It’s pretty easy to predict what happens when white police officers assault a black person and everyone finds out about it: People, particularly African-Americans, will become a bit more fearful and distrustful of police, for perfectly rational reasons. As Matthew Desmond of Harvard, Andrew V. Papachristos of Yale, and David S. Kirk of Oxford write in an important new study in the American Sociological Review, this fear and distrust, coupled with other incidents and experiences, can give rise to what researchers call “legal cynicism — the deep-seated belief in the incompetence, illegitimacy, and unresponsiveness of the criminal justice system … [that] is thought to pervade many poor, minority communities.”

There’s plenty of interview and survey evidence suggesting that a deep-seated legal cynicism hangs like a fog over many of these neighborhoods. But a much-less-studied question, Desmond and his colleagues write, is whether this attitude actually translates into a lack of willingness to engage with police. “When it comes to relying on and cooperating with the police, what one does might not resemble what one says one will do. The legal cynic may report crime just as regularly as the citizen who views the criminal justice system as reverence.” That is: At the end of the day, if you witness a crime, the institution best equipped to respond to it is the police, so neighborhood residents may set aside their anger and disgust to enlist the police’s help.

Desmond and his colleagues wanted to test this idea by seeing whether a shocking, attention-getting incident of police violence would lead to a decline in 911 calls reporting crimes. For their study, they focused on a police-brutality incident that is notorious in Milwaukee: the October 2004 beating of Frank Jude. The story is fairly complicated, but the short version is that Jude, who is black, attended a party hosted by a white cop and some of his fellow officers. Soon Jude and his three companions got uncomfortable and left, heading for the truck they had arrived in. Quickly the truck was surrounded by ten men from the party, who accused Jude and one of his friends of stealing the host’s badge. In the assault that followed, Jude was beaten so viciously by a group of officers that, at the hospital he was taken to, Desmond and his colleagues write, “The admitting physician took photographs of him because his injuries were too extensive to document in writing.” (Not that it would have justified what occurred at all, but there is also no evidence Jude took the badge.)

Both the beating itself and the investigation raised outrage, particularly in the black community: Even though it was obvious who was involved, it took months for any of the perpetrators to be charged, and the Milwaukee Police Department was accused of obstructing the investigation just about every step of the way. Three officers were brought up on charges and acquitted by an all-white jury, but the feds got involved and were able to convict seven out of eight defendants in federal court.

It wasn’t until about three and a half months after the gang assault that the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel brought the news to the city’s — and the country’s — attention with a front-page story: “Police Suspected in Man’s Beating” (the online headline is slightly different). That’s the moment Desmond and his colleagues focused on, because that was when the news fully broke among Milwaukeeans everywhere.

To measure the effects coverage of the Jude incident had on Milwaukee residents’ willingness to interact with the police, the researchers obtained “every 911 call placed in Milwaukee between March 1, 2004 and December 31, 2010” — that’s 1,104,369, or 883,146 when they cut out calls that originated beyond the city limits — complete with full information about the type of call, the address from which it originated, and so on. They wanted to see whether and to what extent knowledge of the incident would affect 911-dialing behavior, and whether there would be a racial differential when they mapped the source onto information about the racial composition of Milwaukee’s neighborhoods (Milwaukee consistently ranks as one of the most segregated cities in the country, it should be pointed out). They focused on crime reporting, not reporting of incidents like fires or car accidents.

