Does Encouraging Suicide Make You a Killer?

<span class="message_body">A teenager sent her depressed boyfriend hundreds of messages prodding him to kill himself.</span> Now she's been charged with manslaughter.

Conrad Roy’s loved ones called him Coco. His grandfather was Conrad Sr.; his father was Conrad Jr., “Co” for short, so Coco was a good fit. He was thin but athletic, with brown hair that was often covered by a Red Sox hat; in high school he played baseball and rowed crew. He grew up in Mattapoisett, Massachusetts, a small coastal town 65 miles south of Boston where his grandfather owned a tugboat company. Roy followed in his grandfather’s and father’s footsteps, earning his captain’s license in 2014. He was 18.

As a teenager, Roy struggled with extreme social anxiety and depression. When he was 17, he overdosed on acetaminophen and ended up in the hospital. “He felt like he wasn’t heard by professionals,” his mother, Lynn, said. “He went to a lot of therapists and counselors.”

A few years earlier, Roy had met a girl named Michelle Carter on vacation in Naples, Florida. Carter, whose grandparents were friends with Roy’s great-aunt, lived nearly an hour away in Plainville, Massachusetts. A year younger than Roy, Carter had long blonde hair and blue eyes framed by thick, dark lashes. Like Roy, she was athletic, and she was popular in school — but she also struggled with mental health issues of her own.

After the trip, Roy and Carter struck up a thoroughly modern teenage romance: texting, telling each other their secrets, saying they loved each other, but only meeting in person, as far as his family knows, a couple of times. The relationship continued on and off for three years and many thousands of messages. It ended in 2014 with Roy’s suicide and an involuntary-manslaughter charge against Carter for making him do it.

Roy spent Saturday, July 12, with his mother and two younger sisters. He had graduated from high school a month earlier with a 3.88 grade point average; he had been accepted to Fitchburg State University but had decided not to go. His mom tried to get her son to talk as they walked along the beach with their dog that day, but, she would later say, he seemed distracted by his phone. He seemed like he wanted to sit in the car and text.

Lynn would learn only later that the person on the other end of those messages was Carter. The conversation was about Roy’s plan to commit suicide.

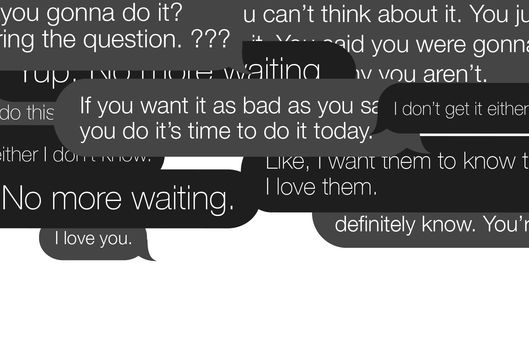

At 4:19 that morning, Carter messaged him. “You can’t think about it. You just have to do it. You said you were gonna do it. Like I don’t get why you aren’t.”

“I don’t get it either,” he wrote back. “I don’t know.”

Carter: “So I guess you aren’t going to do it then. All that for nothing. I’m just confused. Like you were so ready and determined.”

Roy: “I am gonna eventually. I really don’t know what I’m waiting for but I have everything lined up.”

Carter: “No you’re not, Conrad. Last night was it. You kept pushing it off and you say you’ll do it, but you never do. It’s always gonna be that way if you don’t take action. You’re just making it harder on yourself by pushing it off. You just have to do it.”

Later in the afternoon, he wrote her again.

“I’m determined,” he said. “I’m ready.”

“Good because it’s time, babe,” she wrote back. “You know that. When you get back from the beach you’ve gotta go do it. You’re ready. You’re determined. It’s the best time to do it.”

After Roy returned from the beach, he worried about leaving his family behind: “I just don’t know how to leave them, you know.”

“Say you’re gonna go to the store or something,” she said.

“Like, I want them to know that I love them,” he said.

