I Think About This a Lot is a series dedicated to private memes: images, videos, and other random trivia we are doomed to play forever on loop in our minds.

From 2011 to 2015 and occasionally after, I worked for Rookie, an online magazine and book series for teenage girls. Rookie has a fairly straightforward mission: to speak honestly with teenagers and give them rad things to look at and think about. Near the end of my time there, I discovered Chop Suey, a 1995 point-and-click computer game created by the writer and multimedia artist Theresa Duncan. When I played it, I felt as though, 20 years before Rookie existed, Duncan had scrawled its predecessor onto a CD-ROM. Chop Suey was officially marketed to ages “8 to 15 to adult,” but as Theresa Duncan told an interviewer in 1998, “My stated goal in life is to make the most beautiful thing a 7-year-old has ever seen.”

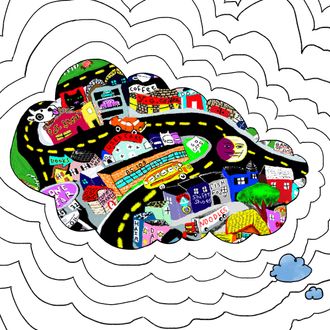

Duncan decided that the most beautiful thing a young person could see was something possibly similar to her own life. In Chop Suey, the sisters Lily and June Bugg do nothing more than wander around their town with a takeout hangover, observing their neighbors. It’s more of a set of vignettes than an adventure, or a linear cartoon picture book. You can’t win or lose. What you can do is visit a candy store called Cupid’s Treats, an observatory, the home of ribald Aunt Vera and two of her three ex-husbands (all named Bob), and other screwball locales.

Duncan was an aesthete, and it’s maybe demographically off-key to call this a sensual game, but it is. Chop Suey places Lily and June Bugg’s world in the context of the wider one, synthesizing dreamt-together towns and cities and the work of real, live artists. Chop Suey was illustrated by Monica Gesue with help from the musician, author, and artist Ian Svenonius. Highly stylized, each scene looks like a patchwork quilt rendered in Magic Marker. The game is all about empiricism: The point is to touch everything you can and see what animations, dialogue, and music your prodding shakes loose.

A lot of what you investigate in the game is contingent on the game’s hella lush audio. Chop Suey was narrated by the not-yet-famous author David Sedaris, voice-acting the role of the moon who also serves as the cursor. (At the time, Sedaris otherwise worked as a part-time house cleaner.) The game’s score was composed and performed by members of the political punk band Fugazi and the wider Dischord Records scene. Here, their music examines the merits of pickles.

The game never reveals Lily and June Bugg themselves, save for their brown and white legs as they “dozed amid the flowers and the grasses on a low green hill” in the game’s introductory frames. As that wording suggests, Duncan isn’t embarrassed to be ardent in her language, and her observations exemplify her empiricist knack. In that first scene, the sisters “didn’t know the names of the flowers in which they lay,” so June Bugg extracts a Queen Anne’s lace blossom and names it herself: rose. The flower is “decidedly un-rose-like,” but who cares? The character doesn’t need to be lectured about what she should interpret of her interactions with the world — that girl is right just as she is. (Given how thoughtful and precise Duncan was in her diction, I’m all the more irritated and disappointed by her decision to take an appropriative, “Asian-sounding” phrase as her title — we don’t know if Lily and June Bugg are white, but Duncan was.)

I probably would have loved Chop Suey in the ’90s, but I didn’t know it existed then. I found out about it in the contemporary way that most people do: reading “The Golden Suicides,” a sordid story about the 2007 suicides of Duncan and her husband, the artist Jeremy Blake. In it, Nancy Jo Sales writes mawkishly about the couple’s “meltdown” — in the last years of their lives, Duncan and Blake became paranoid that they were being harassed by Scientologists after Blake designed the cover for Beck’s Sea Change. In setting up who she thought Duncan was, Sales spends plenty of time characterizing Duncan as “lovely,” “gorgeous,” and “sexy” before her games come up — when they do, glancingly, in the third section of the piece, it’s only after Duncan is called “the pretty girl” of video games. Gendered fawning was common in the press around Duncan at the time of the games’ releases — and, even dead, Duncan’s allure overrode her work. Duncan once satirized what it was to be an artist turned femme phenomenon in an animated short, The History of Glamour, which appeared in the Whitney Biennial in 2000. She knew that even while trying to espouse freedom from gendered ideals within girl-media, people outside of it are quick to appoint you an “It” girl — the awful designation that makes twins out of “female” and “object.”

Unlike its peers in the “girls’ game movement,” Chop Suey isn’t given much attention as a notable entry in that genre. This might be because, also unlike its peers, it doesn’t simperingly demonstrate how to perform the duties of a homemaker, a fashion plate, or even a socially obsessed teenager. Chop Suey simply looks out at a town. This reminds me of an essay by the cultural critic Roland Barthes. He wrote about how toys are little more than adulthood training devices — how many children’s playthings are designed only to mimic their future responsibilities. Barthes says, “There exist … dolls which urinate; they have an oesophagus, one gives them a bottle, they wet their nappies … This is meant to prepare the little girl for the causality of house-keeping, to ‘condition’ her to her future role as mother.” Basically: What you give to children as entertainment tells them whom to become.

CD-ROMs were a new kind of toy in the mid-1990s and given her writing, artwork, and interactions with the media, it’s clear that Duncan understood so personally what others thought a girl’s role in a game, as in reality, was supposed to be. She was affronted by that but, even more so, hopeful that she could expand it. She used Chop Suey to evince a truer story about what might matter to girls. Her example, in doing so, will always matter to me.

As this seminal Motherboard article about Chop Suey mentions, there’s a part of Sales’s Theresa-and-Jeremy story about a party Duncan hosted near the end of her life at the couple’s apartment, in the St. Mark’s Church rectory. According to a guest, “Duncan dragged out of a closet her old CD-ROMs and a copy of The History of Glamour. ‘Everybody kind of looked at each other like, Oh no, what is she doing?’” That breaks my heart in half. Duncan wanted people to remember her work, and so I think about Chop Suey a lot because I want to do that for her.

I want to remember the human oddities she portrayed to girls as worthy of attention: Aunt Vera waltzing around a picnic table with her gas-station-attendant boyfriend; the “noises that made each night a poem;” the “fish samawiches” offered at the local takeout spot. In their specificity, all are more familiar than most aspirational gloss thrust on girls’ media products. Maybe a player’s neighborhood, or the people they knew, were something like this ritzy, rinky-dink town — and so their lives were noteworthy, too. The most beautiful thing I could have seen as a 7-year-old would have been that my observations were interesting all on their own, without the expectation that I needed feminized refinement.

The meandering-around and kind visions of the world that glow in Chop Suey are the most captivating part of Duncan’s life, regardless of the preoccupation with how she died. For me, that’s too conclusive. It doesn’t pay enough attention to the details. Getting to the ending was never Theresa Duncan’s point.