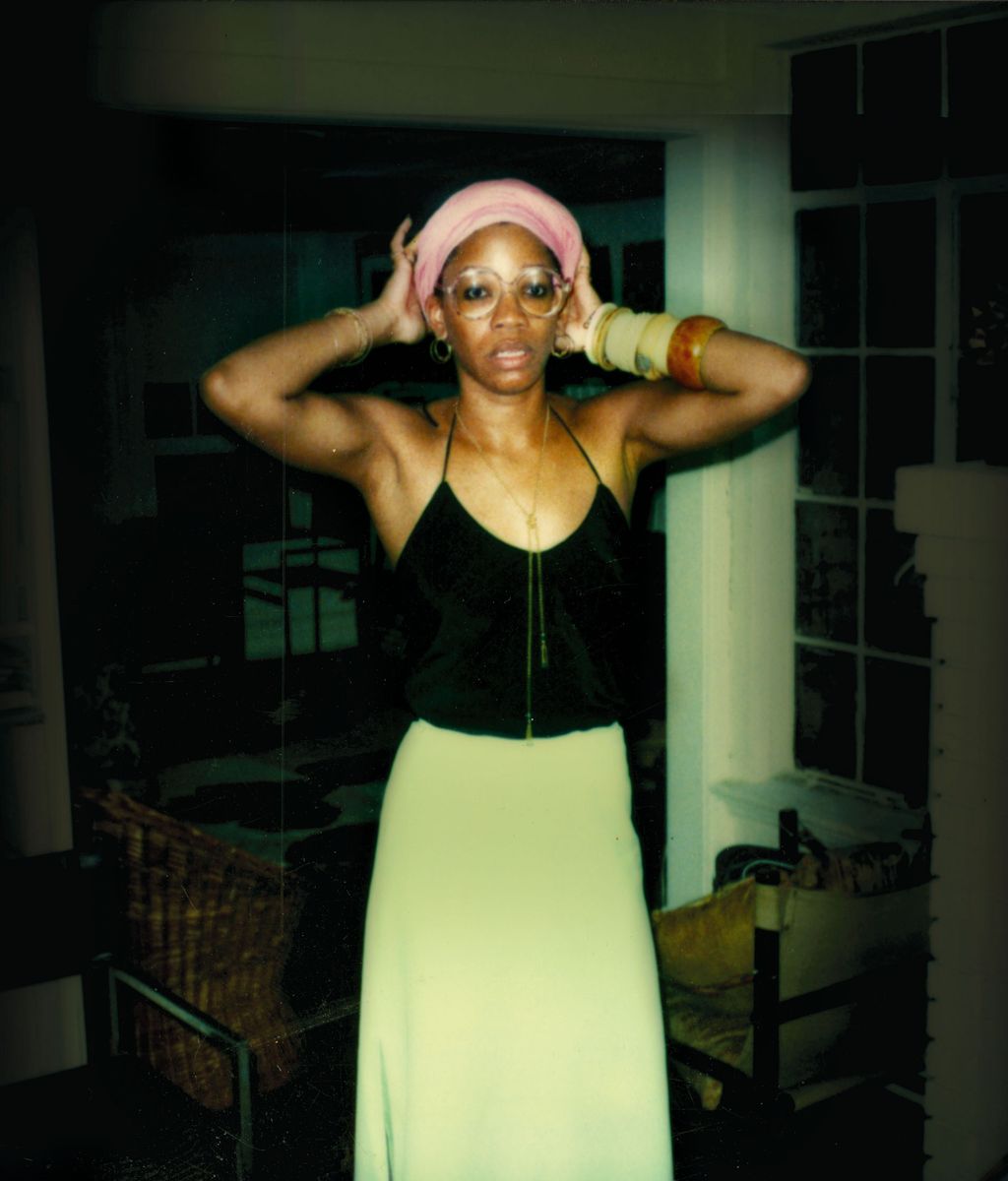

Before Jessica B. Harris launched her career as an expert on the food of the African diaspora, she was a young teacher and up-and-coming writer surrounded by some of the most famous creative minds of the ‘70s and ‘80s. “I’m not a bold-faced name,” she said while petting one of her Siamese cats at her house in Brooklyn earlier this month. “I’m aware that they were bold-faced names, but they weren’t in my life because they were bold-faced names. They were in my life because they were people I knew.”