“They know,” she wrote. “That’s one thing they definitely know. You’re overthinking.”

“I know I’m over thinking. I have been over thinking for a while now,” he wrote back. And then, a bit later, he said: “Leaving now.”

“Okay. You can do this,” she said.

“Okay, I’m almost there,” he wrote back.

He sent the message at 6:25 p.m., then told his mother he was leaving the house to visit a friend and not to expect him home for dinner. He made a short drive to a remote corner of the Fairhaven Kmart parking lot. At 6:28 p.m., he called Carter and talked to her for 43 minutes. At 7:12, she called him. The call lasted 47 minutes. During that conversation, as the cab of the truck filled with gas fumes, Roy decided to get out, Carter later told a friend. In a message she probably didn’t expect to ever become public, she wrote: “I fucken told him to get back in.”

The following day, police found Roy’s body in his truck at the Kmart parking lot, a combustion engine next to him. Roy was dead from carbon-monoxide poisoning.

In the days after his death, police officers gained access to Roy’s phone. They found all his text-message threads erased except for one: the texts with Carter. The officer leading the investigation, Scott Gordon, scrolled back through the thread. To his astonishment, Carter appeared to have been not discouraging Roy’s suicidal thoughts but egging them on.

“How was your day?” Roy asked, in one of the exchanges.

Carter: “When are you doing it? … :) My day was okay. How was yours?”

Roy: “Good.”

Carter: “Really?”

Roy: “Yes.”

Carter: “That’s great. What did you do?”

Roy: “Ended up going to work for a little bit and then just looked stuff up.”

Carter: “When are you gonna do it? Stop ignoring the question. ????”

Carter and Roy discussed the methods by which he could commit suicide via carbon-monoxide poisoning. When Roy didn’t think his generator would work, she suggested other ways to obtain one. “Do you have any at work that you can go and get?” she said. “Yeah, probably, ha ha,” he texted back. “GO GET ONE,” she wrote.

They continued on like this for around a week. When Roy waffled or worried for his family, she tried to calm him down. “They will move on for you because they know that’s what you would have wanted,” she wrote. “They know you wouldn’t want them to be sad and depressed and be angry and guilty. They know you want them to live their lives and be happy. So they will for you. You’re right. You need to stop thinking about this and just do it.”

In February 2015, Carter was indicted on charges of involuntary manslaughter by a grand jury, which found “sufficient evidence that Carter caused Conrad’s death by wantonly and recklessly assisting him in poisoning himself with carbon monoxide.” Carter was indicted as a youthful offender — a legal distinction that, unlike other juvenile-court proceedings, makes portions of her court record available to the public. In August, some of the text messages prosecutors included in a court filing hit the internet. The reaction was near-universal revulsion. “It’s now or never: Texts reveal teen’s efforts to pressure boyfriend into suicide,” blared a headline in the Washington Post. “That girl is a monster,” one woman wrote on a Facebook page that posted news of Roy’s death. “God I hope she pays for her hand in his death!!” wrote another. “The angelic Massachusetts teen Michelle Carter texted suicidal sweet-nothings to her depressed 18 year old boyfriend,” wrote Radar Online.

She was portrayed as a teenage black widow, a classic sociopath, a manipulative and craven attention-seeker. In its piece, Radar Online called her one of the worst people of 2015.

After word of her indictment broke, Carter’s classmates at King Philip Regional High School weren’t sure what to think. They closed ranks, declining to gossip about her in the press. A few even confronted a local reporter for treating her unfairly.

Before all of this happened, she’d been a well-liked kid. “In middle school, she was the star athlete and had a lot of friends. She was so good at softball,” one of her former classmates remembered. Students invariably described her as chatty, excitable, and outgoing; she was even chosen as the “class clown” and the person “most likely to brighten your day” in the senior-class superlatives, which were voted on after Roy’s death but before the charges hit the news.

