In a business where you’re only as good as your last collection, Marc Jacobs will always be remembered for one moment: the night he did grunge. It was November 3, 1992, in the elegant showroom of Perry Ellis, the lights of Seventh Avenue twinkling through the tall windows on the assembly of editors and buyers. Although Jacobs could hardly have known it, this was the show that would define him as an edgy, youth-minded designer. Up to then, he had been all false starts. Brought in four years earlier, at age 25, to restore Perry Ellis’s offbeat sportswear look, Jacobs had largely failed to please anyone — least of all himself. On that night, though, he was never more certain of what he wanted, and what he thought was beautiful and cool. But as Christy Turlington, Naomi Campbell, and the other supers stomped out to the clang of L7’s “Pretend We’re Dead,” in Doc Marten boots and Converse sneakers, with knitted caps and granny dresses and dingy plaid shirts layered over striped knits and cartoon T-shirts, it looked as if Jacobs had not designed any new clothes so much as raided every thrift shop from here to Seattle. As far as the reviews were concerned, Jacobs was dead. Within a few months, Perry Ellis let him go and shut down the line.

When I look back on that night, I am struck by an altogether different thought: Why were those of us in attendance such a miserable chorus of condemners? Scorn filled the newspapers over the subsequent weeks (evidently some editors still sent their copy by Pony Express). “The slaves to fashion who are sucker enough to fall for this grunge garbage deserve the slobby sartorial look they pay for,” huffed Trish Donnelly in the San Francisco Chronicle. A reporter from Seattle, the original rat hole of grunge, the term apparently first used in 1988 by a local record label, mocked Jacobs for never having visited Seattle and then, attending to her fashion-writer chores, told readers to ditch their shoulder pads. Meanwhile, in Milan, Suzy Menkes, the critic at the International Herald Tribune, handed out “Grunge is Ghastly” pins she had made up. Even the kids in Seattle threatened to wash their hair in protest of having their look co-opted by a gang of gorgeous supermodels.

More than 20 years on, I find myself questioning my own reaction to the show, the violet-scented peevishness of my tone. Writing in the Washington Post, I complained about its “lack of credibility” while tutting, “Rarely has slovenliness looked so self-conscious, or commanded so high a price.” I ignored, if I even considered, the charm and sweetness of the attitude — an attitude, by the way, which I happily embraced in my own brand of slob appeal.

The only thing that I can find wrong, now, with his effort is its timing. As the writer Rick Marin has observed, the Pacific Northwest sound and thrift-shop scene was already losing its subversive bite, thanks to MTV and Cameron Crowe’s romantic comedy Singles, released in September 1992. I don’t think Jacobs necessarily worried that his collection wasn’t on the absolute cutting edge. There was, after all, an equally compelling aesthetic of naturalness emerging from London, chiefly in the stark photographs of Corinne Day. Besides, Seventh Avenue might be geographically central in New York, but it was of a dowdy disposition, its mind set firmly with department store giants like Liz Claiborne, as well as, of course, those uptown lords of the ladies, Bill Blass and Oscar de la Renta. It needed a good slap. Still, I can sort of see how Jacobs’s plaid shirts and fuzzy caps smelled less like teen spirit than a packaged deal.

But why did so many critics allow no room on the American runways for a look that was legitimately an expression of impertinent new values — about alternative beauty, unaffected glamour, anti-luxury? Weren’t we always egging designers to make clothes that reflected their times? Instead, we slipped on our white gloves and hairnets, and sent Jacobs to bed without his supper. When Perry Ellis parted ways with Jacobs and his business partner, Robert Duffy, the company told them that it wanted to discontinue its women’s collection line, which was never profitable (few top lines are), and focus on licensed products. Taking their severance pay, Jacobs and Duffy sat out the next year. And very prudently, they put some of the Ellis money into a lease for a space on Mercer Street — the future Marc Jacobs flagship.

Although I didn’t think about it at the time, the grunge show had a precedent in outrage: Yves Saint Laurent’s 1971 haute couture collection inspired by the vintage clothes worn by his female friends. It set off a howl among editors, who complained that the show evoked still-fresh memories of women in Paris during World War II. “I think it was Hebe Dorsey who said the models looked like hookers,” Jacobs said on Monday. In fact, Saint Laurent was signaling the new and growing influence of the street. “Women were saying, ‘We don’t want to look like a Dior mannequin. We want to look funky,’” Jacobs said, adding, “It’s a very specific and special group that understands the vocabulary, the irony, the perversity, and the content of it. So, it’s almost by definition not something that most people should see.”

