A little more than a month ago, a study in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Science arrived with a shocking message: Middle-aged white Americans, unlike just about every other subgroup in the wealthy world, had seen their mortality rates increase between 1999 and 2013. The study, by the husband-and-wife team of Princeton economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton, generated a great deal of publicity and speculation as to the root causes of what Case and Deaton described as deaths “largely accounted for by increasing death rates from drug and alcohol poisonings, suicide, and chronic liver diseases and cirrhosis.”

After the paper was published, Columbia statistician Andrew Gelman critiqued the authors’ methodology, launching a mini-controversy. Case and Deaton, he argued, should have “age adjusted” their numbers, meaning they should have accounted for the fact that between 1999 and 2013 the composition of white people ages 45 to 54 in the U.S. itself got a bit older (that is, an increasing proportion of people 50 and older as time went on, for example), which could itself account for the increasing mortality rates. Case and Deaton also appear to have slightly glossed over some important gender differences present in the data. With the proper tweaking in place, Gelman explained, the story is a bit more complicated.

Now he and Jonathan Auerbach, a political scientist also at Columbia, have submitted a letter to PNAS laying out their findings, and Gelman has posted an unabridged (it still isn’t long) version to his website. It’s a nice summary of what’s going on here. The key finding is that once age adjustment and gender differences are taken into account, it appears to be the case that “The mortality rate among white non-Hispanic American women increased from 1999–2013. Among the corresponding group of men, however, the mortality rate increase from 1999–2005 is nearly reversed during 2005–2013.” So over that entire period, things have progressively gotten worse for women and stayed flat (after an increase and a decrease) for men. In both cases, it’s bad news, and at no point has Gelman debated the basic line that this is troubling data that needs further investigation and explanation.

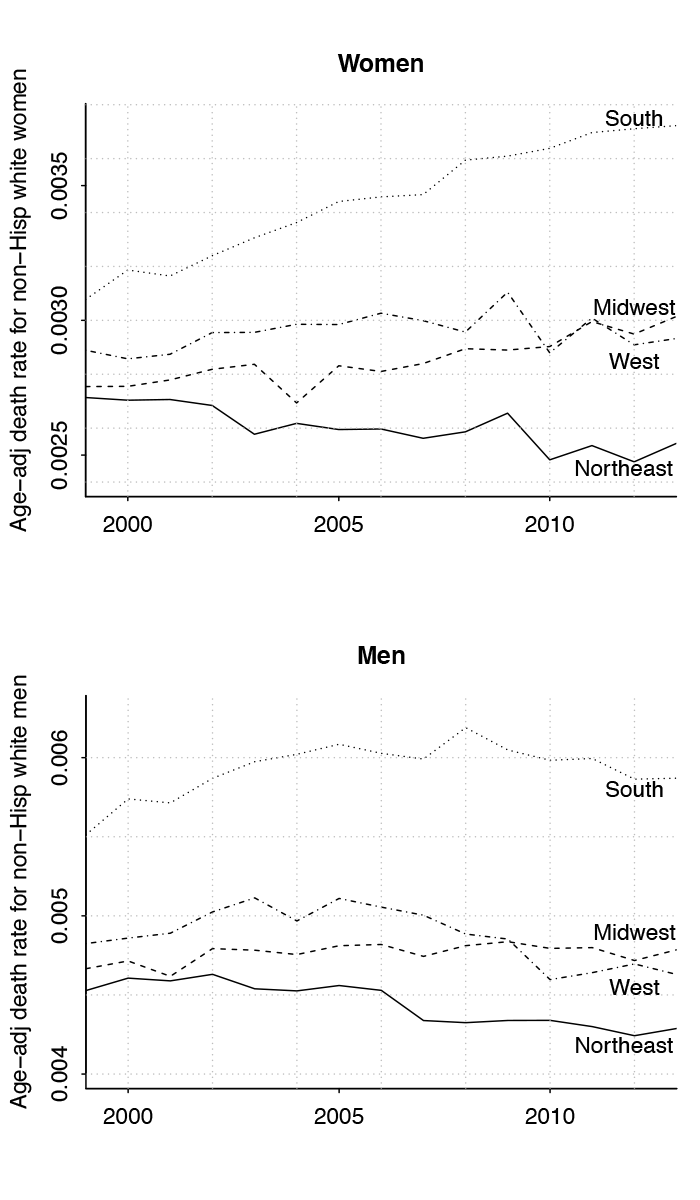

Their letter also includes a couple of nice graphs breaking things down by region, capturing some serious health disparities between different parts of the country:

“The most notable pattern,” the authors write in the caption, “has been an increase in death rates among women in the south. In contrast, death rates for both sexes have been declining in the northeast.” This wouldn’t be the first time researchers have observed these sorts of differences, though Gelman declined to speculate about the specifics in this case. There’s a lot to unpack in Case and Deaton’s sad findings, and researchers are going to be sorting through them for a long time.