When you think of major, contemporary fashion exhibitions in America, the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is the archetype. Ever since its blockbuster Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty show in 2011, (and the involvement of Vogue’s Anna Wintour, who now has her name on the wall) the Met has set both the tone and the standard for shows of this nature. Celebrities! Holograms! Avant-garde! Drama!

“Items: Is Fashion Modern?” which opens at the Museum of Modern Art on October 1, has none of these things, and that is the point. It does not focus on a specific brand or style (nor sell you its clothes in the gift shop). You will not be transported to another world; your heart will not soar, nor will you get chills. You will not get a good Instagram. You won’t even be confused, and then have to pretend you’re not. Instead, MoMA’s new exhibition puts your world on display, which is why you’re going to find it just as interesting.

This is MoMA’s first fashion-focused show since 1944, so clearly the museum is trying to keep up with the trend. But “Items: Is Fashion Modern?” is still a design show at its core. Rather than curating a fantasy wardrobe, the exhibit takes the quotidian contents of our own closets, from Calvin Klein underwear to Converse All Stars, and places them inside glass boxes or on white walls, illuminating, enchanting, and elevating their history, cultural significance, and artful design. What the exhibit lacks in stylish flair, it makes up for in pathos.

The exhibit’s curator, Paola Antonelli, started by asking herself the question: “What garments changed the world?” She spent years making a list of items, which grew to be about 400 long. Later, when Glenn Lowry, the museum’s director, suggested she turn her list into a show, Antonelli painstakingly chose an elegant 111 with the help of assistants, as well as a committee of scholars, editors, and designers including Penny Martin, Valerie Steele, and Shayne Oliver.

“The simplicity of these absolutely functional garments that, because of history, become invested with so much power, is a marvel,” Antonelli told a crowd Tuesday morning, when the exhibit opened to the press. “We want people to come into the exhibition recognizing that anything that they wear at any time can be a symbol; and a symbol that is world-changing.”

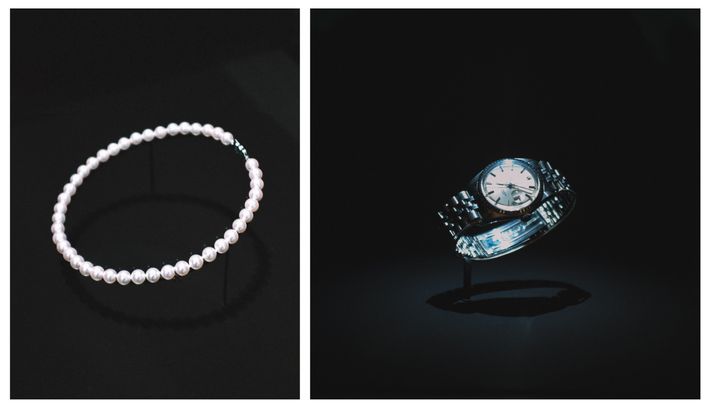

When I first entered the show, its expanse read as a startling quietness in contrast to its hype. The open-plan gallery covers the entire sixth floor of the MoMA, and with no visitors in it besides fashion editors, the some 350 objects on display (many “items” are expanded to include more than one example) felt disparate and almost lifeless — a common fate for pieces held captive in museums. A purple ’80s MTV fanny pack, for example, was muffled. A Rolex watch seemed small. A row of “little black dresses” resembled the Met’s “Death Becomes Her” show instead. By the time I hit the 70th item or so, I wanted to breeze through the rest.

But after visiting the exhibit a second time on Tuesday night, when it opened to museum members and the designers behind many of the items on display, my opinion changed. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a museum show so full of energy. Granted, the crowd was made up of people who literally pay money to be excited about MoMA shows before anyone else, but the objects on the wall brought out everyone’s most basic human impulse: to get a rise out of recognizing oneself. I ended up staying for two hours, eavesdropping on various reactions.