“She was always very bubbly,” said one friend, who remembered that Carter would crack up her classmates by asking questions in health class that she knew were silly and obvious. “It was very genuine. She hadn’t had experience with drugs, alcohol, or sex when I knew her. She was kind of dense when it came to common sense but really smart with school — she tried hard. Michelle made everyone laugh all the time — even her laugh made people smile because it was this booming, genuine sound.”

But it was also apparent to those who knew her well that Carter was struggling with some serious issues of her own. “I think she hid her detrimental mental-health issues,” one of her friends said. Her weight fluctuated dramatically over short periods of time, former classmates remember, and she sometimes made vague reference to treatment she’d received at McLean Hospital, the large psychiatric treatment center affiliated with Harvard University. One classmate said that before Roy died, she heard other classmates say that they were concerned that Carter might become suicidal. “A lot of people started to worry about her,” the student said. “I think that there were definitely mental issues she was going through, and she found comfort in the relationship with Conrad.” Carter’s lawyer, Joseph P. Cataldo, confirmed to me that Carter had been treated at McLean Hospital, but declined to say more about it.

If Carter’s mental health is pertinent to this case, though, it is not the defense her attorney is using — at least not in public. What he argues is that the messages released by the prosecution don’t tell the whole story. He has released only a few texts to support his version of the story, but he says the larger body of the messages show a confused teenage girl struggling to help her severely depressed boyfriend. A few weeks before Roy’s death, he said Carter wrote to Roy: “I need to know that you’re okay and that you aren’t gonna do anything.” A few days later, she added, “I’m sorry what I’ve been doing isn’t enough. You know I’m trying my absolute hardest.” According to Cataldo, Roy wrote back, “You don’t understand. I want to die!”

“She was, at the age of 16 and 17, delivered by Conrad Roy a very heavy burden for someone in her position to have to bear,” Cataldo told me. “They had a texting relationship, an online relationship, where he laid out all of his skeletons, if you will, and his issues on her.” On at least two occasions in the texts that are not included in the messages released by prosecutors, Cataldo said Roy asked Carter to kill herself with him. “He said, ‘Let’s do a Romeo and Juliet,’” he says. He says that Roy had previously discussed killing himself a year and a half earlier and that Carter had tried to encourage him to seek help. It was only toward the very end, he says, that she started encouraging him to do it.

The full police report contains other messages — not included in news reports — that depict someone deeply convinced of the need to end his life. Sent from Carter’s email, they contain messages she said Roy wrote to her about why he wanted to commit suicide: “I see the world as a horrible place with a bunch of horrible people,” one of the messages began. “Theres a shortage of good genuine people like you and me who care about other people and not all about themselves. I fear this world so much. I think its getting really out of hand, especially with all these shows and media ruining what culture is supposed to be like. I was born in the wrong generation. I wish I was born in the 1800s when everything was easy, you worked hard and there wasn’t much distractions in the world … I have an extreme desire to die because im a fuck up, because im shy. A bunch of reasons I could go on for hours about how I hate the world.”

“There’s nothing anyone can do for me that’s gonna make me wanna live, its very bad to hear but I want you to know that,” another message said. “Truthfully, I haven’t been happy with myself ever. You and my family are the only things that make me happy. But I have split personalities and I don’t know who I am … Theres something wrong with my head and it needs to end.”

Few psychologists or psychiatrists I spoke with were willing to discuss the case and what happened between Carter and Roy. Was she manipulating him in a ploy for sympathy? Frustrated by his repeated talk of suicide? Afraid of being pushed to participate in a suicide pact? Did she think, in some inexplicable way, that she was doing the humane thing in encouraging him to die? It’s impossible to say for certain, maybe because her defense has not offered a deeper explanation for why she would behave this way. Or maybe it’s because there is nothing that could ever really explain it away. (Carter's lawyer declined to make his client or her family available for comment. The prosecution also declined to speak on the record.)

