On Monday, the abrupt announcement of beloved editor Robbie Myers’s departure from Elle magazine shook up a New York Fashion Week season that was already on unsure footing. From the start, there was much ado about Fashion Week being “over” as we know it, as well as thick, glossy magazines being “irrelevant,” with the next generation interested only in easily digestible, digital content. So, the news of Myers’s exit compounded with Graydon Carter leaving Vanity Fair and rumors of Glenda Bailey leaving Harper’s Bazaar had many crying “End of days!”

And then on Thursday morning, the day after New York Fashion Week ended, the Times broke that Glamour editor-in-chief Cindi Leive was stepping down, too. This wasn’t the end; it was a “changing of the guard,” and the future looked bleak.

As the Cut fashion critic Cathy Horyn pointed out in her decidedly optimistic essay prior to Fashion Week: “Someone in New York is always complaining about fashion.” But this season felt particularly upsetting because people weren’t just flippant; some of them were scared for their future. What was going to happen to a business that those like Myers, Carter, and Leive spent decades building? How could it possibly continue, with no one left with any “real” experience to lead it? Was the figure of the “magazine editor” dead, too? And what would it look like then if Instagram influencers ruled the world?

These questions and concerns are not unfounded — making a print magazine is a very specific, and increasingly scarce skill set. “Brands” have a choke hold on the industry right now and social media-sameness is rampant. There’s clearly some form of a “crisis” happening in fashion right now. But I deeply resent the assumption that the next generation won’t ever be up to the task, which I feel is being generally implied. As doomsday responses to Carter, Myers, and Leive’s exit began to flood my social media feeds, my sympathy and sadness quickly turned to frustration. There I was, working marathon days during New York Fashion Week, only to be told that as a member of the younger generation, I didn’t care just as much about what this industry was in order to continue to make it great.

I’ve heard it all before: The job I dream of having when I’m 40 years old probably isn’t going to exist, or I will need 100 million followers to get it. I’m just another internet-obsessed millennial more concerned with front-row celebrity-selfies and fidget spinners than long-form journalism. I broke something great, and I don’t know to fix it. Or I’m too scared to. I’m part of the problem. The ship has sailed and the golden days are gone.

But I refuse to believe this! I too grew up reading and collecting print magazines; and I am just as eager to learn about how an amazing, beautiful, meaty story gets made. I love photography and heart-stopping design. I want to see my byline above a well-reported story more than I want to be verified on Twitter. I want to develop sources — even if they’re in my Instagram DMs — and break news without being afraid of offending brands. Sure, I may not have the experience yet; and the future may not be on a printed page, nor look the way we all want it to. But my standards and enthusiasm are just as high. I feel like screaming, “Teach us, don’t subtweet us!”

In hindsight, I fully admit that it is the most millennial thing ever to make these editors’ departures about me. And maybe I’m being naïve about the future; maybe things really are as bad as everyone says they are. Of course, if I was one of the many talented people being laid off after decades of hard work in favor of someone younger and cheaper who does good Instagrams, I’d be pissed off, too. And of course, on the flip side, I’m lucky to be working for a company that supports me and understands how things should be integrated. I’ve also gathered a set of great mentors who want to see me succeed; who will pick up my frantic phone calls asking for feedback, or who will respond to my whiny Slack rants with gentle guidance.

That being said, I would still argue that my knee-jerk reaction was indicative of a more general attitude that’s resulted from younger, digital natives being pitted against canonized print-media legends, and vice versa. We’re told that we’re adversaries, when in fact we need to learn from each other. And I blame corporate structures in general for this culture, not Twitter. Unfortunately, most of the bigger, traditional fashion-media companies (and yes, a bit of lingering snobbery) have made it so that digital and print mostly still run in their own lanes, yet compete for the same resources — and everybody suffers as a result. Leaders are either being pushed out or jumping ship. And the next generation isn’t being given any incentive to stick around and actually learn something.

I’m not saying that fashion has ever been warm and inviting, or asking for hand-holding or pity. Rather, that as the world changes so rapidly around us, all of us would benefit from more conversations about how to make great fashion editorials. Those still in power at big media conglomerates need to work harder at keeping experienced talent around for longer, so that younger talent can learn from them. (And no, I don’t mean fake HR “mentorship” programs that never happen.) If the big publishing houses want their magazines to survive, print and digital need to be collaborating side-by-side in an organic way so that each feels personally responsible for the success of the other. In order for this to work though, corporate leadership also needs to create an environment that doesn’t put a price tag on “new,” quick ideas, rendering “old,” more time-consuming ones moot. Those stuck in the middle also need to be given more support. And finally, media conglomerates need to make it so that getting more involved with either side — print or digital — doesn’t mean adding more work to one’s already overflowing plate. “Integration” shouldn’t have to happen on the weekends, or when everyone else has already clocked out.

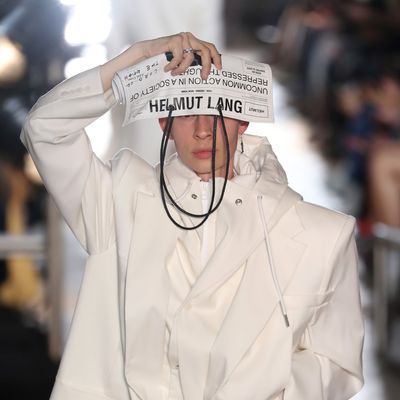

As New York Fashion Week comes to a close once more, I think we can all agree that Cathy Horyn was, as usual, correct: Things are not as they once were, but everything is also going to be fine. The greats are still great, and a handful of young designers are on the right path — they just need to keep digging and daring, and more importantly, carving their own path. (This goes for editors, too.) Laura Kim and Fernando Garcia carried the torch nicely at Oscar de la Renta; Alexander Wang, Mike Eckhaus, and Zoe Latta all brought life to a dead-end street in Brooklyn; and one of the most energizing nights of the week was on Monday at the Helmut Lang show, where Shayne Oliver and Isabella Burley were tasked with reviving the ’90s brand once more.

I was born in 1992, so needless to say, I knew as much about the original Helmut Lang as Lil Yachty, who sat front row. (A lot more than Diplo, though. That’s for sure.) But what I learned that night is that the people who come before us set the bar high on purpose. We’ll get there, wherever “there” ends up being.