“My mom had that!” said one museumgoer of the MTV fanny pack. Another wore a contemporary version across his shoulders. Standing in front of a purple Patagonia fleece, a woman recounted a story about her husband wearing the same one on the back of a camel during their family vacation. Another person I spoke to was just happy to see a do-rag on the walls of a museum.

The sheer number of cultures, subcultures, and style tribes represented in the exhibit makes recognizing oneself an easier task than at most museums (or on other floors of the MoMA, for that matter). Levi’s 501s are given just as much real estate as a shimmering Armani suit. Burkinis are shown next to skimpy bikinis; saris next to Diane von Furstenberg wrap dresses; kippahs adjacent to hijabs. The exhibit is just as much a photo album (or a selfie, if you want to go there) as it is a textbook, and visitors are asked to do the work, too. In addition to learning something new about familiar objects, we’re also confronted with the totems of other cultures and classes, and how we’ve been hardwired to read them. Antonelli does not shy away from visual “stereotypes,” as she puts it, nor the politics behind even the most unsuspecting objects.

“The hoodie is one of the most important items in the exhibition, from all viewpoints, but especially politically,” said Antonelli of a red Champion hoodie that was given its own wall in the center of the show. “It’s extremely functional and protective, but we also like to say that it gives the false impression of being invisible,” she continued. “It’s a double-edged sword because, you know what happened: You think you’re invisible, but other people think you’re threatening.”

Antonelli was of course referring to the case of Trayvon Martin, a 17-year-old African-American teenager who was fatally shot in 2012 by George Zimmerman, a neighborhood-watch volunteer who reported him as “suspicious” for a wearing a hoodie. Other, more blatant, politically charged items in the show include a “Silence Equals Death” graphic T-shirt, balaclavas, lapel pins, and a red sports jersey bearing the name of the NFL player Colin Kaepernick, which Antonelli put it on the list over a year ago.

In addition to cataloguing items that have changed the world thus far (for better or worse), the exhibit also looks ahead by asking a handful of designers to update the “indispensable” pieces they’d like to see in the future. Kerby Jean-Raymond of the New York–based label Pyer Moss, for example, revisited Pierre Cardin’s Cosmos Collection. Though Cardin was interested in making clothes for outer space, Moss focused on how to survive global warming, specifically rising sea levels, with an inflatable wetsuit dress. Meanwhile, Lucy Jones designed tights for those with physical disabilities.

Despite all this, most visitors will leave the exhibit feeling like something is missing — a challenge that Antonelli also encourages. Where are the socks? Where are the glasses? What about a wedding dress? Why are there five pairs of Margiela shoes and no Crocs? (This was my question.) Antonelli’s answer is always the same: Post your 112th item on social media and hashtag it. She’ll take a look.

If you are able to brave the inevitable crowds at MoMA, “Items: Is Fashion Modern?” is worth a trip uptown. And probably more than once, if you’re really going to see it all. You will most likely leave feeling accomplished, as though you too just made an organized list. As a whole, the exhibit reads as a listicle for a senseless world; a catalogue of the things we carry. It helps us understand why we are the way we are and buy the things we buy; and then what those choices can mean. (“What does your white polo say about you?”) It prompts over-analyzing and self-aggrandizing, but is also detached, in the way museums tend to be, allowing you to insert yourself in new shoes, old, and foreign. It needs you as much as you need it.

The exhibit begins with underwear and ends with a plain white Hanes T-shirt. It is mounted on a wall and well-lit across from a row of suits — a comment on power and how our signifiers of it have changed in fashion over the years. (See Mark Zuckerberg.) The plain white T-shirt is unisex; it is basic; it is a symbol of consumption. It is also a blank canvas in the same way that Kazimir Malevich’s White on White, which also once hung in the museum, is a blank canvas.

“Look, baby! You have a whole drawer of these,” said one woman as she walked by the Hanes T-shirt with her male partner. He nodded, seemingly pleased with himself and the show. He swerved over to the lengthy description placard before heading out, but didn’t read it. I can almost guarantee you, though, that he thought about it the next morning when he put one on.