The people Harris was talking about — James Baldwin, Maya Angelou, Toni Morrison, Nina Simone — figure prominently in her new book, My Soul Looks Back, a memoir about her life writing, editing, and eating in the West Village in the ‘70s. The book, out this week, is Harris’s 13th and follows a series of critically acclaimed cookbooks and culinary histories that catalogue everything from Creole flavors to African cuisine’s many mutations in America. Harris’s memoir tells her story of growing up black and middle-class in New York City, recounts her years-long relationship with Sam Floyd (James Baldwin’s best friend, who eventually died of AIDS), and examines why the West Village and the Upper West Side were homes to members of the black intelligentsia during that time. It also features a version of Maya Angelou’s recipe for “eight-boy curry.”

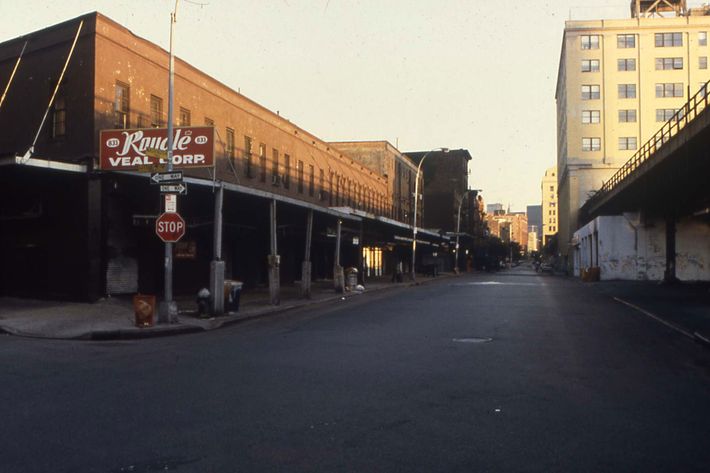

Ahead of the launch of My Soul Looks Black, Harris took me on a walking tour of her old New York City haunts: from the Pink Tea Cup, a legendary soul-food restaurant that closed in 2010 then reopened with a new owner in 2013, to St. Vincent’s Hospital, where Sam, and many others, died. On her first time back to explore the West Village streets where she came of age, Harris shared stories of parties inside Sam’s apartment, the most memorable dishes from El Faro’s — caldo gallego, a sausage-and-kale soup with collard greens and potatoes — and what it felt like to be a young observer among the foremost black creative minds of the time period.

On “Club 81,” where all the biggest names met:

“I was in Sam’s apartment at 81 Horatio Street (or, as I call it in the book, ‘Club 81’) with Stokely Carmichael, I was in there with James Baldwin on more than one occasion, I was in there with Martina Arroyo. Louise Meriwether was there. Mary Painter was there. Sam did much of the cooking. He ruled his domain. He did roast goose, he made turnip greens with the turnips in them. He was a good cook. Or if he wasn’t cooking, someone would go pick up food from El Faro’s, what I’m told was the first Spanish restaurant in New York City, down the street.

“Sam and I had met as teachers in the SEEK program at Queens College and we began dating after a few months of seeing each other. That’s when I entered this world. We shared a love of cooking, travel, intellectual pursuits, and entertaining. I learned a lot of bar etiquette from him. Sit down at a bar, order your drink, put money on the bar: that lets them know to run a tab, or tells them that you want to drink until that cash runs out. Back then, the Waverly Inn had a pre-theater dinner between 5:30 and 6:15 or something like that. It was $5.95.”

On the power of literary friendships:

“Sam and I went to France and we spent some time with Baldwin at his house there. He read a draft of If Beale Street Could Talk aloud to us one night. It was astounding, astonishing, amazing, exactly as you would expect it to be for somebody who was in their 20, sitting at the foot of the master while he reads. It was extraordinary. He read it twice in the space of my stay there. The second time, Toni Morrison was there.