The same could be said of John Galliano’s controversial hobo show for Dior. Staged almost a decade after the grunge fiasco, it was inspired by the homeless people Galliano saw along the Seine and, as well, by the tramp ideal of Charlie Chaplin and the damaged souls loved by Tennessee Williams. The Dior show ignited even more outrage, with editorial writers accusing the house of exploiting the homeless and mentally ill. Yet while people were attacking Galliano on the grounds of apparent bad taste — a charge often lobbed against artists — I don’t think they considered the possibility that maybe Galliano saw something that others did not see, something exquisite and human. Almost punitively, they were telling talented designers to stay in their dressmaker box and design another bow.

Both Jacobs and the fashion historian Valerie Steele, who is the director of the Museum at F.I.T, see a parallel not only among these three shows but also between visual artists — from Cocteau to Arbus to Koons — whose work involves the morbid, ugly, or banal. “People react differently when fashion designers do that, but I think it is a very comparable thing,” said Steele. Unfortunately, only a handful of designers have the imagination (and the liberty) to make those kinds of associations.

For Jacobs, the grunge show satisfied a number of purposes. After two years at Perry Ellis second-guessing himself — not to mention the tastes of company executives and store buyers — he’d had enough. “I said, ‘Fuck it, I can’t do this anymore,’” he recalled. “I needed to do things that meant something to me.” He had a breakthrough the season before grunge with a stylish collection inspired by footage he had seen of a 1968 group concert in London with the Rolling Stones (later the basis for the documentary Rock and Roll Circus).

Jacobs remembered: “I was so pleased with that show, and because it did get a lot of attention and it did look younger and fresher, I said, ‘I’m going to do what I feel is right.’ And that’s how grunge started. I joked about it at the time but I had designing diarrhea. I just couldn’t stop. The ideas came from everywhere — whether it was Corinne’s pictures, or David Sims’s, or Juergen Teller’s. Or meeting Helena Christensen for the first time and seeing her in a shawl over a nightgown with a pair of Birkenstocks. Or it was my friend Ellen running around in pajamas and Converse with a bra. I was, like, oh my God, this is all pointing to the same thing.”

By the mid-’90s, other designers, notably Miuccia Prada, were questioning notions of beauty in new and unsettling ways; and going without makeup fit with the decade’s minimalist fashion. But at the time, Jacobs thinks now, and in the environment of Seventh Avenue, grunge exposed fear. That was the main reason, he said, people turned the show into a punching bag.

“I’ll use Kate Moss as an example,” he said. “A woman buying designer clothes can’t go to a store and put on a slip with Converse sneakers, and have dirty hair and no makeup. A woman of a certain fashion education can’t achieve Kate’s look. It went against everything that one could aspire to. I mean, you could go to a beauty parlor and look like Joan Collins. Or you could say, ‘I want to look like Cindy Crawford or have my hair cut like Linda Evangelista.’ But you couldn’t go into a shop and say, ‘I want a child’s Victorian dress that looks torn.’ I think that’s where the fear comes from.”

I think it’s safe to say that it also comes from new things, of which fashion writers are oddly intemperate. “It’s always so easy to look at the next thing and be part of the past thing,” said Jacobs, “and say, ‘That doesn’t work. It doesn’t tick our boxes.”

In the end, of course, Jacobs went on to Louis Vuitton, fulfilling the prediction of at least one editor, Carrie Donovan, in 1988, that “one of these days he will explode into the big time.” That day came, more or less, in 1997, when Bernard Arnault hired him. As for the grunge collection, it became a point of reference for future designers and critics, instantly conferring a sense of cool and, for some, bringing them back to a time in fashion when people still seriously discussed matters like taste.

And sentimental as it may seem, grunge remains his favorite collection. “Totally, absolutely,” Jacobs said. “Because it was the most liberating. And I know this can sound really corny and falsely humble, but when I trust my own instincts and when I’m actually into something — it doesn’t mean people will like it or we’ll sell it — I will sleep better at night.”

