Before the International Center of Photography’s current exhibition closes May 7, one room, titled “Black Lives (Have Always) Mattered,” is worth a visit. It showcases vintage portraits of ordinary people who used photography as a means for protest — hairdressers, nurses, educators, and activist leaders. Each frame traces a photographic history of black activism, from emancipation and reconstruction to the civil-rights era and the Black Lives Matter movement.

Curated by Kalia Brooks, the collection is part of ICP’s ambitious, sprawling show “Perpetual Revolution: The Image and Social Change,” which examines a number of global crises through the lens of visual culture, including climate change, the refugee crisis, transgender rights, police brutality, and the rise of white nationalism. With “Black Lives (Have Always) Mattered,” Brooks aimed to extend the legacy of the civil-rights movement beyond the 1950s and ‘60s, when it’s traditionally thought to have started. She explained that as far back as the late 19th century, when photography was invented, cameras were vital in black Americans’ fight to be recognized. She said black women in particular used photography as a “subversive means of imaging” themselves.

“Being able to image oneself is a political act,” Brooks told the Cut. “It shifts our understanding of who has the authority to represent someone.” Frederick Douglass, the most photographed man of the 19th century, “understood that to get his portrait taken was to really undercut a lot of the racist stereotypes of black people in America, like images of black face or caricatures of black people in minstrel shows,” she explained. Sojourner Truth also “used photography as a political tool for abolitionist purposes.”

In excavating photos from the ICP’s archive, Brooks found advertisements for camera equipment and scenes from the court-ordered integration of a school in Little Rock, Arkansas; other images were photos commissioned by Life magazine, or family studio portraits. “A lot of these women are anonymous, unidentified women,” she said, while others, like Myrlie Evers-Williams, are civil-rights activists who left an indelible mark on American history.

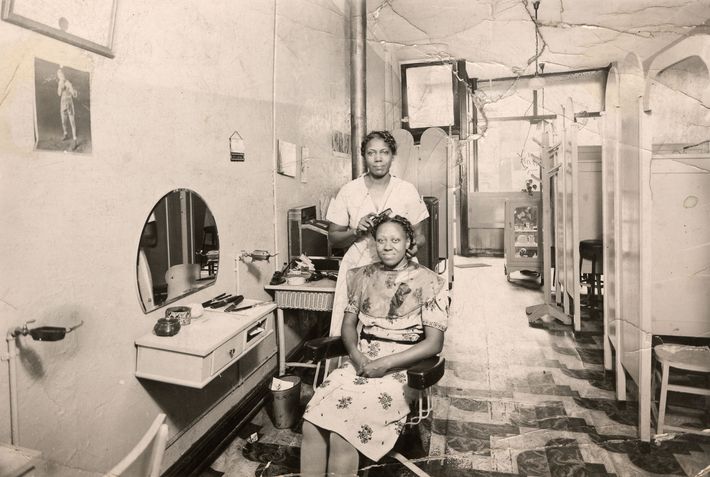

In one particularly striking photo, two unidentified women gaze peacefully at the camera in a hair salon. Brooks noted that many of the first black female entrepreneurs owned beauty parlors. “It was a massive emancipatory industry to be involved in,” and often provided key spaces for mobilizing efforts, she said. Other photos depict upward mobility in black communities, showing stylishly dressed women toting accessories that signaled wealth.

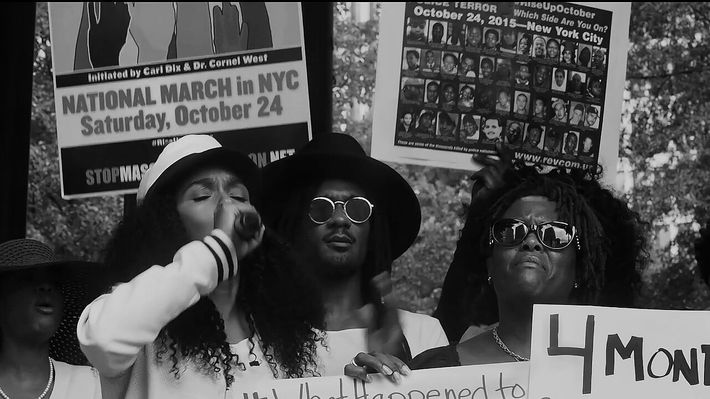

Across from the room’s salon-style wall of photographs, video installations created by contemporary artists show Black Lives Matter protests in Atlanta, Baltimore, and Washington, D.C. Nearby, a row of vintage TVs blares breaking-news video footage of the militarized police force in Ferguson after the fatal shooting of Michael Brown. The scenes demonstrate the success of the Black Lives Matter movement — founded in 2013 by Alicia Garza, Opal Tometi, and Patrisse Cullors — in mobilizing communities to stand up and speak out against police violence.

The showcase closes with Sarah White’s video Raising Black Joy, which captures a little girl dancing on her front lawn. “The ability to generate, express, cultivate, and nurture joy in the midst of trauma is hugely important,” Brooks said. “Joy has been a necessary form of expression for black people, in relation to the amount of just social, cultural, and political pressure black populations have had to respond to — and have been able to flourish, in spite of.”

Click ahead to see photos of women featured in the exhibition, with stories behind each portrait.

A large hand-colored portrait of a photographer holding a bulky Speed Graphic, the camera of choice for news photographers in the 1930s. It’s likely an advertisement for a photographer’s studio or a new product.

The actress-singer Minnie Brown, captured by Luther S. White, a bar owner and businessman who photographed fixtures of 20th-century Broadway — both onstage and off.

Beauty parlors allowed many black women to become financially independent entrepreneurs. It was, according to curator Kalia Brooks, “a massive emancipatory industry.”

Two residents of Los Angeles, photographed in 1900.

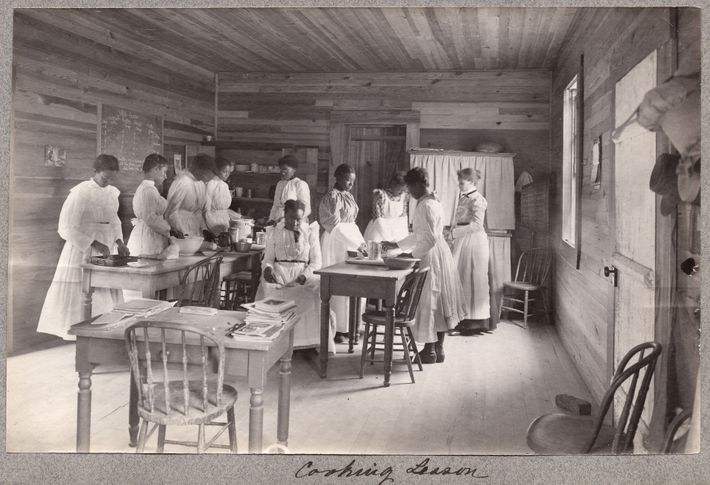

The Calhoun School was founded by Mabel Wilhelmina Dillingham and Charlotte Rogers Thorn during the reconstruction period. It provided basic educational and vocational training to black communities living in Lowndes County, Alabama. This photo was likely commissioned by Booker T. Washington, who founded the Tuskegee Institute.

This video draws a visual correlation between activism of the Jim Crow era and the new civil-rights movement, weaving together pop-culture references with film from protests in Atlanta, Ferguson, and Baltimore. The piece includes commentary from various perspectives on the strategy of black liberation.

A still from Sarah White’s ten-minute video Raising Black Joy, of a little girl dancing on her front lawn. The video embodies what Brooks calls “the redemptive moment” — of joy as representative of resilience.