Over the summer of 2002, a bunch of us in the “Styles” department at the Times worked on a special section devoted to Bill Cunningham. The directive, and possibly the idea itself, had come from Howell Raines, the executive editor at the time. And it came as a surprise. The Times was still a place of traditions and rules, chiefly about what could be printed in its pages. It was stunning, then, that a paper that still frowned like a Victorian auntie at even the occasional use of first person in a story, would devote a whole section to one of its own — a man who, treasure or not, would have happily yielded to any rule that kept him in the shadows.

My job was to get Bill to talk, like Garbo. Although Bill had written volumes of some of the most insightful criticism on fashion — in Details magazine, which he co-founded — he had all but discouraged interest in his own life. Who knew anything about him, really? He was rumored to be the black-sheep member of a well-to-do Boston family, and these suspicions were fueled by his enormous knowledge of the old-line rich. He knew how they lived and dressed, and moved among them with ease; they even welcomed the spindly character who lived alone in a studio flat at Carnegie Hall and traveled to their mansions by public transportation. Of course, Bill wanted no part of the special section; but I suspect he knew he was licked when some pressure from some quarter of the paper was gently applied to him. He might chafe at the idea of being owned by anyone — a worthy principle — but the truth was the place in his heart for the Times, and especially the Sulzberger family, was huge.

We arranged to meet early one morning in the Times cafeteria in the old building on West 43rd. Since Bill often had his breakfast at the paper, and would be off on his daily rounds of street pictures and then parties, not returning to the building to drop off his film until quite late, my best shot was to corner him over a greasy egg and coffee. I knew Bill moderately well by then. He used to come by my desk to borrow a copy of Women’s Wear Daily. Sometimes he would approach by letting out a high, crowing laugh and say, “Who have you offended today, kid?” We’d talk briefly about the latest fashion atrocity or bruised ego, and then he would depart, mugging a prize fighter’s jab as he said, “Give ‘em hell, Horyn!” Much later, when collegial respect had mellowed to fondness and a kind of trust, he called me Madame Horyn. He’d peer over my cubicle and tease, “Ah, Madame Horyn, you’ve come down from your country seat!” With Bill, though, you could never push. Intimacy had to be on his terms.

On the cafeteria table, I placed my tape recorder between us and gingerly lobbed the first question. Well, why bother to be delicate? For the next two and a half hours Bill talked up a storm. He talked about his childhood, his first camera, his years as a milliner. He talked for so long that I ran out of tape. It was my first real hint that Bill was a mass of contradictions.

To my delight he helped us greatly with the project. He shared some of his rarely seen photos with Philip Gefter, a picture editor at the Times, who helped edit the tribute. He dug out his Harvard transcripts. Far more than any of us realized, I think, Bill wanted to be in control of how his life and work were presented, though I should add he also didn’t try to interfere. As for our conversation, after transcribing the tapes, I made some paragraphs, cleaned up redundant bits, and, with his permission, stuck his byline on top. I doubt he ever read it.

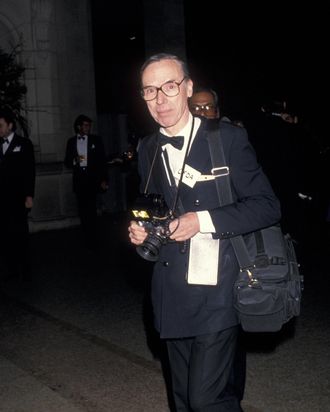

In the days since Bill’s death, my mind has been flooded with images of him. The way he would huddle every Friday with one of the extraordinarily patient copy editors in the “Styles” section as he pulled names and facts from his notes for the Sunday party-page captions, or tweaked the placement of his images. The absolute gift of encountering him on a beautiful spring day outside Bergdorf Goodman as he was photographing people, and seeing him pause in the midst of all that hubbub for a little small talk. The serendipity of glancing out your cab window and seeing Bill on his bike, peddling in the twilight toward some black-tie event. I thought, too, of the times we spent in Paris, mostly in the car of Bernard Alloux, the paper’s driver during the shows. Bill, as many people know, had a horror of accepting anything that seemed a favor, including a ride. But for the far-off or late-day shows he would come with us, and as he got older and more frail this became routine. We would pile into the sedan, with Bill remarking on something he had seen, his deafness causing the general volume to increase, and I would glance over at Bernard, a smile creasing his face, as we raced across Paris toward some god-awful show.

The difficulty of describing what made Bill such a unique talent is that he didn’t conform to any modern category. He worked for the Times, with its many layers and powerful terrains, yet he functioned as a free agent, and in some ways bent the institution to suit him. He knew almost nothing about email or social media — had no interest. Yet over the course of his 50 years with the Times, his photographs revealed an almost infinite number of ideas about culture, fashion, race, and beauty. He lived like a monk, in the same corner of New York for the majority of his adult life, and largely limited his travels to work-related jaunts to Newport, Paris, and Long Island, yet he basically was the eye that recorded a changing world. Bill always said that the only way to know what was happening in fashion was to cover the shows, observe the street, and catch people out at night — to see what clothes from the runway actually sold. But who works like that today, and with almost no thought toward material gain? The only comparable people I can think of are the journalists who worked on the fashion and society pages of the Times at the beginning of the 20th century, women like Anne Rittenhouse and Marie Louise Weldon. They did their main legwork in fashionable restaurants like Delmonico’s, in the parterres of the Metropolitan Opera House, and in the churches where New York’s elite families wed. Their columns were stuffed with names and descriptions of costumes, down to the exact shape of Mrs. Gould’s emeralds.

Bill was the heir to that reportorial tradition and, as well, to the pioneers of street-style photography, the Seeberger brothers, who in roughly the same period took photos of fashionable Parisiennes at race tracks and other places. Of course, Bill expanded on their ideas, and across a wider ocean of time. And if he was the eye on fashion, he also helped raise its prestige in the eyes of the powers that run the Times.

He remained incredibly sharp. Above my desk are two quotes. One is a long passage from The Boys of Summer, Roger Kahn’s book about the Brooklyn Dodgers, in which Kahn quotes Ring Lardner saying that after years of covering too many Major League Baseball games, you tend to observe less and less of each. Your senses become dulled. The same could be said of fashion journalists, but never of Bill. His curiosity and energy were an inspiration to legions of young people.

The other quote, from Proust, addresses the work of genius. To a friend, he wrote: “In fact, I believe there exists for every beautiful sentence an imprescriptible right which renders it inalienable to all takers except the one for whom it waits, according to a destination which is its destiny.” Bill was not Proust. He recorded, rather than conjured, a distinct world. But he was definitely in Proust’s camp. He waited — on street corners, outside restaurants — for the thing that no one else could see. And his destiny was his alone.