New York is place where we use fashion to announce ourselves and speak to others, resulting in eye-catching, era-defining looks. But which of these style periods was truly the best? Ahead, a roundtable debate with our expert panel: Simon Doonan (writer and creative ambassador-at-large to Barneys), Robin Givhan (fashion editor, Washington Post), Mickey Boardman (editorial director, Paper), and Laurie Simmons (artist).

Doonan: The ’80s drag/Susanne Bartsch/Salon de Beaute/burlesque/vogue/Copa years. During the AIDS crisis, there was a surge of stripper-chic and megatheatricality — a fabulous antidote to fear and misery.

Givhan: That era of Breakfast at Tiffany’s. It’s during the early ’60s, but people still dressed like it was the 1950s — vaguely formal. The politics of the era I’m pushing aside. Aesthetically, people looked so spectacular. A counterpoint to that is the 1990s, when ghetto fabulous was all the rage. Hip-hop was coming into its own, and there was a wonderful, gaudy celebration of success that was broad, diverse, and unapologetic. I see those bejeweled Gucci jeans, and I smile.

Boardman: I love when decades change but the fashion hasn’t caught up yet. I go for the late ’60s, early ’70s, when you have mothers dressing like Lana Turner and daughters dressing like Janis Joplin and sometimes you had a combination, like an old society lady wearing Pucci hippie dresses.

Doonan: The movie Midnight Cowboy perfectly captures that NYC fashion schism. White-gloved Upper East Siders versus freaky outsiders like Viva.

Simmons: Early-’60s dress-up was the first era that came to mind, and I (sort of) witnessed it. My father had this love affair with Arnold Constable & Co. because he’d seen Eleanor Roosevelt there and claims she smiled at him, so once a year he took my two sisters and me to buy winter coats and matching hats, which we wore to see the Christmas lights in department-store windows. I remember seeing incredible coats and fancy hats. By the late ’60s, the combo of the end of Carnaby Street and high hippie was making for some incredible street fashion with many, many visible human hours of jean embroidery — mine included. Mainly, I want to disclose that my friends and I walked around barefoot.

Givhan: Dashing down the street in an evening gown to catch a cab is very New York to me. But I do think it is being dismantled by yoga pants and hoodies, the failure to shower and put on real clothes that afflicts most other American cities.

Plus: 4 Iconic Style Moments

Linda Wells on Diana Vreeland, 1981

On a spring evening, I saw Diana Vreeland on East 65th Street and it stopped me cold. The night was already pretty magical. My father was in town on business, and we’d had pasta primavera and Champagne at Le Cirque, as one did in that particular place at that particular time. As we made our way from the restaurant, there she was, strolling down the street. Vreeland was in full geisha mode: Her jet-black hair was brushed off her face, her skin was powdered white and flushed in vivid rouge, her chin tilted up regally. She was wearing a long embroidered coat and little babouche slippers, which, in my memory, were pale yellow. Because it was a perfect moment, she was on Halston’s arm.

I may have gasped. I was a transplant from St. Louis, and Vreeland represented my fantasy of New York, a place where you could decide who you wanted to be and then will it into existence. Vreeland was breathtaking not because she was beautiful but because she was so elaborately, deliberately decorated. She was thoroughly self-created. As she passed with this tiptoe-y walk, she glanced over her shoulder and said, “Well, hello.”

