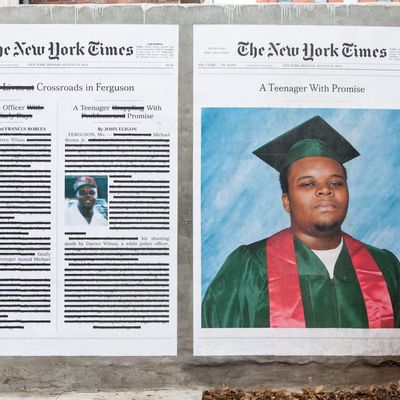

Alexandra Bell wants you to think twice about what you read. Over the past two months, the 34-year-old Brooklyn artist has been transforming New York Times articles that she sees as loaded with racial prejudice — rewriting headlines, redacting text — to illustrate the inherent bias in news media. The result is a series of images posted across Brooklyn buildings and on the walls of subway stations. In one of her works, Bell, who has a journalism degree from Columbia University, takes a 2014 article about Michael Brown, an unarmed teenager killed by a police officer, originally titled “A Teenager Grappling With Problems and Promise,” and changes it to read “A Teenager With Promise.” In another, she takes articles about the Ryan Lochte robbery in Brazil and the culprit of a hate crime and rewrites the headlines to identify the criminals as “white-Americans.” In all of her pieces, Bell’s art forces us to consider how decisions to tell the stories of black lives are made. We spoke with Bell about the message behind her work, what she makes of the current “fake news” crisis, and the perils of making art for public spaces.

Why did you pick the New York Times profiles of Michael Brown and Darren Wilson to use in your first work of art?

Journalists are taught to be objective and not to advocate for people or causes. I’m really interested in these moments where papers, especially the more liberal-leaning papers that we’re inclined to trust more, make sort of hiccups on that principle.

I also think people who are enduring abuses [of power] in the world deserve at least from my art to be able to look at the paper and see themselves as full people, and I don’t think that’s the case oftentimes with black people.

You decided to edit and redact these stories instead of writing or creating new versions. Why is that?

I’m saying not saying that none of this information [in the New York Times’ story] is pertinent, obviously this story should be here on some level, but I’m revealing another point of view that isn’t often considered. That’s what a counter narrative is. I also want to show how these little tiny changes tip the scale, and can fully change perspectives.

In your other two works, you explore the idea of actually identifying white people as “white-Americans” in the media. Why take this approach?

There’s so much inherent ownership in the way people talk about white people and land and space. So, when I see races in headlines and then I see something as blasé as “Tulsa Man Accused of Harassing Lebanese Family Is Charged With Murder,” there’s something very arrogant about that. I wanted him to be a white-American, I wanted to stop this situation where we look at white people as this invisible norm and everyone else bares the burden of race and race labeling in this way that I think is why we have these crimes in the first place.

Let’s talk about this era of “fake news” that we’re in. What has been your reaction to that?

We’ve always had fake news. I’ve read a lot of books about news values and from them you get a sense of how the newspaper was always the way to discriminate. They had ads looking for runaway slaves, papers published to sell slaves, they wrote about lynchings in this surprisingly respectable way, some papers before they were delivered to black neighborhoods had the financial sections removed. Everybody is up in arms about fake news stories, but let’s talk about reputable papers that contributed to the criminalization of black people post-slavery and helped to uphold white supremacy. I’m not impressed or shocked by the fake news, this is old and this is actually very minor in comparison to what I’ve seen and read in my studies.

One risk in public art is vandalism. In your case a lot of racist things have been written on your Michael Brown works. Was that something that you expected?

[When I was putting this together], I was like should I use Mike Brown’s face? I don’t know him and even if I did I don’t want people to be in public and be revictimized. I’m not putting him up in a negative way, but there is violence happening to him — like someone writing “nigger” on his face. What I’ve learned is that people are really invested in this narrative. It’s such an atypical narrative for people to see a black kid in the paper a positive way, it’s too much for people. The only way for them to reconcile it is to write “nigger” or “thug” on his face, because that’s what they’re used to. I’ve also had so many people write me like, “This has been so healing.” I think it’s healing because we don’t often see ourselves represented as full people.

How can journalists address their racial bias?

It’s important [for journalists] to try to consider a person’s life and humanize them, but my problem is their starting point. What does it mean when you go into a situation already thinking more negatively toward a group of people? How do you make up for that difference? I’m not saying that you just need to put a bunch of black people in the newsroom and they’ll know better because some black people are prone to make the same mistakes, though I do think newsrooms need to be diversified.

I think the Ryan Lochte one is a good example of what I feel like is this natural instinct to shield white people when they do bad things. The decision to have a photo of Usain Bolt on the front of that paper [under the headline for Ryan Lochte’s robbery], I just found incredibly problematic. They could have put a photo of those four guys there. There are moments like that where I see things that are frustrating to me because I feel like there is an opportunity to level the field a little.

I’m not saying I hate journalism and I hate news media, I’m just saying that we’ve been in this country for hundreds of years and for a good chunk of those, folks were slaves and didn’t have rights, and it’s not like there were tons of investigative pieces trying to put that to an end, [the news media] was pushing it along.