“How much gold makes an object vulgar?” muses text in the London exhibition The Vulgar: Fashion Redefined. On view now through February 5, 2017, at the Barbican, the exhibition scrutinizes the “territory of taste” with more than a pointed once-over. The gold in question is a luxe 1937 Elsa Schiaparelli evening ensemble with braiding reminiscent of ecclesiastics; in the exhibit, it is juxtaposed next to an opulent gilt-threaded fragment of a centuries-old chasuble (a vestment worn by a priest during mass).

Further on, Pam Hogg’s gold-lamé-draped catsuit or gold-fringed military epaulettes push the lines even more: What is the “right” taste, and what factors are at play in regulating it, as we throw around the judgment that we do?

Tackling the concept from many angles, the exhibit reminds us: “The vulgar is something we make. Nothing is naturally, or essentially, or in itself, vulgar … vulgarity, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder.” Taste is mutable, the notion of elegance evolves, and few are as breezily revisionist as designers, who constantly spin and overturn and outright flout written-off concepts with new élan.

Illustrated through a series of garments and installations, vulgar fashion is examined through its recurrent accusations: too trendy, too excessive, too sexualized, too exaggerated, too ostentatious. Is a logo a sign of prestige or tackiness?

There’s vulgar with outlandish scale, like 18th-century court mantua overskirts measuring over two meters in width, or Viktor & Rolf’s haute couture Emma ensemble, in which a voluminous baby-doll dress is paired with an oversize straw headpiece, or endless Galliano for Dior citations. There’s vulgar as the sexually explicit, like Vivienne Westwood’s “Eve” sheer body stocking (with strategically placed fig leaves in Perspex), or her “tits top” where the garments flaunt what’s below the fabric instead of hiding it, or Rudi Gernreich’s topless bathing costume from 1964.

There’s vulgar as overt copy and thus dilution of design, like a cheeky Maison Martin Margiela S/S 1996 evening dress whose sequins are nothing more than a faux glamour photocopied print (remade in 2012 for the H&M collab). There’s vulgar as referencing the ordinary, like Karl Lagerfeld integrating old-lady-style shopping trolleys for Chanel, or Hussein Chalayan’s dress replete with press-on nails. There’s vulgar as in-your-face kitsch like the Jeremy Scott pieces for Moschino devoted to McDonald’s, or the campy Bambi sweatshirt Riccardo Tisci created for Givenchy.

The Barbican’s film season dovetails with the exhibition, screening some self-deemed “good trash” like Fat Girl (by director Catherine Breillat), Southland Tales (Richard Kelly), Female Trouble (John Waters), and Boogie Nights (Paul Thomas Anderson).

With a wink of meta, the exhibition notes hierarchies within the museum that parallel those within fashion. The history of exhibiting garments rather than fine art was initially dismissed with indictments of vulgarity. Under Diana Vreeland and museum director Philippe de Montebello, an unprecedented Yves Saint Laurent exhibition at the Metropolitan was cause for scandal in 1983: According to the exhibit’s text, modern commerce passed itself off as art, tastelessly blurring “between the gallery and the department store.”

The vulgar is often confounded with the experimental, with pushing new boundaries. But especially for women, there is something deeper to fight against. A displayed edition of The Young Woman’s Companion (1841) chided ladies for “running a race for the acquisition of deformity” regarding new styles, and a 1920 etiquette guide demurred that “a lady is never so well-dressed as when you cannot remember what she wears.” Such pronouncements, bullying women into being discreet and inconspicuous, sartorially and otherwise, have not vanished. Regulating how women dress and patrolling their modesty is perhaps as much about their visibility and presence as it is about taste.

Society is, of course, constantly shifting the boundaries of what is appropriate: on the body, on the screen, in the museum. The Vulgar: Fashion Redefined encompasses a 500-year time frame, from the Renaissance to “the new baroque” of the 21st century. It shows the remarkable ways in which the parameters have changed, as well as the ways in which they continue to resist.

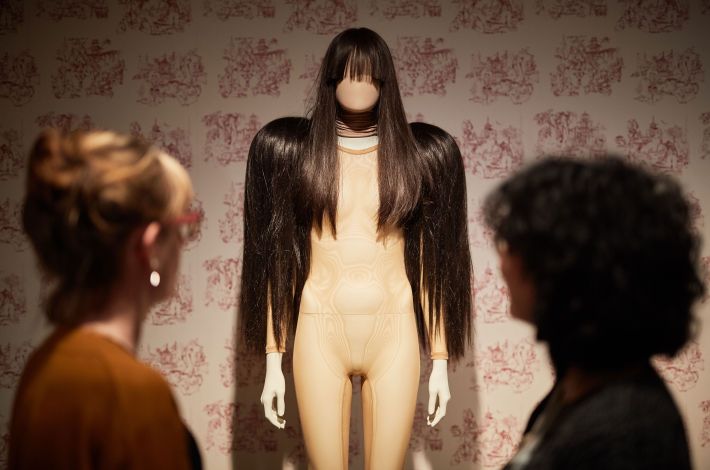

The Vulgar: Fashion Redefined Installation view Barbican Art Gallery, London On view through February 5, 2017

The Vulgar: Fashion Redefined Installation view Barbican Art Gallery, London On view through February 5, 2017

The Vulgar: Fashion Redefined Installation view Barbican Art Gallery, London On view through February 5, 2017

The Vulgar: Fashion Redefined Installation view Barbican Art Gallery, London On view through February 5, 2017

The Vulgar: Fashion Redefined Installation view Barbican Art Gallery, London On view through February 5, 2017

The Vulgar: Fashion Redefined Installation view Barbican Art Gallery, London On view through February 5, 2017

The Vulgar: Fashion Redefined Installation view Barbican Art Gallery, London On view through February 5, 2017

The Vulgar: Fashion Redefined Installation view Barbican Art Gallery, London On view through February 5, 2017

The Vulgar: Fashion Redefined Installation view Barbican Art Gallery, London On view through February 5, 2017

The Vulgar: Fashion Redefined Installation view Barbican Art Gallery, London On view through February 5, 2017