Email your money conundrums, from the technical to the psychological, to mytwocents@nymag.com

I’ve been in some awful work ruts — the kind where my brain feels constipated, I can’t see a path forward, and I’m fighting back tears at my desk for no reason besides a sense of general failure. And I’ve had (mostly) decent jobs! Which is one of the worst things about feeling stuck and burned out in your career, as 77 percent of us have: Often, you can’t even put your finger on what’s wrong, what would make it better, or how to dig yourself out of that stressful hole you’re wallowing in. You could try drinking more, or seeing a therapist. Or you could read.

The term bibliotherapy was first coined in 1916 by Samuel Crothers, a Unitarian minister who believed in prescribing books to help people deal with their troubles. More recently, bibliotherapy has been incorporated into medical treatment programs for depression and other psychological disorders, with positive results. Meanwhile, researchers have found that reading fiction improves general brain function and connectivity, boosting emotional intelligence and even muscle memory — handy skills for any job. The right book at the right time, be it a novel, an autobiography, or self-help literature, can be a real kick in the pants, workwise and elsewhere. Here are eight suggestions for your office ailments.

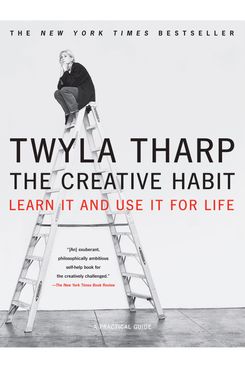

When you’re out of ideas:

This memoir-slash-life instruction manual is intimidating at first. One of the world’s most celebrated dance choreographers, Tharp is intensely disciplined and adheres to near-militaristic rituals: She rises before dawn every day to work out with her trainer, eats three hard-boiled egg whites for breakfast, and files reference materials for her projects (index cards, music albums, photographs) in meticulously organized cardboard boxes. Extreme? Sure, but it’s also a hyperspecific portrait of the granular, painstaking, day-to-day effort it takes to succeed at grand creative endeavors. Tharp also breaks down her own processes into small, simple exercises that anyone can do (questionnaires, memory prompts) and extols the benefits of what she calls “scratching” — groping around at little concepts until they cohere into something useful. You don’t need artistic aspirations to get a lot out of this book; it’s more of a general road map to developing bigger, better ideas, and staying focused on them.

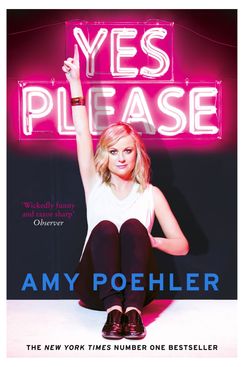

When you’re feeling unappreciated:

Obviously, this book is funny, and therefore good for anyone in the dumps. I read it when I was trying to decide whether I should quit a miserable job that looked impressive on paper for a much less glamorous job that seemed fresh and different, and this passage pushed me over the edge: “Treat your career like a bad boyfriend,” Poehler writes. “Your career will openly flirt with other people while you are around. It will forget you birthday and wreck your car. Your career will blow you off if you call it too much. It’s never going to leave its wife. Your career is fucking other people and everyone knows but you … If your career is a bad boyfriend, it is healthy to remember you can always leave and go sleep with somebody else.” Poehler’s advice isn’t to take yourself (or your career) less seriously — it’s a reminder to not let your pride get in the way of your options, and that you are never truly trapped.

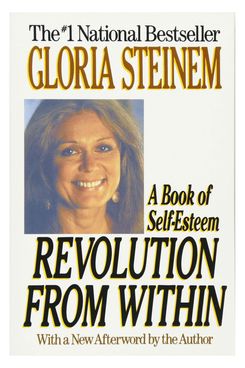

When you’re apologizing nonstop and can’t seem to do anything right:

A best seller and cultural sensation when it was originally published more than 25 years ago, this book is a bit dated now (even the word self-esteem feels very ‘90s), but the message still resonates: A strong core of self-respect produces more fulfilled, productive people, and there’s a lot of data to prove it (the book is heavily footnoted). “Self esteem isn’t everything,” Steinem writes, “it’s just that there’s nothing without it.” She is not peddling blind, everyone-gets-a-trophy confidence; instead, the book is about fostering your own independence and individualism, pushing your own boundaries, and then squaring them with the obligations and pressures of our society (which, of course, has changed since the H.W. Bush era —but not by that much). Do some of the book’s exercises veer into finger-painting, drum-circle cheesiness? Yes. But they’re also fun and approachable (orgasms: recommended), and you’ve got to start somewhere.

