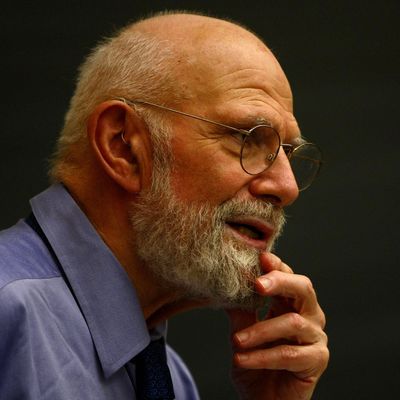

The late British neurologist Oliver Sacks once wrote that, more than a doctor or a traditional scientist, he considered himself someone who worked in“existential neurology.” It’s a fitting descriptor for someone who made a career of concerning himself less with the brain than with the mind — and it’s also a focus that’s especially apparent in Sacks’s new, posthumous collection of essays, A River of Consciousness, out later this month. True to form, Sacks continues in this latest collection to focus on questions over answers; the result is a work that leaves plenty of room for possibility beyond what might be immediately observed.

While this new collection does explore the functionality of the brain — how it perceives time, how it crafts memories, how it sifts through thoughts to foster creativity — Sacks appears to be even more interested in exploring the mind’s metaphysical and existential implications. If people perceive time in varying ways, for instance, what does that say about time itself? If we misremember the past, he wonders, what else might we be wrong about? If creativity is largely a subconscious phenomenon, what else might be happening to us without our knowing?

Sometimes, this philosophical exploration seems to work against him. Like many popular authors, Sacks was accused during his lifetime of diluting the scientific complexities of his findings — or finding none at all. As the British neuroscientist Ray Dolan told The Guardian in 2005: “Whether Dr.

Sacks has provided any scientific insights into the neurological conditions he has written about in his numerous books is open to question. I have always felt uncomfortable about this side of his work …”

But academic rigor never seemed to be Sacks’s foremost goal, nor was producing new findings. Instead, the clearest common factor that that binds this collection’s varied essays is what also bound together much of his professional life: an overarching desire to humanize the otherwise aberrant. In “Speed,” for instance, Sacks tells the stories of people with severe Tourette’s syndrome who have trouble interacting in daily social situations, but who are able to comprehend time at such a strikingly different rate than the rest of us that some “are able to catch flies on the wing.” When Sacks asks a man with Tourette’s how he understands time, Sacks writes that “he had no sense of moving especially fast but rather that, to him, the flies moved slowly.”

Sacks also addresses questions with remarkable broadness, like the question of what a mind really is. In “Sentience: The Mental Lives of Plants and Worms,” he posits that “minds” might not belong solely to humans and animals. “Plants ‘know’ what to do, and they ‘remember,’” he writes, while “the tiny, stalked, trumpet-shaped unicellular organism Stentor employs a repertoire of at least five different responses to being touched.” Is the ability to respond to stimuli, he wonders, a sign of a mind?

What is forever frustrating about Sacks is that while he clearly has a handle on the science behind the ideas he floats, he doesn’t always trust his readers to be interested in it. Some of the essays are entirely devoid of case studies or even the slightest scientific specifics (the collection’s title essay is the densely scientific exception). In “The Fallibility of Memory,” Sacks opens with a personal story about falsely remembering a childhood event, before moving on to an exploration of plagiarism and ending with a discussion on Freudian slips. Not once does he touch on the bevy of scientific research about memory, of which he no doubt had a strong understanding. Likewise, in “Mishearings,” a particularly short and funny essay, he stays almost exclusively in the realm of personal experience.

This lack of scientific specifics isn’t necessarily a negative, and the fact that most of the essays were originally published in outlets intended for wide audiences rather than academic ones probably made it a necessary choice. (Nine of the ten essays in The River of Consciousness originally appeared in The New Yorker, the New York Times’ opinion section, The New York Review of Books, or other essay collections.) But it is crucial to know that these are not scientific essays so much as essays about science —explorations of perhaps unknowable concepts as seen through personal, historical, and literary lenses. This disciplinary cross-pollination results in essays that have scientific sources taking a back seat to paragraphs of memoir, or to writers Sacks admired, like when he drops a page-long block quote from H.G. Wells.

More than anything, Sacks wanted to muck around in the wilderness of the mind that so few have yet to fully explore. In “The Creative Self,” the only essay of the bunch that hadn’t previously been published, he describes his own experience of “the creative spark,” noting: “When I am writing, thoughts seem to organize themselves in spontaneous succession and to clothe themselves instantly in appropriate words. I feel I can bypass or transcend much of my own personality, my neuroses. It is at once not me and the innermost part of me.”

He provides no explanation for why this might be so. But in a way, that makes for a refreshing read, a departure from the glut of books that claim to provide solutions to every facet of neuroscience. (Just Google something like “unlocking your creativity” to see the scores of books on the subject published every month.) Intellectually, Sacks is, at heart, a philosopher. But he is a philosopher looking not for answers but for increasingly grander questions. He asked a multitude of them throughout his 82 years, but “what is a mind?” might be his biggest.

If he were still alive, it wouldn’t be a stretch to expect that he’d one day find even bigger questions to explore. It is only the wisest among us who search not only for answers but also for questions. In his 1984 book A Leg to Stand On, he remembered a moment from childhood when his aunt wondered aloud how his life would pan out. “You’ve always been a rover,” he recalls her saying. “You seem to have one strange adventure after another. I wonder if you will ever find your destination.”