Carter and Roy were, in a way, replicating a disturbing dynamic that happens in some online forums, where the severely depressed can gather and discuss best practices for self-harm and suicide. “Without being able to understand what each person might be going through personally, it certainly seems to be the case that those who experience mental illness can end up reinforcing maladaptive behaviors accidentally, or because they’re not resourced to know how to better help,” said Mitch Prinstein, a professor of clinical psychology at the University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill who studies peer-to-peer relationships and their effects on teen depression and self-harm.

Prinstein said that the experience of having a close friend or loved one talk repeatedly about suicide can be a major stressor for anyone, but especially a young person. “There is plenty of evidence to suggest that the experience of being in a close relationship with someone who is depressed is a difficult experience for that non-depressed partner,” he said. But he doesn’t think that can explain the body of text messages released as part of the indictment. “Despite the distress that might form from being in a relationship with someone depressed or suicidal, there’s no reasonable explanation for the type of aggressive and demanding behavior” displayed in the messages, he said.

This is what makes the messages so hard to dismiss: Even in moments when Roy seemed to be reconsidering, Carter pushed him forward.

“Like why am I so hesitant lately. Like two weeks ago I was willing to try everything and now I’m worse, really bad, and I’m LOL not following through. It’s eating me inside,” Roy wrote the day of his death.

Carter: “You’re so hesitant because you keep over thinking it and keep pushing it off. You just need to do it, Conrad. The more you push it off, the more it will eat at you. You’re ready and prepared. All you have to do is turn the generator on and you will be free and happy. No more pushing it off. No more waiting.”

Roy: “You’re right.”

Carter: “If you want it as bad as you say you do it’s time to do it today.”

Roy: “Yup. No more waiting.”

Carter: “Okay. I’m serious. Like you can’t even wait till tonight. You have to do it when you get back from your walk.”

To the outside world, Carter seemed to genuinely care about Roy. Her high-school friends said she would frequently talk about him, and she told him she loved him in the days before his death. After Carter told him he had to commit suicide today, he responded: “Thank you.”

“For what?” she responded.

Roy: “Still being here.”

Carter: “I would never leave you. You’re the love of my life, my boyfriend. You are my heart. I’d never leave you.”

Roy: “Aw.”

Carter: “I love you.”

Roy: “Love you, too.”

One of Carter’s defenders, a friend from school, said she thinks Carter’s mental-health issues played a role in what transpired between them. “This case is about two unstable teenagers, one of whom was very suicidal and the other that had no clue how to handle the situation,” she said. “I think Michelle went through stages of handling Conrad; first, she tried really hard to change his mind; then, she felt she couldn’t convince him so she resorted to something she found on the internet to comply with his plans; and finally, I think she started to realize the longer the plans went on that Conrad was really going to go through with it,” she said. “I truly believe that Michelle was delusional about Conrad’s situation.”

There are very few instances in the United States of someone’s successfully being convicted of causing another person’s suicide — a person who kills himself is generally considered to be the ultimate cause of his own death. Most states, though, have specific laws criminalizing the aid or assistance in someone else’s suicide. Massachusetts is one of the few states in the country without a specific law against it.

In recent years, there’s been a small but growing number of criminal charges leveled against young people who cyberbully peers who later commit suicide, most famously the six students criminally charged for bullying in the suicide of Phoebe Prince, another Massachusetts teenager. The case against the teenagers involved in Prince’s death ultimately ended in plea deals for misdemeanor charges, with the more serious charges dropped amid criticism that the prosecution had overcharged the kids.

Successful convictions against teenagers charged in peer suicide deaths have proved elusive for prosecutors, and the Carter case is likely to be just as challenging. “I think they have a very thin case. I’m surprised they even charged this girl,” John M. Xifaras, a retired superior-court judge for the state, told South Coast Today, a local news site. “It’s going to be a very difficult case to prove,” a former Massachusetts District Court judge said. “She didn’t put the instruments in his hand.”

