Most people tend to have a certain idea about their heritage: that they simply are, well, whatever they are. Scottish or German or Nigerian or whatever else. Maybe there’s some other stuff mixed in there, sure, but most people have a sense that they’re “from” one particular place, and that’s where their culture — and maybe some of their values — originates.

Naturally, DNA tells a more complicated story, and a new article in Science by Ann Gibbons very usefully punctures a bunch of myths, some of them pretty harmful, about human ancestry. The vast majority of us are mutts, it turns out, and oftentimes the genetic heritage we think we have bears little resemblance to what’s actually hiding in our chromosomes.

Gibbons starts the article by quoting a German neo-Nazi, doing what neo-Nazis tend to do, expressing alarm about the arrival of Syrian refugees and the prospect of them sullying his precious German genetic heritage.

From there she swiftly moves to the main point of the article:

In fact, the German people have no unique genetic heritage to protect. They—and all other Europeans—are already a mishmash, the children of repeated ancient migrations, according to scientists who study ancient human origins. New studies show that almost all indigenous Europeans descend from at least three major migrations in the past 15,000 years, including two from the Middle East. Those migrants swept across Europe, mingled with previous immigrants, and then remixed to create the peoples of today.

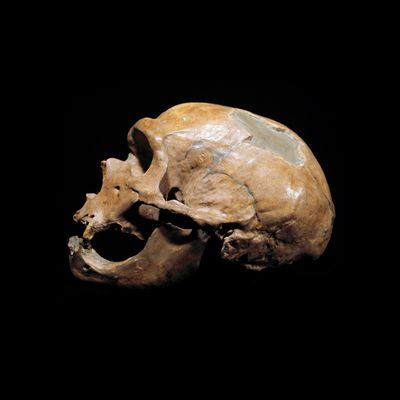

Using revolutionary new methods to analyze DNA and the isotopes found in bones and teeth, scientists are exposing the tangled roots of peoples around the world, as varied as Germans, ancient Philistines, and Kashmiris. Few of us are actually the direct descendants of the ancient skeletons found in our backyards or historic homelands. Only a handful of groups today, such as Australian Aborigines, have deep bloodlines untainted by mixing with immigrants.

That aforementioned notion of German purity, to take one example, comes from a Nazi mangling of an already somewhat thinly sourced story about a Germanic fighter named Arminius who supposedly led a rebellion against the Romans 2,000 years ago — the Nazis portrayed him as a blond-haired member of a supposed master race.

Now, it shouldn’t be surprising that Nazis don’t have a particularly sophisticated grip on genetics. But this article is still an interesting, comprehensive look at where researchers are in their quest to understand humanity’s genetic legacy. And the short, also-unsurprising answer is: We’ve moved around a lot and mixed it up a lot.

Gibbons’s piece also usefully complicates the notion of genetic “superiority,” highlighting just how historically contingent this idea is. For example, she writes of two different groups that collided at one point and produced offspring: “The unions between the Yamnaya and the descendants of Anatolian farmers catalyzed the creation of the famous Corded Ware culture, known for its distinctive pottery impressed with cordlike patterns … According to DNA analysis, those people may have inherited Yamnaya genes that made them taller; they may also have had a then-rare mutation that enabled them to digest lactose in milk, which quickly spread … It was a winning combination. The Corded Ware people had many offspring who spread rapidly across Europe.” Today, of course, very few people are aware of the Corded Ware culture — a group that was very much, for random genetic reasons, in the right place at the right time.

For most of human history, humans haven’t been great at recording history accurately, so along the way many cultures have developed myths about their lineage, about who was where, when. A lot of the time, the straightforward stories people tell to be proud of themselves and their ancestors are oversimplifications, at best. In the worst cases, these myths lead to ideologies like nationalism.

It’s important to understand the appeal and functional role of bloodline myths, of course: “This group could sully our bloodlines” packs a bit more of a visceral punch than “I am nervous this new group will cause the neighborhood to change.” Because people don’t tend to really understand genetics, and because the subject efficiently taps into many people’s most intimate feelings about disgust and purity, such talk can be a useful way to rile people up, almost always for the worse. Which is why it’s important to understand just how superficial it really is.