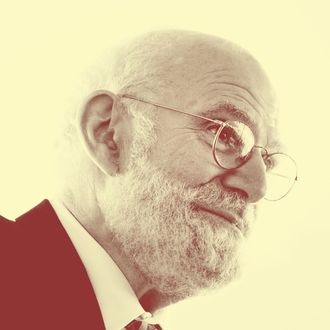

On Sunday, the famed neurologist and author Oliver Sacks died of cancer, specifically of a melanoma that had spread to his liver. With his expressive and often lyrical writing, Sacks managed to explain the nuances of neurology in a way that proved captivating to a wide audience of scientists and nonscientists alike. He most often did this by focusing on individual patient stories, creating in his books and essays moving portraits of the human beings behind often-bizarre neurological conditions.

Here, Science of Us takes a look at some of Sacks’s most fascinating case studies. He’ll be missed.

The brain-damaged Hare Krishna who believed he had reached enlightenment. In his 1996 book An Anthropologist on Mars, Sacks tells the story of a 25-year-old named Greg, a Hare Krishna who had developed an enormous and destructive tumor, which eventually caused him to go blind. When Sacks met Greg in the late 1970s, he appeared “bland, placid, emptied of all feeling” — a serene state his fellow Hare Krishna mistook for enlightenment. “He was fat, Buddha-like, with a vacant, bland face, his blind eyes roving at random in their orbits, while he sat motionless in his wheelchair,” Sacks wrote. Although the young man did not actually believe that he was blind, and thus did not see the need to learn Braille.

When his Krishna pals visited him in the hospital, they encouraged this line of thinking, Sacks wrote. They would “flock around him; they saw him has having achieved ‘detachment,’ as an ‘Enlightened One.’”

The conductor who lost all his memories — but could still remember both music and his wife. Musician Clive Wearing, who was also a conductor, in 1985 contracted herpes simplex encephalitis, a viral infection that attacks the central nervous system. It left him with what Sacks called “the most severe case of amnesia ever documented”: Unable to form any new memories that lasted longer than 30 seconds, Wearing became convinced every few minutes that he was fully conscious for the first time. After the infection ravaged his brain, Wearing began to fill notebooks with entries like this:

8:31 AM: Now I am really, completely awake.

9:06 AM: Now I am perfectly, overwhelmingly awake.

9:34 AM: Now I am superlatively, actually awake.

Sacks recounts Wearing’s story in a chapter of his 2007 book Musicophilia.

The family man who snubbed his wife and child — but loved strangers — after brain surgery. After surgery to treat his epilepsy, a 50-year-old husband and father was never quite the same. He began to keep his distance from family members, refusing to attend holiday celebrations or his 11-year-old daughter’s basketball games, Sacks and his colleagues reported in a 2003 article published in Epilepsy & Behavior. “On one occasion his wife stumbled and put her hand on his knee to right herself, but he coldly told her not to touch him,” Sacks and his co-authors wrote.

At the same time, he “now warms to strangers instantly,” they continued. “He speaks more readily and is more animated with people at the supermarket, laundry, and shoe store than with his family.” Before the surgery, he hated the hospital, but in the months afterward he greeted his physicians as if they were long-lost friends. “The patient now greets his neurologist with a bear hug, repeating how wonderful it is to see him and clasping his hand for more than a minute.” The case report does not include a definitive explanation as to the patient’s change in behavior, but they do include a name for the condition, calling it “selective emotional detachment.”

The psychiatric patients who appeared to wake from the dead. Perhaps the most famous of all of Sacks’s work is the story that inspired the 1990 Oscar-winning film Awakenings, in which Robin Williams played Sacks. (Sacks first wrote a book on the subject, which was published in 1973 under the same name.) The story goes like so: Dozens of psychiatric patients in a Bronx hospital had lived for decades in a trancelike state, the lingering effect of an encephalitis lethargica epidemic, which happened just after the First World War. The disease is often called the “sleeping sickness,” and for good reason: Sacks’s patients were conscious, but just barely, and most of them were all but paralyzed.

And then, Sacks had an idea, sparked by an article in a neurology journal about a chemical called L-DOPA. He had a hunch that the chemical, which converts to the neurotransmitter dopamine in the body, could help the encephalitis patients. It worked. The patients roused back to life, many of them realizing for the first time that they had lost several decades to the sleeping sickness.

The man who developed “hypersexuality” after brain surgery. In 2010 in the journal Neurocase, Sacks again reports the case of a (different) patient who experienced a dramatic change in behavior after he had surgery to treat his epilepsy. This man, who was 51 and married, developed “hypersexuality,” a condition that “started with increased marital intercourse and masturbation,” and escalated to the point where he was downloading child pornography, a crime for which he was eventually convicted and imprisoned.

The woman who was haunted by dragons. Last fall, Sacks was a co-author on a case study published in The Lancet, which told the story of a Dutch woman who reported to her physicians that human faces would transform into dragon visages, right before her eyes. A face that would at first appear normal would soon turn “black, grew long, pointy ears and a protruding snout, and [display] a reptiloid skin and huge eyes in bright yellow, green, blue, or red.” Other times, the hallucinations appeared out of nowhere: Throughout the day, she would see “similar dragon-like faces drifting towards her … from the walls, electrical sockets, or the computer screen … and at night she saw many dragon-like faces in the dark.”

The man who mistook his wife for a hat. The title of one of Sacks’s most famous books is taken from the case study of Dr. P., a man with visual agnosia, who could, technically, see the world around him — he just didn’t always understand it correctly. Sacks determined that Dr. P. was suffering from visual agnosia, a rare condition caused by damage to the brain’s occipital or parietal lobes, which is “characterized by an inability to recognize and identify objects or persons,” according to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

And his visual confusion didn’t end with mistaking poor Mrs. P. for a hat, as Sacks recounts in the 1998 book. “For not only did Dr. P. increasingly fail to see faces, but he saw faces when there were no faces to see: genially, Magoo-like, when in the street he might pat the heads of water hydrants and parking meters, taking these to be the heads of children; he would amiably address carved knobs on the furniture and be astounded when they did not reply,” Sacks wrote.