Perry Ellis Grunge Collection

Christy Turlington walks the runway.

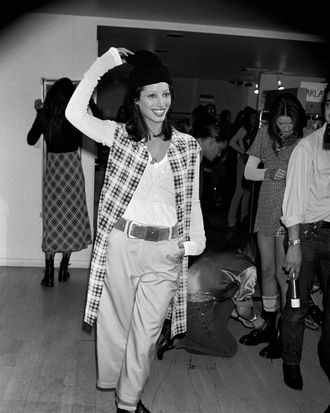

Perry Ellis Grunge Collection

Kate Moss walks the runway.

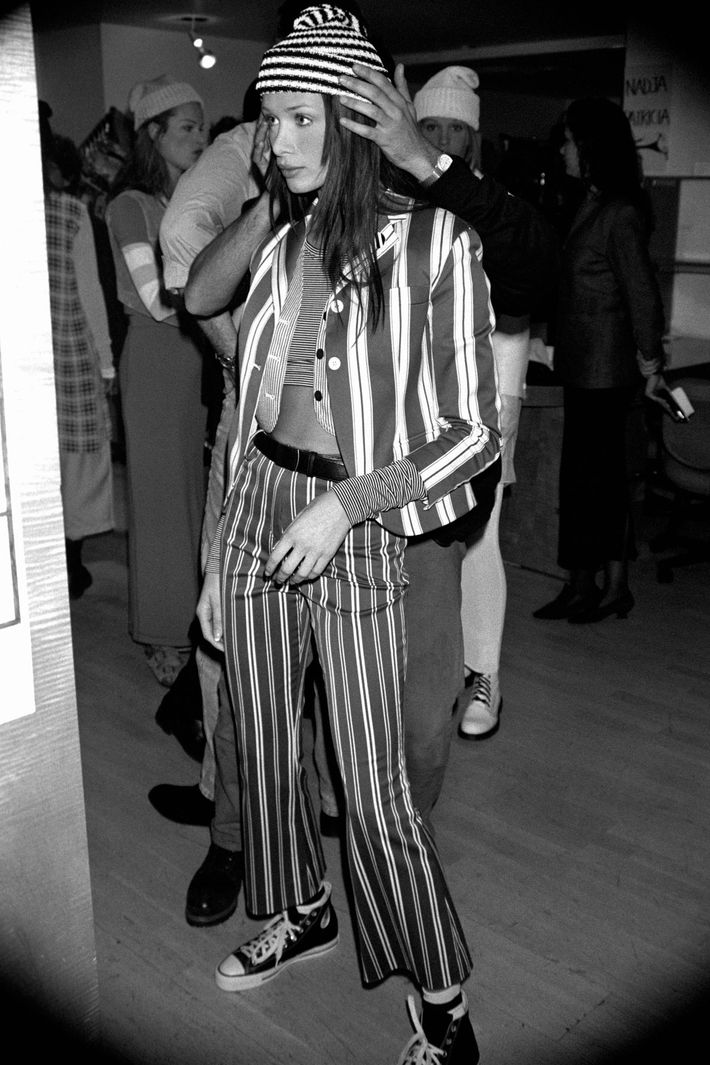

Perry Ellis Grunge Collection

Carla Bruni gets dressed backstage.

