Oceans of digital ink flowed in the days after Hugh Marston Hefner, founder and editor of Playboy, died on September 27. There was no question about his creative legacy: The magazine he started in 1953 (and continued to edit nearly up to the end) was a triumph of lifestyle branding. Even if you don’t like it, you know what a Playboy man is, or wishes to be. But most of the discussion involved the fact that Hefner was, as we say these days, Problematic. Yes, he perhaps helped loosen the bonds of sexual repression and thus helped women; yes, his magazine crusaded for abortion rights. But above all, he also ran a highly visible and cheerful argument for the objectification of women. Playboy, after all, was not merely clueless about the concept of sexual harassment; it was built upon it. One of the first centerfold models was a member of the magazine’s subscription staff, and she had agreed to pose topless in exchange for getting Hefner to buy a new address-label machine.

He was also better at creating that lifestyle than he was at maintaining an empire. After 25 years of great dramatic growth, Playboy Enterprises was in deep trouble by 1982. The casinos that had provided 80 percent of its profits were closing, after gambling licenses in London and Atlantic City had been revoked. Other divisions, like book publishing, were losing money as well.

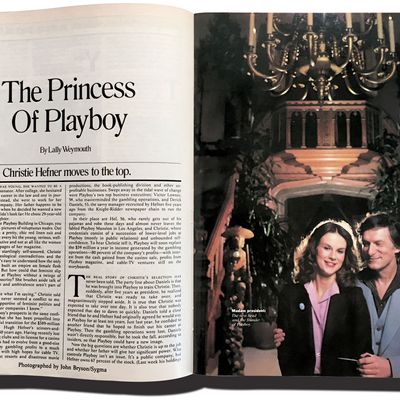

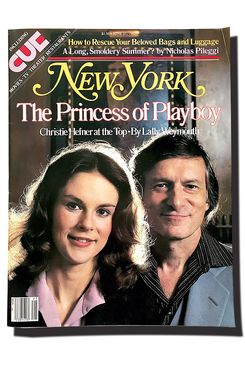

The solution was a new president, and the person who got the job was eyeopening in two ways: She was a woman, at a time when female top executives were extremely rare, and she was Hefner’s 29-year-old daughter, Christie. New York readers learned about her in “The Princess of Playboy,” Lally Weymouth’s cover story. (Weymouth perhaps understood the dynamics of the dynastic publishing business especially well, being the daughter of one Washington Post publisher, Katharine Graham, and the mother of a future one, Katharine Weymouth.) In the profile, Weymouth addresses mostly the business woes of Playboy and the tricky role of an inexperienced president who was nominally in charge of her controlling dad. “The big questions,” Weymouth wrote, “are whether Christie is up to the job and whether her father will give her significant power.” But there is also plenty about the Problematic. Gloria Steinem remarked to Weymouth that she’d been told stories about Christie’s teenage visits to her father’s house: “When Christie would turn up, the mansion was cleaned up, the kinky stuff put away, and the Parcheesi board taken out. There was this apparent effort to keep Christie from knowing what was going on.” From an editor at the magazine itself: “Christie should be running the Ladies’ Home Journal. She’s buying Hef’s line that Playboy is good for women. She’s become his little mouthpiece. How she lives with herself, I don’t know. You can’t be a rampant feminist and work for Playboy. It makes us look ridiculous.” And from an outside observer, a judge of the Hugh M. Hefner First Amendment Awards: Christie “has this giant problem — the apparent conflict between her genuine social interest and the enterprise she runs.”

Christie Hefner herself, of course, had plenty to say about all of this. (She had done public relations for the magazine in an earlier position.) “Playboy has been more supportive of feminist politics and philosophies than most other companies I know of — in its attitude toward hiring and promotion of women, through its editorial and financial support of the Equal Rights Amendment and abortion,” Christie told Weymouth. “I’m not the only feminist at Playboy. [Feminists are here] because the magazine is a fundamentally liberal and humanistic magazine … I don’t know what it means to be a feminist if you don’t want women in positions of power.” And that, indeed, she was.

It worked, too. Playboy, the company, stabilized and largely recovered under her guidance. She built the video and television arm — successful for a long time thereafter — and expanded the licensing business. Her father (who, around the office, is said to have referred to his daughter as “corporate,” as in “Ask corporate about that”) did give her some power, and his colleagues routinely credited her with saving the business. She stepped down in 2009, as the bottom began to fall out of both the DVD and magazine businesses, especially in the adult industry. The Playboy brand — largely a licensing operation, built atop a magazine a tenth its former size — is now overseen by Christie’s half-brother Cooper. He’s 26.

*This article appears in the October 2, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.