotto. “Olivier, this is everybody.” She leads him onto the dance floor, throwing shapes to the dueling bongo drums played by Giacomo and Franco Loro Piana, scions of the family that until recently owned the eponymous clothing line. Zahm manages to swivel his hips along with hers while keeping one hand in his pocket and, with the other, taking photographs of himself beside every pretty girl who walks by.

“Go, Loro Piana boys! Go!” Goga shouts. “Who knew?”

Goga arrives at Vionnet headquarters—another ancient palazzo a short walk from her house—in a neoprene Vionnet sweatshirt of her own design, with quilted shoulders and leather sleeves. She is five-ten, with coffee-colored eyes and cheekbones as high and broad as the Tatar plains. The nails of one hand are painted light blue, and the other hand’s are the color of blood; the back of her neck bears the tattoo of a zipper. Her desk is a large slab of lacquered maple, with marquetry in a sunburst pattern. On a nearby wall is a thumbtacked arrangement of drawings and photographs—her inspiration board for Vionnet’s 2015 “pre-fall” collection, the theme of which, Goga has determined, will be “contrasting realities.”

“I haven’t done all of the philosophy yet, but the conceptual point is beauty and decay, naked but dressed, wise children, fake but real,” she says. “Also, limited freedom: plissé but the body is free; plissé but unruly. The plissé is one of our signatures. I wrote down ‘echo of one’s own universe.’ I went a bit too deep.”

The inspiration for the inspiration board came from the trip she and her creative team took in October to Iceland and Greenland: “You know, fire and ice? The sun is setting, and the full moon’s coming up. Four of us flew by helicopter over a volcano, where the lava was hitting the icebergs. We got on the front page in Iceland. Apparently, you’re not supposed to land there when the volcano’s active. I think that everybody wants to, but not everybody can.” She’s especially proud of a video she made on her phone with slo-mo footage of herself leaping along the geothermal coastline set to Pacha Ibiza music by Fedde Le Grand.

She was born Gaukhar Berkalieva. Her surname came via a brief marriage to Stefan Ashkenazy, the heir to a Southern California real-estate fortune. (“The Russians spelled it wrong on my passport, so I went with it and kept the i at the end,” she says.) Even though her father had a Muslim background and her parents, as Communists, professed atheism, Goga’s maternal grandmother was Jewish, and she carries a page from a 1,200-year-old Torah in her purse. “So I didn’t have to convert for my wedding,” she says. “I asked the nine questions.” She adds that West Hollywood was a tough environment for her as a new bride. “I hated the conversations: ‘Come to this party—Phoebe from Friends is going to be there.’ ”

She has always considered herself “the big outsider,” she says. “In Moscow, they could tell by looking at me that I’m not Russian, but I don’t even speak Kazakh—I blame my parents.”

She rhapsodizes about her privileged life as one of the ruling party’s elite in pre-glasnost Eastern Europe. “There was more to communism than people realize,” she says. “We lived very well. I thought everybody did. Our building was all officials and their families—so much fun. We went to weekends in the country, a compound with horses and hunting. All the camps were given out to different ministries according to your status.”

And life got even better after the fall. “In 1991, my father was able to use his connections to privatize a factory in Kazakhstan, so suddenly we were wealthy. Within a year, my mother sat me down and said, ‘The world has changed. We’re in a position to give you the best education in the world. You’re going to be competing with the most privileged children in the world.’ I was 12. I said, ‘Mommy, I’d love to do it.’ ” She was sent to a series of English boarding schools—“rusticated” (i.e., suspended) from Stowe for having a boy in her room, then graduated from Rugby, where she learned to eat Marmite. “We used to eat this many toasts,” she says, indicating a stack with her thumb and forefinger.

Oxford was great fun, and so were weekends in London—hence the “third-class honours” notation on her degree. She held a few investment-banking jobs in the City and in Hong Kong, then at 24 partnered with her family in Kazakhstan to start MuniaGaz Engineering Group, which builds compressor stations for oil and gas pipelines and made her rich almost overnight.

“People say I was in the oil business, but I was never drilling wells,” she says. “We were a construction company. I was also in gold mines. I still have minority interest in all of it, but I’m no longer running them.”

The press in Central Europe and London, where Goga owns a £28 million mansion in Holland Park with a household staff of 15, has shown obsessive tendencies regarding her romantic life. A few years ago, when Prince Andrew was pressured to stand down from his post as the British special representative for international trade because of a host of shady-looking friendships, she came to his rescue perhaps a bit too eagerly, bragging how he’d confided in her. She was also credited with enabling a sweetheart deal when the Duke of York, who’d been struggling to sell his £15 million country manor, suddenly sold it for £18 million to her boyfriend, Timur Kulibayev. One columnist compared her to a Bond girl.