“They were friends. They understood each other and they trusted each other. Having somebody read your unedited stuff, or reading it to them, is a leap of faith, and it requires extraordinary trust. That he would ask me for my feedback on the draft was one thing. It was another level, another kind of thing. I don’t think he was talking down to me, but he was asking me for something that I was unable to understand or explain. I wasn’t at that level yet–I was still young and in awe of him. I think that there was a level of trust, a totally different level of confidence and love in reading it to someone who is an equal. I think that was the relationship that Baldwin and Morrison had. She is, I have to come to learn, one of the few people he had that with. She could talk to him as an editor because she was one. Sam and Jimmy were best friends, so that’s another kind of thing. It’s not necessarily that he was speaking as an editor, he was speaking as a friend who absolutely trusted.”

On close encounters with Nina Simone:

“Everybody wants to me to say something about Nina Simone calling me ‘the bitch in the red dress,’ which happened the first time she saw me across the room at a party. Those were the first words she ever said about me, and from then on, we were in and out of each other’s orbits. We now know, which we didn’t before, from the film about her life, that she was bipolar. If you don’t know this about yourself, if no one else knows about you, you just come off as volatile, and she was that.

“When I saw her in Abidjan in Côte d’Ivoire, the same thing happened. Something went wrong and she snapped. I was walking by the hotel she was staying at and I heard a raised voice and thought, ‘Oh my gosh, somebody is speaking in English, maybe I can help.’ I walked in and it was [Nina]. The argument was resolved and I introduced her to the hotel manager, and he soon gave her access to all the coveted private amenities at the hotel. He was a little in awe of her.

“We spent two days together in Abidjan in the ‘70s, or maybe it was the late ‘80s. I was traveling for work, as I was doing quite a bit back then. Nina was such a towering talent, of course, but it was an exhausting few days. At one point, she joined me by the pool, and after disrobing into a white bikini, she looked at me and said, ‘I’m older than you are, and my body’s better than yours!’”

On the Upper West Side versus the West Village:

“The buildings were taller, the people were different. There was perhaps an edginess to the West Side that may not have existed in the same way in the part of the Village that I lived in. It certainly existed in other parts of the Village. There was a nucleus of black folk on the West Side that didn’t exist in the same way in the West Village. A lot of the people who were in the black arts crowd, if you will, were on the West Side.

“There was a big scene. It was music, it was dining. It was socializing. A lot of people went to the West Side just to get their hair done. The most memorable thing for me was seeing Al Green singing, right across from me, in a cabaret setting at a taping for Ellis Haizlip’s show on PBS. The places I ate at were the Cellar, the Only Child which is further downtown, and Two Steps Down. They were black-owned, so it was very different than in the West Village. There were all kinds of different places. Two black-owned restaurants downtown at the time were the Pink Tea Cup in the West Village and Princess Pamela’s in the East Village.”

On the AIDS epidemic hitting the Village:

“I remember Vertamae Smart-Grosvenor, another culinary historian, once sat me down and had me go through every picture she had of people we knew during this time and made sure I knew who was who in every single picture she showed me. ‘Because you are going to be the one who writes about it.’ That was scary. It was horrific. Particularly for someone who worked in, loved, and lived with the arts. You lost all your friends. Or certainly a large number of them.

“When you’re the youngest, you tend to outlive people. It was horrible. The way people were treated was horrible. In ways you can’t even think of today. Some people were extraordinary under pressure and some people were hideous. It was a transformational moment in the city and its history and that’s part of the importance of St. Vincent’s, which is why it’s astounding to me that it is now a condo. It was such an important place — it was the epicenter of what was a horrific time period.”

On witnessing the end of an era:

“It’s my life. I lived it. I live somewhere between Frank Sinatra and Édith Piaf. I don’t regret Sam and what happened with him. I don’t regret my youth. The road not taken is the road not taken. Do we need to dwell on it? You didn’t take it. So get on with it.

“I think Maya’s dying made me want to put all of this into context. It also made me realize how extraordinary it all really was. When she died, I wrote an article for the New York Times about cooking with her. I had done that for four decades. I’d certainly known her over four decades. I am massively influenced by the time I spent with them. As I’ve aged I’ve developed a large aura, if you will. I grew up with a certain kind of entertaining, a certain way of being, from my parents. And if anything, these people were like finishing school.

“Remember when icons could preach and boogie? I think that’s an important thing. Yes, they were icons. Yes, they transformed the world for all of us. But they could also hang out, and suck some Scotch down. It’s important to know that they had that. They had that with each other. They were a tribe. They read each other’s stuff. They sustained each other. They did amazing things together. They were my tribe, too, but now they’re gone.”