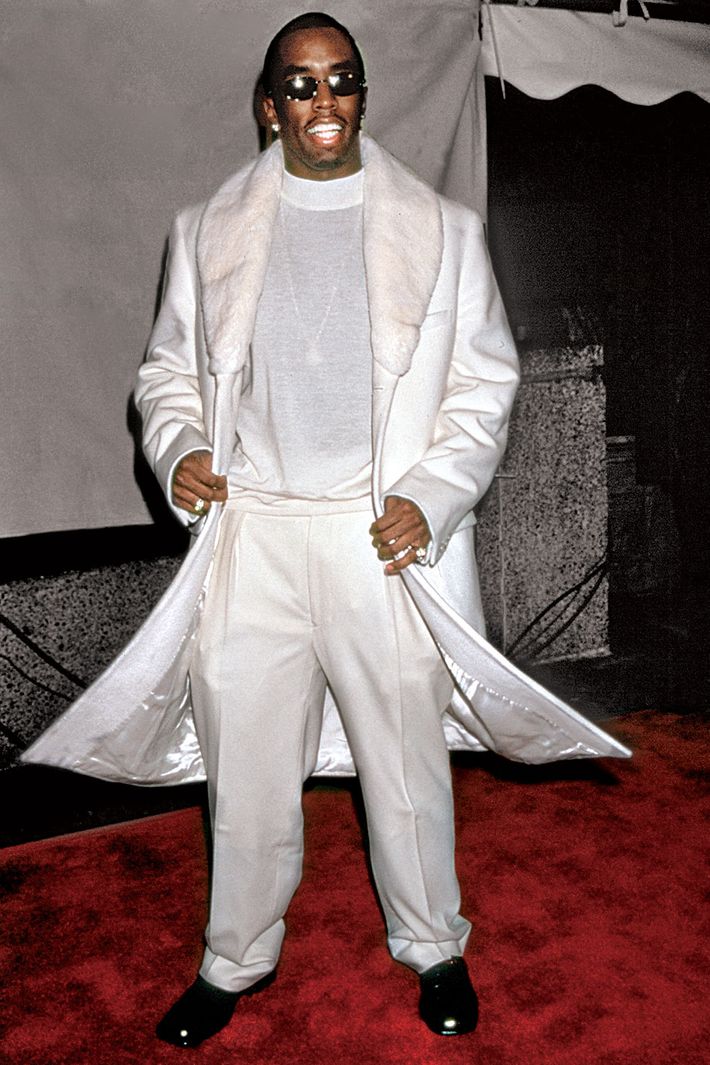

Rembert Browne on Puff Daddy, 1997

I was 10, watching the 1997 MTV Video Music Awards on television, and he was the closest thing I’d ever seen to an angel.

There was a choir, a video montage of the slain Notorious B.I.G., and then — out of a tunnel — Puff Daddy. He glided across the stage as the guitar riff of “I’ll Be Missing You” began, dancing in a white-and-cream vest-suit. I wasn’t thinking about fashion at the time, but I couldn’t take my eyes off him. It was only later that I would realize how much watching Puffy as a kid in Atlanta influenced my ideas about how a man could present himself in New York, a decade before I signed my first lease. The thing I admired about Puffy was not any particular style or taste but just that he always looked the part. And given that he is the consummate slasher (rapper slash producer slash actor slash designer slash vodka baron slash …), that meant that he looked the part everywhere, doing everything, effortlessly belonging. He’s a chameleon, but not a phony. We’ve seen him comfortable in the club, the boardroom, the gala, and in the projects. And he’s done it without an ounce of code-switch. For better and worse, it’s always Puff.

There’s Sean John formalwear, Sean John velour, and Sean John denim. There was the part in his hair, the grill and toothpick in his mouth, the big shades on his face. There was leather of every size and color, jerseys from any team or sport, fur coats in the North and South. There was bathrobe Puff, “Vote or Die” P. Diddy, and tracksuit Diddy. He gave us the Hamptons “White Party,” the pink parasol at Burning Man, the New York City Marathon fauxhawk. And perhaps at his most chic, there was “Puffy Takes Paris,” his 1999 Vogue spread alongside Kate Moss.

But despite all his costume changes, there’s an authenticity in the way he’s presented itself, which is entirely aspirational. He is both where he came from and where he is now, all at once. He’s never wavered. He’s been playing dress-up his whole career.

