As I reflected on all the artists I saw at Art Basel this year, what struck me were how many talented female artists I came across. All told, Art Basel has about 25 fairs — including NADA, Scope, Pulse, and Design Miami — that give artists a platform to be seen on an international stage of editors, critics, and art lovers from all over the world. But no matter which fair I went to, I found myself continuously captivated by one female artist or another.

Some names I was already familiar with, like South African artist Tony Gum, whose Free da Gum series of photographs alludes to Frida Kahlo and touches on misogyny in the art world. Gum is single-handedly changing the definition of what people think a “millennial” African artist can be in terms of her subject matter and going against the grain of what’s expected from artists who are women of color. Then there’s Zoe Buckman, whose “Mostly It’s Just Uncomfortable” is a metaphor for attacks on Planned Parenthood, women’s dominion over their own bodies, and blocks to free sexual health care.

I was so moved by three women in particular — Tschabalala Self, Ayana Evans, and Chloe Wise — that I had to talk to them firsthand about the shifting balance of power at Art Basel (which for decades has largely been a man’s game). Here’s what they had to say.

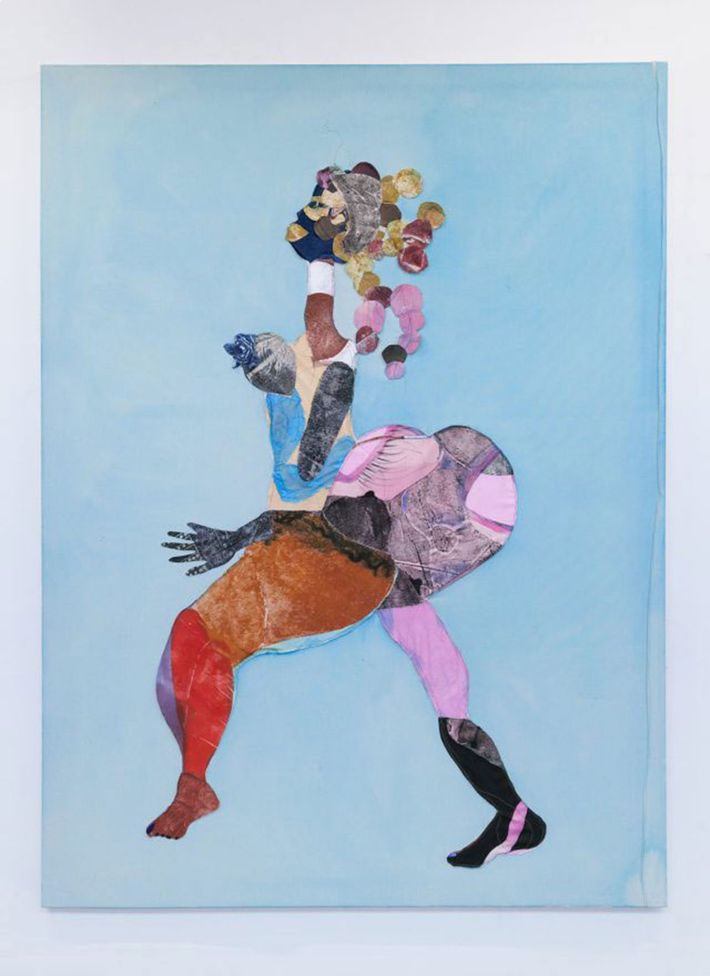

Tschabalala Self

Simply put, Self portrays the power of the black female body. The black woman is not an object in Self’s pieces — she is the focus, she is the protagonist, and she is an icon all on her own. Not to mention her four paintings sold out within minutes at NADA, with price tags ranging from $7,000 to $20,000.

“It’s very cathartic and validating for me to make this kind of work,” Self says. The kind of work she refers to centers on the black woman’s experience and nothing else. There are so many layers that define being a woman of color in today’s society, and in a way Self’s work sets all those preconceived notions free. It’s less about what it means to be “woke” and more about understanding what it means to walk around in a black woman’s body in 2016.

“My work is a reimagining of the black female body by a black woman; and it’s a reimagining of femininity through a context in which I speak truthfully about what it feels like to be a woman, and not how other people feel being a woman is like. It’s not a reactionary perspective — my characters exist within themselves — they don’t react to misogyny, or racism, they’re just trying to find their own inner peace and center and exist within that. It’s feminist art for women, but it’s also black art for black people.”

