Self/Reflection is a week of stories on the Cut about how we feel, versus how we look.

I once assigned my undergraduate poetry students to prepare a poem of any kind on any subject, asking only that it be written on something other than paper. On the day the assignment was due, we squinted at an epic poem inscribed on the inside surface of a pack of American Spirits. We went on walkabout to see the short love poem carved into the base of a tree. A student had his frat brothers carry in a small boulder he had penned his piece on. One young woman stood up at the end of class, turned to face the window, and removed her shirt. She was the friend of a student in my class, who had painted her poem on the friend’s back, and there she stood, naked, to reveal what the poet recited. The poem was about being young, and beautiful, and afraid of getting older. “I love it,” the friend said. “I hope it never washes off.”

“Love is a thing that can never go wrong, and I am Marie of Romania,” wrote Dorothy Parker, she of the elbow star tattoo. There’s a mistaken thinking around tattoos — particularly directed toward women who have them — that they come from a fear of things changing, some unhealthy desire to keep things as they are. “Why would you do that to your body?” “That’s not going to look good at 70.” These are the things strange men say to tattooed women on the street, on a bus, in a restaurant, at the doctor’s office. I got my first tattoo — a lyric on my arm from the great British poet Robert Plant — for no better reason than exactly what those men on the street assume about women like me. That I wanted to mark my beauty, my youth, because I was confused about death and permanence, because I could not imagine getting uglier or older or sadder or wiser.

It took me a long time to learn what exactly the difference was between painting a poem on your body or drawing a sun on your knee in Sharpie at camp and actually getting your flesh injected with ink — except the obvious difference that one was infinitely cooler. When you’re young, it’s hard to feel as if you’re doing anything more than seeking passage within your body, and we find all kinds of ways of taking control, of trying to make the body stay. It took me a long time to learn that good tattooing, like all good art, is less about a yearning for permanence than about the desire to capture change. Not to arrest, but to see in the way of remembrance: Change is real.

I think of a good friend, a master artist who’s been tattooing for 20 years. He tells me that 15 years ago he started tattooing a lot of cover-ups for women who had been cutters in their teen years. And now, he tells me, it’s all the time. It’s mostly flowers. He says they want to plant a garden in the tracks. He had a woman once come to him who had been so severely beaten by her husband he’d ruptured her femoral artery, and her thigh and leg were obscured in the matrix of veins showing through. She’d always been fascinated by tattoos, but that husband hated them on women and hated women who had them, so now, divorced and in her 50s, she covered up his abuse with a dragon wrapped around her thigh down to her ankle.

It’s always intimate for me, says my tattoo artist friend — man or woman. But while he’s working, he won’t talk unless you want to. And he doesn’t want to generalize, but many women want to talk. There is a point at which intimacy becomes abstraction, when the camera gets too close to the flesh, rendering it animal, when the wings get too close to the sun, rendering it death itself. But when women talk to me, my friend says, I feel our closeness actually dampens the risk of dissociation. I want to bring magic to it, he says, and that magic lives in conversation. Their stories are about taking ownership over their bodies and over past pain and over fear and over the mutilation that they’d brought to themselves, this time a change by choice. Think of the women who get beautiful tattoos where their nipples were after double mastectomies. Or trans folk who choose to accentuate scars that themselves mark deliberate, wrenching change. Putting things down is the art of leaving them behind — but that is not as blunt as forgetting.

On my arm, there’s a masterful rendering of Rockwell Kent’s iconic portrait of Moby Dick breaching. Rays of sun beat on the whale, streams of water fall from his body. Another is a small blue wave I’d seen a friend doodle in her notebook in college, and we were having a good day, so I got it tattooed. I have a flower on my back, another on my arm, and a swan on my thigh, the cover art off my 22-year-old self’s favorite record. More, still. Though the catalysts for these decisions have largely been lost to time, the tattoos are not among the things in my life that I regret. This kind of art fades, like love — in importance, in relevance, in vibrancy. It’s a sign that whatever you’re marking, good or bad, will lose its power and be diminished. A reminder that you are not what happens to you, but how you choose, again and again, to react. So the changes of love and joy, as much as pain, are marked in tattoos — and when I mark a good thing, even great love, by the work of another person’s hand on a body that will change, I am accepting that the thing I grab close is going to be altered, too.

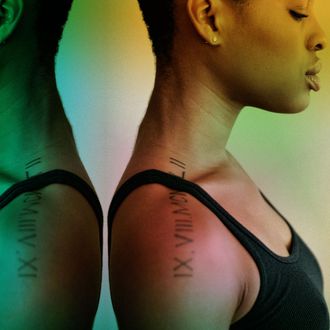

My most recent tattoo is one view of a gastropod shell, on the back of my upper arm where I never see it. My husband got another view, in the same spot on the opposite arm. It would be — and still is — the little home we carry with us. It was a gift to ourselves we couldn’t afford in the week after our wedding. When we lay there together, in pain and exhilaration in a strange studio in Miami, we laughed with the artists about the irony — that kind that’s more like truth — of what we were doing. Had done. Marriage is not an attempt at staying the present. At least, good marriages aren’t. And neither are good tattoos.