It’s unclear if Puff ever really started anything in terms of trends. But origination is not where his strength lies — it’s Diddy as you, Diddy as me. And while it may seem as if he’s the master of reinvention, it’s actually just addition. Because for two decades Puff’s looks never die, they simply multiply.

Cathy Horyn on Nan Kempner, 2001

That July, I found myself perched on a windowsill at Yves Saint Laurent in Paris, watching Nan Kempner strip down to her pantyhose. She was with two other clients, Deeda Blair and Patricia Altschul. The room was about the size of a middle manager’s office. Cigarettes burned in an ashtray. It was ten o’clock on the morning after Saint Laurent’s couture show — one of his very last, as it turned out, though nobody thought that way then. You thought, in fact, that there would always be long rows of ladies at those shows and that you would know most of them well enough to be invited into their dressing rooms to watch them decide what to buy. The rise of China, social media, Rihanna, the lopping off of the name Yves from the Saint Laurent label — this was all still to come. On that morning, we were just four American gals in a room, with the top-dog gal, Nan, stepping into a cloqué velvet dress that probably still had the body heat of the model who had worn it.

She loved clothes. She once said that she bought “more than I should, and less than I want,” and that she hoped to be buried naked because she knew there’d be shopping where she was going. People of course made fun of her “social X-ray” body — the bony chest, the 26-inch waist, the matchstick legs. She stayed so thin, in part, to be able to fit into runway samples, which traditionally were sold at the end of the season at a hefty discount. But “ghastly thin” has been on the French style menu since Baudelaire, and I think, for better or worse, it suited Nan. As Harold Koda said in 2006, for the opening of an exhibition at the Met dedicated to her style, “She wore couture like sportswear.” That’s why she stuck to Saint Laurent over the years and why you almost never saw her in anything that was too froufrou.

Despite the scale of Nan’s wardrobe, it was somehow in proportion — or, anyway, not out of proportion — with the rest of her life. That’s what I admired about her and maybe what people didn’t appreciate about her. She was a relaxed hostess. (She once told me that, in a pinch, frozen toaster waffles with butter and syrup were a great dessert.) And she was practical, in her manner. The living room of her Park Avenue duplex, designed by Michael Taylor around 1960, with silk-paneled walls and low taupe corduroy sofas, was unchanged 40 years later.

In the end, I believe, Nan took only the cloqué dress and a leopard-print chiffon blouse that morning. It’s kind of funny. Today, in our media-blitzed age, you can’t imagine someone going to Dior or Chanel and buying only a piece or two. But that’s precisely how icons learned to dress.

