There’s a reason why first impressions are a source of so much anxiety: It’s simply impossible to know how someone meeting you for the first time is going to respond to you, and whether they’re going to accurately or positively gauge who you are as a person. And as Heidi Grant Halvorson, a Columbia researcher and author of No One Understands You and What to Do About It, told Science of Us last month, these concerns are valid: Once first impressions set in, they can be very hard to change.

What most people don’t realize is that as tricky as cultivating a positive first impression can seem, it mostly comes down to just two things. According to Halvorson, “We’re wired to figure out very quickly” how warm someone is — that is, whether they appear to be a friend or foe — and how competent they are — how likely they are to be able to carry out their intentions toward us.

And the impact of these simple judgements can be huge, Halvorson said: “Something in the 80 to 90 percent range of how positive a first impression is of another person can be explained by those two dimensions alone.” The good news is that while this knowledge won’t guarantee that you ace your first impressions, it does at least reveal the grading rubric: If you know that warmth and competence matter more than just about anything else, you can plan accordingly.

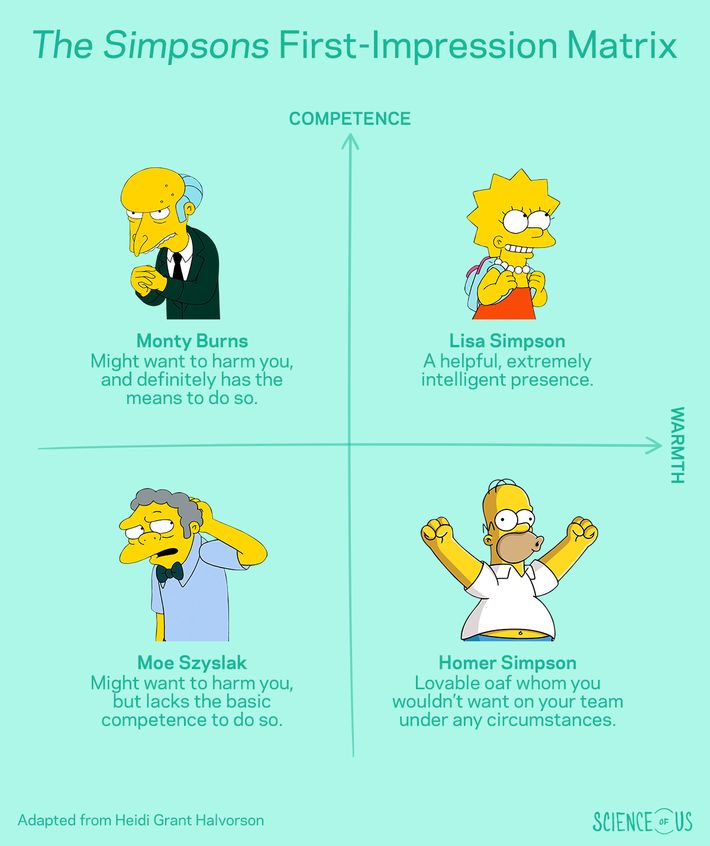

When she’s giving talks about the science of first impressions, Halvorson likes to rely on a simple two-by-two matrix of Simpsons characters she came up with. “I think you can explain every psychological principle with The Simpsons,” she joked.

Here it is, with text added by Science of Us.

There’s an instinctive side to first-impression judgements about warmth and competence, Halvorson said — they’re “basic animal behavior.” Which means, unfortunately, that it’s possible to give off certain signals about your warmth and competence without even knowing it: Since these judgements are largely automatic, even if the person you’re meeting for the first time meeting has never read a word of this sort of research, in all likelihood, you will be slotted into one of these categories, and fairly quickly, too.

The best-case scenario, of course, is to find yourself in the upper-right quadrant. “If you’re high in warmth … and you’re high in competence, you’re like Lisa Simpson,” said Halvorson. “Lisa’s the one you want to be: She’s smart and she’s good, and you feel like she would be a really good friend and you trust her.”

If you half-ass the warmth part, though, and focus only on cultivating an air of competence, you may end up coming off as a Mr. Burns. Halvorson said this is a common mistake when people are nervous. “What people tend to do is really try to show how competent they are — they try to talk about their skills and abilities and what makes them awesome — and they neglect to send warmth signals,” she said. In the absence of these signals, “you end up appearing cold. And cold and competent is Mr. Burns.” Halvorson stressed that if you don’t give off some rather explicitly warm signals, the person you’re meeting’s default response won’t be to see you as “neutral,” but rather as cold — Burns territory.

The flip side of this error is to focus on seeming like a really good, warm guy or gal, but without also broadcasting some indications that you’re competent. If this happens, you’ll end up in the Homer quadrant — maybe a fun person to get a beer with, but certainly not someone whom people would want on their team in a high-stakes scenario. “We tend to feel pity or compassion” toward these sorts of people, Halvorson said — emotions you are probably not hoping to elicit.

Finally, if you really flunk your first impression, you could find yourself in the dreaded Moe quadrant — neither warm nor competent. This “elicits disgust and aversion … you just don’t want to be near that person,” said Halvorson. The Moes of the world are too pathetic to even be feared.

Halvorson said that people have a lot of trouble with how to project warmth. This is understandable: Whereas first-impression evaluations of your competence, in theory, at least, center on tangible stuff like your level of knowledge and prior qualifications, warmth is a bit more amorphous of a concept, and not everyone is naturally good at emanating it.

“Warmth isn’t about being touchy-feely and huggy,” explained Halvorson. Rather, she said, it’s mostly about simple-sounding stuff that people simply forget in the moment: “expressing interest in another person, expressing empathy when that’s appropriate,” to take a couple of examples. Body language is also key: It’s important to look someone in the eye when they’re talking to you, for example, and to “nod a little bit at the end of their sentences,” without overdoing it. And if someone’s smiling at you, make sure to smile back — she said people find it creepy when a smile isn’t reciprocated.

In the heat of an important first encounter with someone, it can obviously be easy to lose track of some of this. If you’re not sure how you come across to new people, Halvorson said the best bet is to simply ask a trusted friend or co-worker, since we’re not very good at evaluating our own performance on complicated social tasks. But if you do end up in the Burns quadrant — or, worse, marooned in Moe’s Tavern — don’t worry: Halvorson has you covered if you need to undo the damage.