There is one contemporary case that could serve as an example. In 2011, a Minnesota nurse named William Melchert-Dinkel was found guilty of posing in online chat rooms as a depressed woman in her 20s and persuading at least two people to kill themselves. The state supreme court reversed Melchert-Dinkel’s convictions in 2014, ruling that “advising or encouraging suicide” is protected by the First Amendment, while actually “assisting” in someone’s suicide was a criminal act under state law. Last year, an appeals court upheld the conviction against Melchert-Dinkel in one of the suicide cases, for providing detailed instructions to a man who later killed himself.

Matt Segal, the legal director for the Massachusetts ACLU, says there are two major hurdles for the state in pursuing this case. “One is the First Amendment, and the question there is, did the young woman have a constitutionally protected right to say what she did to this young man? And even if she didn’t have the right, did saying those things amount to a crime under Massachusetts law? That might be an easier question if Massachusetts had a statute about assisting suicide, but it doesn’t have one, so to win on that second question they will have to prove the elements of manslaughter. That really seems like an uphill climb for the prosecution.”

When investigators interviewed Carter’s friends after Roy’s death, they told them that she had a tendency to exaggerate and needed a lot of reassurance and attention. Even the friends who were sympathetic toward her had to contend with messages that were difficult to dismiss, ones that felt calculating and aware.

Two days before Roy set off for the Fairhaven Kmart, she practiced her response to Roy’s death with friends, acting as if he were already gone. She texted a friend: “Like, he always texts me in the morning and he didn’t and he stopped answering last night.” She said she had reached out to Conrad’s mother, who said the family was looking for him but couldn’t find him. None of this was true, but it would be a few days later.

On the day Roy died, Carter asked him, “did you delete the messages?” as though she knew exactly how bad they’d look after his death. In one of the most disturbing exchanges included in the case against her, Carter messaged a friend named Sam just over a week after the suicide, worrying about the legal implications of her role in his death. “I just got off the phone with Conrad’s mom about 20 minutes ago and she told me that the detectives had to come and go through his things and stuff,” she wrote. “It’s something they have to do with suicides and homicides and she said they have to go through his phone and see if anyone encouraged him to do it on text and stuff. Sam, they read my messages with him I’m done. His family will hate me and I can go to jail.” Carter’s friend tried to console her, but she wasn’t convinced. She would later tell her friend that she had been on the phone with him when he took his final breaths.

Investigators would later learn that from July until December of that year, Michelle had been messaging Roy’s mother. In one message, she wrote, “You tried your hardest, I tried my hardest, everyone tried their hardest to save him … He was the most important person in the world to me, I saw my life with him. I wish things could be so different now too, but you need to know that it is not your fault,” she wrote. In another message she told Roy’s mother, “He thought he would never be truly happy with himself. And he didn’t think he’d be a good husband or father and didn’t want his kid to have the same problem … but you can’t blame this on you, please. It won’t solve anything and it makes it harder living with the guilt.” Later, when officers obtained a subpoena of Carter’s phone records, they saw that she had continued to text Roy’s number more than 70 times after his death.

In one of the messages Carter sent to a friend after the fact, she wrote of her guilt over his death. It’s hard to know how to decipher her words, where the manipulation ends and the sincere confusion begins. But in them, she wrestles with her sense of responsibility and guilt over his death. “His death is my fault. Like, honestly I could have stopped it. I was the one on the phone with him and he got out of the car because [it] was working and he got scared and I fucken told him to get back in … because I knew that he would do it all over again the next day and I couldnt have him live the way he was living anymore.”

“I couldn’t do it. I wouldn’t let him. And therapy didn’t help him and I wanted him to go to McLeans with me when I went … but he didn’t want to go because he said nothing they would do or say would help him or would change the way he feels. So I, like, started giving up because nothing I did was helping but I should have tried harder,” she continued. “Like, I should have did more. And its all my fault because I could have stopped him but I fucken didn’t. And all I had to say was I love you and don’t do this one more time and he’d still be here.”