Chloe Wise

Canadian artist Wise is a multidisciplinary artist who creates paintings, videos, and sculptures exploring feminism, consumerism, food, and what she calls “art about the history of art” in a satirical way. Her Prada-stamped bread-bag piece Ain’t No Challah Back (pack) was all the talk at NADA last year, but this year she was selling her first monograph, Chloe Wise. The book depicts a body of work created over the past two years, including her infamous painting Life’s Rough, But Not Rough Enough, and takes on still life, seduction, and bondage.

“Every single second of my life is about creating work,” says Wise. “In this predominantly male art world, to be able to claim space as a female is something that you have to be really forceful and adamant about.”

“There is still so much inequality in pay, prestige, and acceptance of female artists,” Wise continues. “I have the shows and respect and collector base and I’m not complaining, but if a man made this stuff, it would be in museums with people saying holy shit. Male artists can get away with doing so little and have it mean so much. I do feel optimistic though. It’s my duty and the duty of my peers to make work that’s so good you can’t ignore us.”

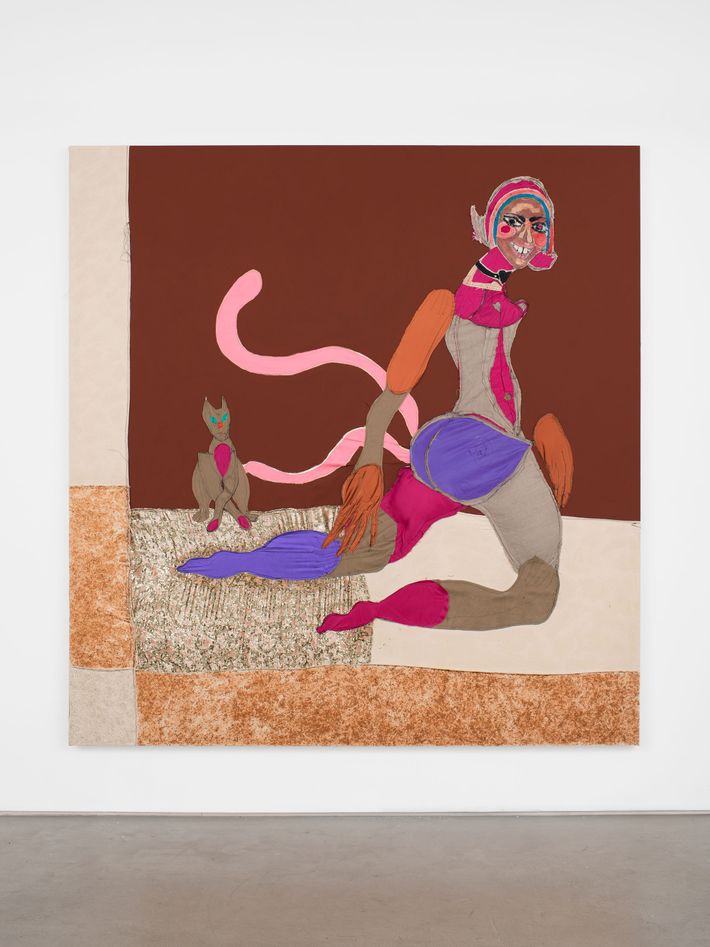

Ayana Evans

As a performance artist, Evans approaches what it means to be a woman with complete honesty. Pieces like I Just Came Here To Find A Husband explore her struggle with being single and finding peace within herself, while Frying Chicken depicts her insecurities about blackness, showing her in heels, eating fried chicken with baby oil and chicken grease all over her body. Her feminist performance, Girl, I’d Drink Your Bath Water riffs on a popular catcall, in which she used a bathtub, water, and soap to cleanse herself.

Her most popular body of work, Operation Catsuit, started when Evans was mocked for wearing a neon-green catsuit to art events, yet accepted when she wore the appropriate “artsy look.” “My body was fully covered but because of my curvy shape, the outfit was controversial,” Evans says.

Watching her perform with such physicality, and touch on emotional and political issues, sheds light on the significance of the black body, as well as having pride in your body.