There were also questions about her on-and-off union with Kulibayev, which began in 2005. Kulibayev, who resides in Kazakhstan, remains married to the daughter of President Nursultan Nazarbayev and, at 48, is widely considered a leading candidate to replace him. According to a U.S.-embassy cable released by WikiLeaks, Kulibayev is “the ultimate controller of 90 percent of the economy of Kazakhstan.” A documentary critical of Goga’s oil and gas ventures, produced by a TV station in neighboring Kyrgyzstan, was titled The Princess and the Poor. Global Witness, an international think tank, calls Kazakhstan a “ ‘kleptocracy’ run by and for the benefit of the ruling family and its close associates.” Goga says most of the harsh assessments of her, including the documentary, come from a wealthy faction within the government’s opposition party. “It’s all political,” she says. “That’s what I ran away from.”

Goga and Kulibayev’s boys, Adam, 7, and Alan, 3, are full-time residents of London, where they are cared for by her mother. “I fly back any weekend I can, but my career is in Milan,” Goga says. “I never gave my children a normal family. Their father and I, we both wanted them to grow up in England—the values, the manners, the academics. But neither of us were ever going to—we both travel so much. We were watching a cartoon with a normal family with a mommy and daddy at home, and Adam said, ‘Look, his parents have already come to visit him!’ It was sad, but I thought: Is he suffering? My mother is No. 1 for them. She’s obsessed.” Each boy also has two nannies, one Russian and one English.

Her parents—still married, though her father spends most of his time in Kazakhstan—never questioned her design for living, and in a sense she holds her mother responsible for her independence. “I remember my mother sitting in the lotus position in our living room with Mozart on,” Goga recalls. “We were not to disturb her during yoga. When I was 8, I found myself an English tutor on the phone. I went four years. My mother never saw her once.”

To the side of Goga’s desk is a drawing Adam did titled Mommy in Space of the planet Earth floating against a sky. The British Isles are situated disproportionately far from Italy, but near Milan is the Vionnet logo—a Deco-era sketch of a woman’s figure as she pulls a gown over her shoulders—and the words GOGA MAKES THE BEST DRESSES.

Clothes only account for part of Goga’s workload. A lot of what she’s trying to do involves ingratiating herself with Milan’s haute-bourgeois, and often insular, fashion world, a mission that plays to her strengths. At dinner one night, she’s quick to identify her friend Vincenzo Viscione as a member of “one of the best families in Italy.” Another day at work, she charmingly teases Giorgio Finzi, a handsome 26-year-old come to seek Vionnet’s involvement in a start-up e-commerce site, about all the models he must have dated. When he finishes his pitch, Goga says, “Let me speak to my board of directors,” pretends to look under her desk for a split second, then exclaims, “Okay! Honey, you had me at ‘Hello.’ ” It probably says as much about Milan as it does about Goga that they met when Finzi was working for his mother, who did some public relations for LVMH: “I was working in Mommy’s office before I started this,” he says. He also turns out to be a descendant of the family on which In the Garden of the Finzi-Continis is based.

Goga groans when Finzi says the site will also sell Phillip Plein clothes. The krautrock-style label is booming. “He’s the opposite of what Vionnet is about,” she says.

“He’s a big partier but very successful,” Finzi says. “Chapeaux, chapeaux—hats off.”

“Chapeaux,” she concedes.

Goga thinks it’s essential to reestablish Vionnet’s connection to its own gilded history. The label was founded in 1912 on Paris’s Rue de Rivoli by Madeleine Vionnet, folded at the outset of World War II, and then was largely forgotten. Goga is constantly hosting documentary filmmakers, fashion historians, and editors of niche magazines—none of them too small for her to take a meeting with in the hope that their cooperation will more swiftly “shape the legacy,” as she puts it, of the label. She is sponsoring a prize at Central St. Martin’s, in part so that students might devote more research to Vionnet, and she is intent on collecting an archive of every item the house has made. “Madame Vionnet donated her personal collection to the Louvre, but the rest is spread all over the world,” she says. “The museum keeps her dresses like the Mona Lisa, in bags without air so they don’t disintegrate. They bring them out like dead bodies on trolleys.”

