At the moment, many Americans view Arabs and Muslims with fear and disgust. There has been, by many metrics, an unfortunate uptick in such sentiments since the 9/11 terror attacks. Perhaps the clearest indicator of public opinion on this came after then-candidate Donald Trump proposed a temporary total ban on Muslims entering the United States — something like a third of Americans said they agreed with this very hard-line proposal (it varied from poll to poll).

As Brian Resnick explains in an interesting article in Vox, these sorts of feelings are intimately connected with the psychological phenomenon of dehumanization, or not seeing certain groups of people as fully human. Many people who dislike Muslim and other groups view them as not quite members of the same species. Social psychology has long identified this as a key variable in how tension, armed conflict, and even genocide can metastasize. There’s a reason why, as Resnick puts it, the Nazi film “The Eternal Jew depicted Jews as rats… [and during] the Rwandan genocide, Hutu officials called Tutsis ‘cockroaches’ that needed to be cleared out.”

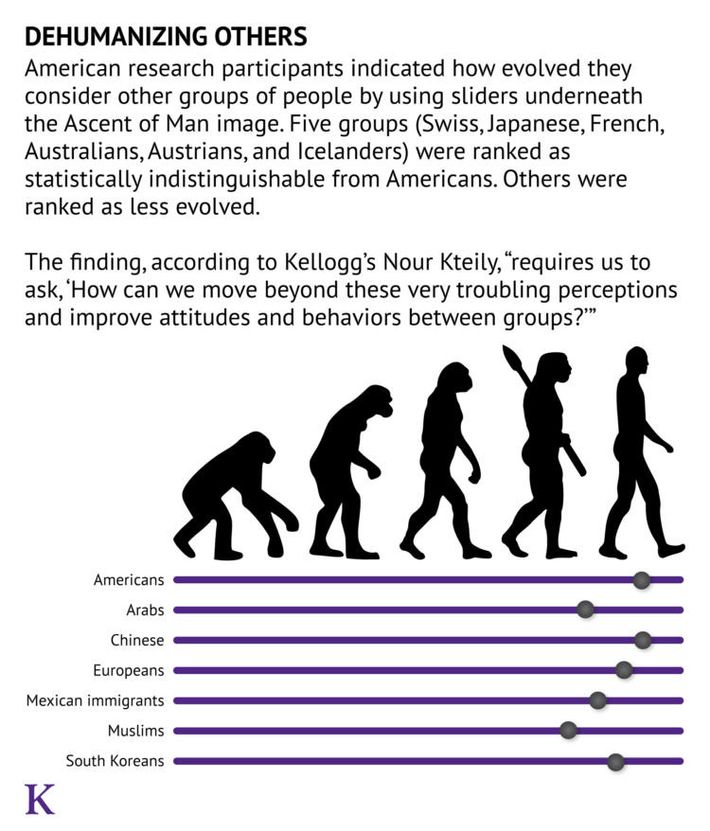

Some researchers have honed in on this phenomenon, and Resnick’s article is mostly a profile of Nour Kteily, a Northwestern University psychologist based at the Kellogg School of Management who is a leading expert on the psychology of dehumanization. One of Kteily’s most interesting and important innovations is a tool that gauge’s people’s tendency to engage in dehumanization by … simply asking them the question directly. Respondents use a slider and classic “ascent of man” imagery to gauge how human they view different groups as, as this graphic from an article published by Kellogg explains:

There’s an interesting contrast here between Kteily’s ascent-of-man tool and the most popular current means of evaluating racism in social psychology, the implicit association test (IAT). Not to overstretch the comparison, since the two tools are geared at measuring different things, but the IAT (which I have argued is riddled with all sorts of problems) assumes the best way to capture meaningful bias is to effectively “trick” people into revealing it, while Kteily appears to think you can get a solid-enough view of the landscape by asking people to cop to racist beliefs outright. And his research shows that people dehumanize Arabs and Muslims more than other groups.

Respondents’ tendencies to exhibit this form of “blatant discrimination,” as Kteily calls it, appear to be correlated with certain political preferences. In one Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin study he co-authored with Emile Bruneau, for example, Resnick writes that “blatant dehumanization of Muslims and Mexican immigrants was strongly correlated with Trump support — even when compared with support for other Republican candidates. The data is ‘consistent with the idea that support for some of the Republican candidates (and Trump in particular) comes not despite their dehumanizing rhetoric but in part because of it,’ Kteily and Bruneau conclude[.]”

After laying out some more details about the ramifications of dehumanization, and arguing that the dehumanization of Muslims is getting worse, Resnick briefly touches on the question of what can be done to address dehumanization when it pops up. One approach is to try to short-circuit the belief many people have that members of the dehumanized group hate them and want to harm them. “In a study, Kteily and Bruneau created a fake Boston Globe article that highlighted [research showing that many Muslims around the world view Americans positively]. When mostly white participants read that Muslims actually admired Americans, they didn’t dehumanize them as much on the Ascent scale.”

But the bigger, more effective approach is also more difficult. “Overall, the experts I spoke to all said that the No. 1 way to combat dehumanization is also, frustratingly, one of the hardest to accomplish: simply getting to know people who are different from us,” writes Resnick. “It’s hard because we have many opportunities — via the news and social media — to get the thin-slice exposure to unfamiliar groups that activates the us-versus-them program in our brains. And we have so few opportunities to do the hard work of breaking through those first impressions and getting to know the human soul inside.”

Here Resnick is referring to a decades-long body of research on the so-called contact hypothesis, which suggests that meaningful intergroup interactions can mitigate some of the worst excesses of our in-group/out-group cognitive programming. As he rightly points out, this isn’t easy — no one suggests it is — but when it’s pulled off successfully, it does seem to be a reliable way to get people to view one another as human beings.