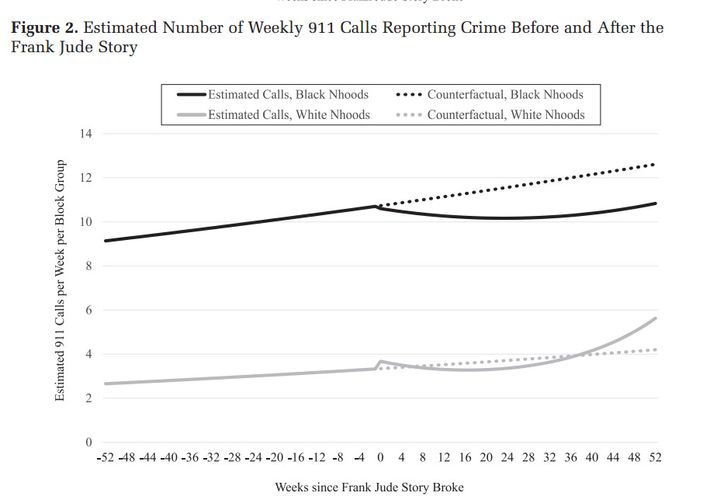

Glossing over some of the complexities of the number crunching Desmond and his colleagues did, here’s the key takeaway, in the form of a graph showing the calls that originated from black and white neighborhoods after the Jude story, compared to what their model suggests should have been the trajectory during that span:

Summing up their results, the researchers write:

In black neighborhoods, the decline in 911 calls is large and durable, with citizen crime reporting dropping and staying lower than expected for over a year after the story broke. In white neighborhoods, by contrast, a small decline in 911 calls followed Jude’s story, but the effect dissipated rapidly as 911 calls eventually surpassed the counterfactual line within a year’s time. The beating of Frank Jude had a much more substantial effect on citizen crime reporting in black neighborhoods than in white neighborhoods.

Overall, the researchers believe that “the police beating of Frank Jude resulted in a net loss of approximately 22,200 911 calls reporting crime the year after Jude’s story broke,” and that’s during a span in which there were about 110,000 911 calls to the police total. And while black people are 40 percent of the population in Milwaukee, “Over half (56 percent) of the total loss in calls occurred in black neighborhoods.” There was no such drop for calls reporting automobile accidents, further supporting the researchers’ theory that the effect had to do specifically with crime reports. Eventually the overall number of calls returned to where it was “supposed” to be.

How do you trace the impact of 22,000 911 non-calls? There’s no easy answer. It’s safe to say that those would-be calls would have contained a lot of information for police, some of it helpful — both reports of crimes that may not have been recorded otherwise, and additional information about crimes that other people did report that may have helped police clear those particular cases. Whatever the details, if Desmond and his colleagues’ model is correct and the Jude beating led to an approximately yearlong effect that suppressed calls by about 17 percent, that is a really large figure for a single event, and likely brought significant consequences for the neighborhoods most affected (think about what happens in neighborhoods where police can rarely solve violent-crime cases). And when the authors checked their call data against a few other high-profile police-violence incidents that occurred in Milwaukee and elsewhere in 2006, 2007, and 2009, they found some overall similar effects, albeit stronger ones for local cases.

All this suggests, unsurprisingly, that when people are given a reason to be scared or distrustful of the police, they’re less likely to call them for help. This, in turn, likely does a lot of societal damage: The absence of a functional relationship between police and a given community makes things harder for everybody, especially in areas with high levels of violent crime.

One interesting question is how the police-trust landscape has changed over time. Suffice it to say that things have changed dramatically since Frank Jude was brutally beaten in 2004, and even since the most recent incident covered in Desmond and his colleagues’ study. Today, everyone has cameras on their cell phones, and today, partially as a result of video after video of police violence directed at unarmed black people, we have Black Lives Matter. The viral news environment is also exponentially more hyperactive than it was just a few years ago — today, just about any incident with a witness will go national within a few hours. So it could be the case that in the post–Trayvon Martin, post–Tamir Rice era, now people are (unfortunately) used to these incidents and each one has less of an effect on their willingness to call the police.

But perhaps more likely, it could instead be the case that the sheer volume of coverage of police violence affecting black people has had an impact on African-Americans’ enthusiasm for engaging with the police all around the country, and that this will be a lasting effect with serious lingering consequences. You’d need a lot more data to be able to test this question, but the snapshot we have from Milwaukee isn’t particularly encouraging.