Madame Vionnet was known as the architect of designers. She invented the bias cut. “Before her, you saw no body,” Goga says. “Women’s dresses were all corsets and layers. But when she turned the material diagonally, it made the thread turn. It frames the body. The salesgirls refused to sell her collections—it was so sexy!” Bruce Chatwin once wrote that Madame Vionnet “insisted that women remain women when other couturiers would have their clients resemble boys or machines.” Vionnet herself chose not to embody the look she invented. “I have never cared to dress myself well,” she told Chatwin in 1973. “I was short … and I hate short women!” She generally lived a quiet life, avoiding restaurants and attending the theater alone. “I was never mondaine,” she said.

When Goga took the helm in May 2012, she thought she might ease her way into Madame Vionnet’s mantle. “I didn’t expect to have creative direction right away, God forbid,” she says. But there was an immediate tear in the organizational organza when she met with the chief sitting designers, the twins Barbara and Lucia Croce. “They were lovely, lovely, lovely people, but they came from Prada and they were doing basically very boxy silhouettes, very grown-up color palette,” Goga recalls. “I went to the showroom, and I was in shock. I thought, This is not my woman. I said, ‘Girls, how about we get us a stylist?’ They were like, ‘La, la, la.’ ” The relationship disintegrated, and by July, shortly before the presentation shows in Paris, the Croces were gone.

The stylist Goga found, George Cortina, had worked previously with Chanel and Gucci. “And when he looked at what we had, he said, ‘Goga, this is shit, shit, shit, shit, shit,’ ” she says, pointing her finger left and right to imitate. “But he said, ‘‘Don’t do anything crazy, because the world wants to kill you, this nouveau riche girl that’s here to play fashion.’ I didn’t want to come out to Paris. During the show, I did like this, for one second.” She bobs her head forward from behind an imaginary curtain.

The first show is remembered as a disaster nonetheless—not for the clothes, but because Goga insisted on staging it as a black-tie dinner at the Hôtel Salomon de Rothschild and kitting it out with flowers, crystal, the whole czar’s boudoir. (“It was like the Sputnik had landed,” one friend of hers jokes.) Franca Sozzani, the editor of Vogue Italia, stood up and left. “I told her it was not the way to do things and that I think sometimes you have to go a little bit more on toe-tips,” Eva Cavalli says, stressing that Vionnet has become “more sophisticated” in the years since. “She ignored so much of my advice, but that is Goga: no hesitation. She took some risks. She took some slaps in the face.”

Albino D’Amato, a designer whom Goga brought on six months into her tenure, describes Vionnet’s place in the market in the years before Goga’s arrival as “more first-degree commercial.” Now, he says, “it’s more conceptual, more elemental, a more intellectual price point.” Vionnet day dresses run from around $800 to $1,350, and evening gowns start at $2,000 (though hand-embroidered pieces can cost in excess of $5,000, and sable coats go for $80,000). Before Goga took over, Vionnet clothes were sold almost entirely in Western Europe, but the company says that Russia and the Middle East now make up 40 percent of Vionnet’s market, the rest of Europe about half of that, America 15 percent, and East Asia 25 percent and growing. There are currently Vionnet boutiques in Milan and Bucharest, with others set to open in Paris come fall and New York some time after that.

Goga has at times contracted out to the wisdom and taste of veterans. She hired Hussein Chalayan (who has twice won the British Designer of the Year Award) to do two of the 2014 lines, and the stylist and former editor of French Vogue Carine Roitfeld worked to make Vionnet a fixture of Hollywood red carpets (Amy Adams, Cameron Diaz, and Claire Danes have worn Goga’s dresses recently). “Goga Ashkenazi has made headway at Vionnet since her debut effort,” Style.com wrote of her fall ready-to-wear line early in 2013, pronouncing it “more runway worthy than what she did back in September.”

It helps if you can read between the lines a bit when you inquire among the fashion set about Goga. Ennio Capasa, the founder of Costume National, says he’d prefer not to discuss her, “as I feel that it would confound the idea about our two companies and our friendship.” Chalayan calls Goga “refreshing and endearing—particularly the fact that she is actually designing, unlike a lot of the people with well-known houses named after them who are essentially businessmen.” He praises Goga for being “very aware of her limitations” and says of her sensibility that “she wears clothes very well, and she understands the woman she’s designing for.”

Even when she’s hired important designers, Goga has tended not to ignore her own instincts. In 2013, she brought on Angelos Bratis, who has his own clothing label and is regarded by many as the second coming of Madame Vionnet herself—with a penchant for handkerchief dresses and “incredible draping skills,” in the words of Sciascia Gambaccini, the fashion editor of Italian Vanity Fair. But the two lines he created for Vionnet were viewed as largely constrained or overpowered by her impulses, such as when she attached fins, belts, and multitiered collars of canary-yellow kidassia goat fur to a number of streamlined pieces from their ready-to-wear collaboration. Bratis says of Goga, “She’s daring, she’s curious, she’s an amazing person.” But he is hesitant to validate her taste. “I don’t judge other designers’ work,” he says. “Of course, I love Vionnet anyway, for the history.”