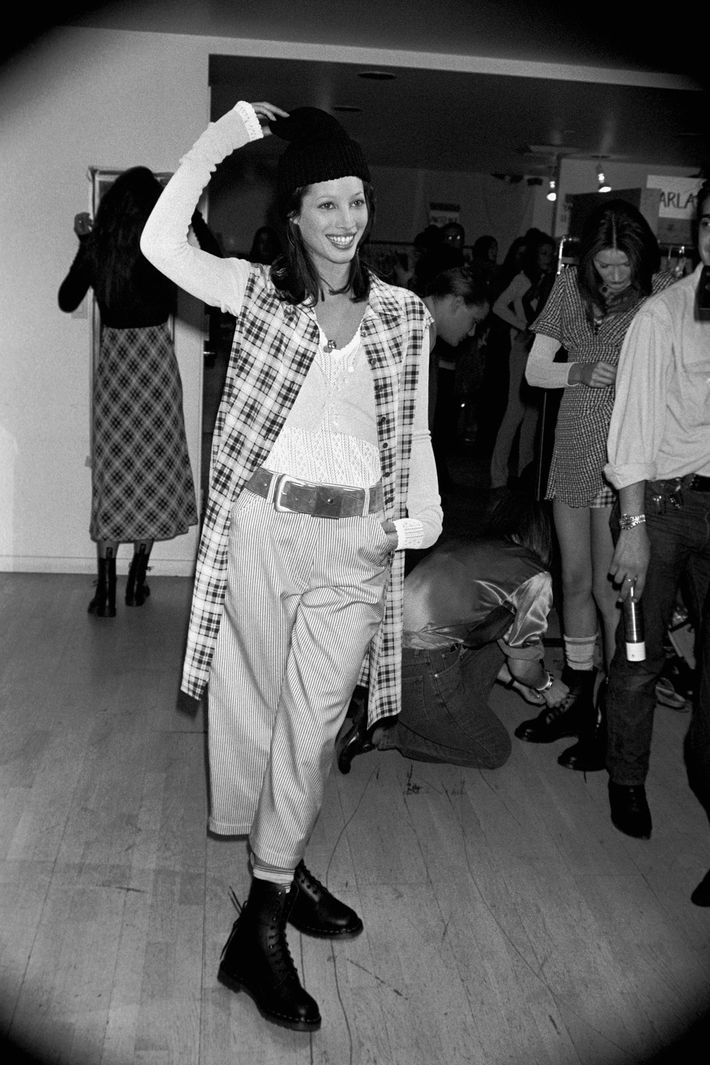

Perry Ellis Grunge Collection

Turlington backstage.

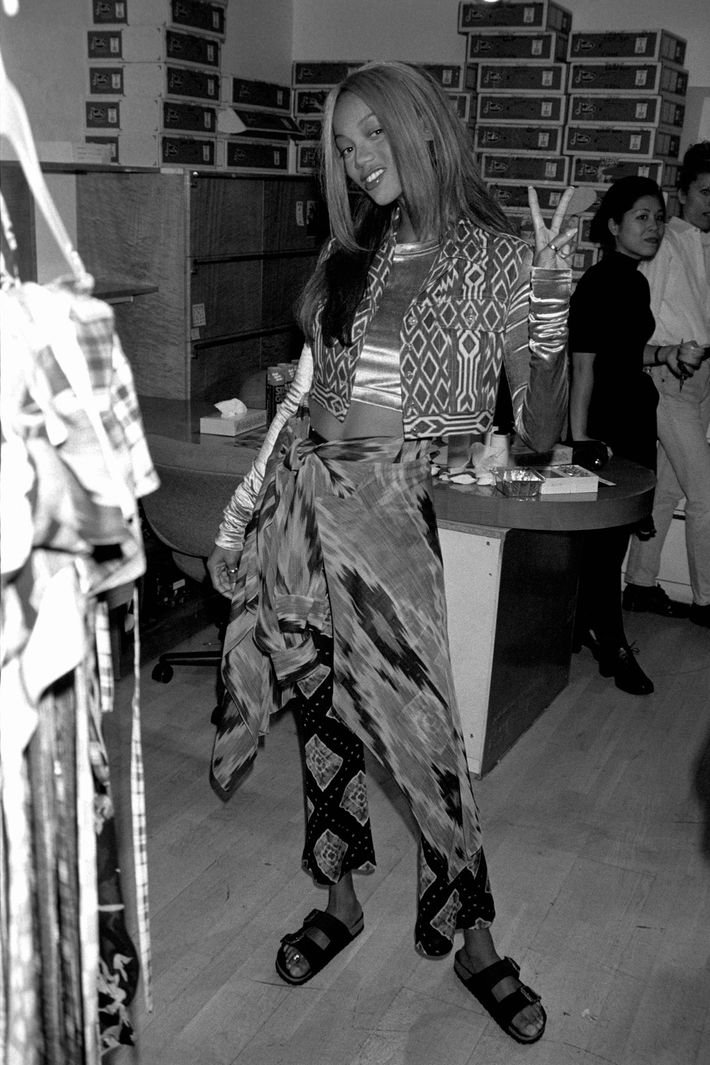

Perry Ellis Grunge Collection

Tyra Banks backstage.

Perry Ellis Grunge Collection

Marc Jacobs’ celebratory finale.