When you’re afraid you’re not creative enough:

Oprah Winfrey gave copies of this book to Stanford University’s entire graduating class when she was the school’s commencement speaker in 2008. This book also prompted a friend of mine to quit her lucrative job in sales and go to grad school for nursing. Now she has a Ph.D. and a high-level job at a cutting-edge health-care start-up. “It made me understand that my ‘right-brain’ skills are valuable in business, not just patient care,” she told me. “It also made me bold enough to argue that.” You may recognize Pink from his TED Talk, “The puzzle of motivation”; he’s also written six books about human behavior, but A Whole New Mind remains his longest-standing best seller. It’s a quick, upbeat read that defines six different abilities (including empathy, play, and story— all distinctly “creative”) that are becoming more economically and socially valuable in the digital age, as “left-brain” tasks becomes increasingly automated. Pink also provides useful tools, exercises, and further reading to cultivate these skills, should you worry yours are lacking.

When you just can’t focus:

I devoured this short book on a two-hour plane ride, and it made a big impact on my work habits. (Namely, I started paying attention to when and where I worked best —in the early morning, at home —and structuring my days around it. I also set up a website blocker to save myself from mindlessly browsing, say, new bathrobes and J.Crew sales during those hours.) Written by a psychiatrist who specializes in attention-deficit disorders, Driven to Distraction is for people like me who don’t need medication but do struggle with garden-variety attention deficit traits (or ADTs), whose symptoms include nail biting, compulsive phone-checking, and flitting from tab to tab with a million half-written emails. Sound familiar? Hallowell outlines six common ADTs, complete with tables that list their positive and negative aspects (who doesn’t love self-diagnosing?), and provides constructive plans for overcoming them. Put your phone in the other room while reading.

When you need to do some soul searching:

This book has a permanent home on my bedside table, as I find it equally comforting to read when I can’t get up in the morning or when my mind is racing at night. On its face, of course, it’s about how to write memoir, based on Karr’s own work (she’s written three) and the curriculum of her hyperselective graduate seminars. But Karr’s wisdom is useful for nonwriters, too, because it addresses thorny issues that most careers entail — how to earn strangers’ trust, self-edit, battle periods of doubt, manage the disappointment of not living up to your (or your colleagues’ or family’s) expectations, and hone your point of view. At best, it could inspire you to write something, but at the very least, it’ll help you understand the power of human ego and how to spot its distortions, which is the crux of navigating any workplace.

When you’re having an existential crisis:

“Sheila cannot finish her play” is the title of one of this semiautobiographical novel’s chapters, and ultimately the spine of this whole book, in which the narrator flails around Toronto trying to complete a script she’s been commissioned to write. What I love about this story (and what some critics didn’t) is that Heti is so shameless about her obsessive, neurotic desire for meaning and guidance, even when she seeks it through unlikely means (divorce, blow jobs, coke binges, liquor, a job at a hair salon, a masochistic boyfriend). She’s also unapologetic about describing what most people would consider embarrassing flops, choosing to observe and obsess over them (as we all do) instead of neatly packaging them as “learning experiences.” Make no mistake: There is nothing prescriptive or self-help-y about this book, but that’s part of what makes it great, especially when your own career is feeling aimless and messy.

When you know failure is supposed to be “good,” but really?

Sarah Lewis is a professor of art history and African-American studies at Harvard, as well as the woman behind the popular TED Talk “Embrace the near win.” Her deeply researched book is a continuation of that “near-win” philosophy: how striving is actually a constant state, the world’s top achievers have a litany of “failures” in their wake, and “success” is overrated (if it even really exists). She argues that we should take a more playful, experimental approach to our work, rather than viewing goals in stark, right-or-wrong terms. In addition to referencing hundreds of “near wins” from history (Samuel Morse was a failed painter before he invented the telegraph, Kafka never finished most of his books), she incorporates interviews with a wide swath of scientists, athletes, executives, and academics. If you’re looking for a more cerebral examination of human effort and its discontents, then this book is for you.