In any case, there’s only room for one prize sable in the stable, and Goga came to the conclusion that she’d prefer to oversee a team of young, lesser-known designers. “Hussein’s a genius, but the clothes he did for us didn’t sell a bit,” she says. “None of the celebrities wore it, either. I looked at other big-name designers to come here, but they are such big egos. I don’t want them to overpower Vionnet.”

The morning after her party, Goga has her assistant move her appointments to the afternoon. Around lunchtime, a man in jeans and desert boots enters her office, plops down on a chrome-tubed club chair, and wordlessly opens his laptop. “Hey,” Goga says. It’s Dylan Don, a German photographer whom she calls “my best friend” and who “for a while” has been living at her house. “We sometimes fall asleep in the same bed, but nothing ever happens,” she says later. “In terms of relationships, I have serious relationships and less serious. I’m against forcing yourself into something if that becomes a burden.”

Dylan has just shot Vionnet’s spring ad campaign, featuring the Finnish supermodel Suvi Koponen, in Morocco: sand dunes, white gowns, a large wind machine. Goga sits in his lap as the two review the images on his computer to determine what needs retouching. “Get rid of cameltoe,” he suggests, and “stretch her legs and make them look longer.” He also recommends taking in the model’s arms and rear end in one shot.

“If this is fat, what is my ass?” Goga asks, not waiting for an answer. “Tell them not to polish the skin too much—it looks unnatural.”

When it’s time to have a look at some early knitwear prototypes for Vionnet’s fall commercial line, she heads down the hallway to a brightly lit atelier. A tall and freckled young model named Anastasia emerges from behind a cardboard screen in a fuzzy navy catsuit of Goga’s design. “For a certain body, like me, it looks very comfortable,” Goga says. The material is fake Persian lamb, or what the Italians call astrakhan. “My first season, I made dresses with fur. It was a lot for people to take in at the beginning. This year, I’m using a lot of fake fur—fake angora, fake castoro. It’s part of my whole ‘false realities’ thing.”

The next ensemble the model tries on is of the same fabric but in two pieces. The pants have bell-bottoms, and the top has a wide black collar. “I think we should do it,” Goga says, pressing her hand to the model’s back. “It’s perfect. And they love the touch, the Russians do, soft things like this.” She has the girls in the workroom pin notes to the shoulder straps and measure the plunge of the back.

“It’s too open here,” Goga says of the space at the bottom of the armhole. “Women don’t like to bare that part, because it’s not the most beautiful part of the body. So we fix that. It means more sales. I learned that from my team. I’m always happy to go more outrageous, lower cut to the back, one or two margins more expensive. They’re always correcting me.”

Goga brings out samples of material she’s commissioned to make dresses and coats for next year’s collections. “It’s real fur made to look like fake fur—shaved it, dyed it, cut it,” she says. She wants to do a trench coat in baby-blue astrakhan. “And a men’s-style mink coat in a Prince of Wales intarsia pattern, where the plaid is formed by stitching together stripes of dyed fur. You see: red mink, blue mink, black mink, white mink. Or we do a Scottish check in black mink, blue beaver tail, and green fox fur. How cool is this?”

Later, she is running back to her desk because she needs to catch a flight to London (it’s a private jet, but she wants to leave in time to get a landing slot at the military base near Kensington). She’s heading to Elisabeth Murdoch’s country house “for a girls’ weekend, with lots of drinking wine, I think,” and she asks her assistant to procure a house gift: “conservative, so not acid green, but not blah either,” she says. “Handbag could be fine.” But first Goga wants to watch a video clip of Marina Abramovic’s performance piece at MoMA, in which the artist’s former partner Uwe Laysiepen shows up and the two wordlessly stare into each other’s eyes for a few minutes.

“This stuff takes my breath away every time,” she says, reaching for a roll of toilet paper behind her computer and wiping her eyes. And suddenly she’s talking about her art collection: Warhols, a Basquiat, Marc Quinn flower paintings. Once, at a charity auction, she accidentally bid nearly $400,000 on a Richard Hambleton painting by waving at Jennifer Lopez.

But a piece she especially cherishes, she says, is a pink neon sculpture by Tracey Emin** that hangs in her living room in Milan, spelling out the words NOT SO DIFFICULT TO UNDERSTAND. “Do you love that or what?” Goga says. “That really is me.”

*This article appears in the February 9, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.

**This article has been updated to show the correct spelling of Tracey Emin’s name.