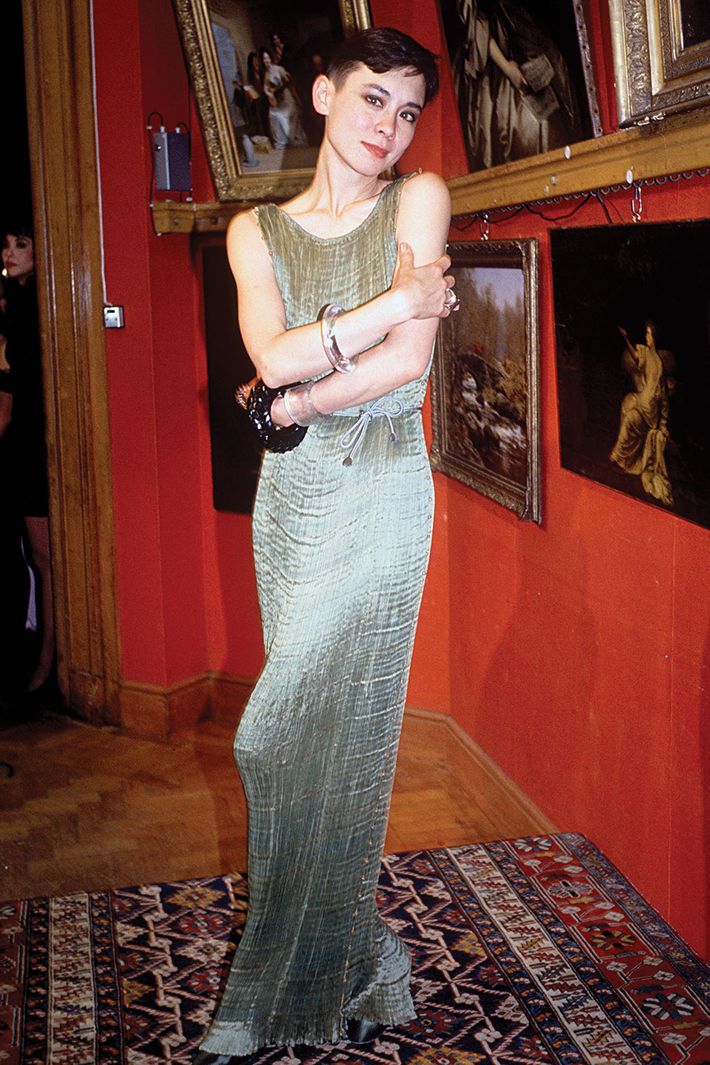

Simon Doonan on Tina Chow, 1985

The exhibition theme at the Met Ball that year was “Costumes of Royal India.” Mrs. Chow arrived with Andy Warhol. Realizing that her simple black frock could use a little szhoosh, she headed to the gift shop. Without dithering, she grabbed a large handful of cheapo red-glass-bead necklaces — Indian-themed tourist fodder — and slung them around her neck. “I came out without a purse,” she said with genuine horror, clutching her new “rubies.” Watching the notoriously parsimonious Andy pull out his credit card made my night.

Tina was effortlessly stylish, but there was something more. The French call it le chien. It’s a mysterious, quiet, confident brand of chic that certain women possess. Cher has it. Debi Mazar has it. Mariacarla Boscono has it. Iman has it. Ditto Chrissie Hynde and Victoria Beckham. Tina Chow had it in spades.

Bettina Louise Lutz was born in Lakeview, Ohio, in 1950. By the age of 16, she was modeling for Shiseido. In 1972, she married restaurateur Michael Chow, and they became the world’s grooviest, most stylish, Jean-Michel Frank–collecting couple. In 1973, mannequin-maker Adel Rootstein recognized that Tina was the girl everyone (in fashion) wanted to look like and immortalized her in fiberglass. I dressed and undressed many Tinas in London shopwindows back in the day.

With her gamine, tomboy simplicity, Tina stood out from the other maquillaged glamour-pusses on the runway. She was Gong Li before Gong Li. She was Tilda before Tilda. She not only collected vintage couture but wore it with unprissy abandon. She would throw on a pleated Fortuny, or a tweedy Balenciaga as if it were an old T-shirt, and waft between the tables at Mr Chow, the grooviest hostess in the world.

Because her style was so edited and spare, it was a surprise when, in later years, she announced that she had begun to design jewelry. Rhinestones? Tiaras? No. If Noguchi or Richard Serra had designed jewelry, it might have looked like Tina’s crystal amulets and sculptural basket-weave bangles.

Tina died of AIDS in 1992 at age 41. During her short life, she was photographed by many greats, including Cecil Beaton, Richard Avedon, Snowdon, Robert Mapplethorpe, Helmut Newton, and the bloke who knew best how to capture her chien, the late David Seidner. Like a latter-day Adele Bloch-Bauer — the subject of Klimt’s masterpiece died of meningitis at the height of her beauty — Tina lives forever in David’s sensational portraits.

After her death, F.I.T. mounted an unforgettable exhibit titled “Flair: Fashion Collected by Tina Chow.” Surveying this exquisite collection — Lanvin, Cardin, Vionnet, plus vintage cheongsams — it was hard to deny the fact that Tina, along with having le chien, also had le taste.

*A version of this article appears in the May 16, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.