In 2010, journalist Abby Ellin, then 42, became engaged to the man with whom she believed she would spend the rest of her life: a handsome and charming 58-year-old military doctor who worked at the Pentagon and was supposedly involved in top-secret missions and counterterrorism operations. She had first interviewed him for an article for which she had needed a medical expert’s opinion a few years prior, and the two had stayed in touch.

The Commander, as she calls him, popped the question five months after their first official date. But their relationship deteriorated — they weren’t spending enough time together, she began to mistrust him — and by early 2011, they split. The following year, he was arrested for writing fraudulent prescriptions for painkillers, and from there, other details about his life began to unravel. Ellin, who has written about weddings for the New York Times’ Vows column for years, learned that most of their relationship had been a complete lie: He wasn’t a Navy SEAL or working undercover with the CIA, and he had been engaged to another woman at the same time as he was with Ellin.

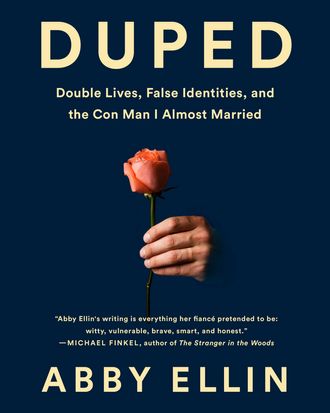

As Ellin processed her own betrayal, she was inspired to find other people who were deceived in similar ways and understand why it happens. Her new book, Duped, examines various stories of double lives and the victims they leave in their wake. The most striking examples are often the most banal, highlighting how the most duplicitous of liars can carry on otherwise ordinary, even boring, lives.

There’s been a widespread cultural fascination with scammers lately, and here Ellin talks to the Cut about why we have such a voracious appetite for those stories, the fallout from her relationship with the Commander, women’s relationship to deception, and more.

How did people react after the Commander was exposed? Had anyone suspected him?

A friend of mine was like, “I knew it!” And my mother was sort of like, “Yeah you got mad at me when I told you that I didn’t believe it.” But when everybody first met this guy, they loved him as well. He was so nice to everybody. He was so charming, so I think everybody was surprised.

In the book it seemed like you had some reservations along the way — looking back, what exactly held you back from investigating further?

Yes, I’ll tell you exactly, and maybe you can relate. We’re journalists. We’re trained to question everything, and I found it very hard to curb my natural curiosity and interrogation. I’ve been told that I should’ve been a trial lawyer sometimes, which is not the most attractive thing. I was really trying to figure out how to be in a relationship without being this, y’know, total journalist.

You ended up striking up a friendship with the Commander’s ex-wife, could you talk about how that’s helped you process your own betrayal?Gee, not only did I became friends with her, I became friends with the woman he was with before me — I mean, concurrently with me. So I became friends with her and then I became friends with the woman he was with immediately after me, who he was courting her as well when he was with me, and she is the one who ultimately helped nail him with the cops. She has since died, but she was lovely. They’re really smart women, and I thought, okay, so I don’t feel like such an asshole.

Do you know what he’s up to now?

Well, last I knew he filed for bankruptcy. Although recently I got another LinkedIn request from him, and I think it was just one of those mass “Be my friend on LinkedIn” and I didn’t respond. From what I know, he’s still working on some humanitarian organization. I haven’t talked to him in eight years.

My editor gave me this book because she knows I’m fascinated with stories about secret second families. To me, it’s such a particularly interesting form of deception because you’re not really benefiting from it — you just have double the responsibilities now. Did you come across any other sorts of stories where the deception didn’t necessarily benefit the person who was lying, and just became another obligation of sorts? Well, the big one that surprises everybody was Charles Lindbergh. Four families. What is the point of doing that? There was another deception, this wasn’t a secret family, a woman in my book who was living with a woman platonically, a roommate, who told her she had cancer for five years.

That one was so disturbing — the most viscerally disturbing one to me, actually.

For me too, because that was totally unnecessary. What are you gaining from it? Other than having this person take care of you and these people worry about you, and maybe that was the goal. But I found that one so unsettling. It’s a good question, why would people want two families, double the responsibility? I think it involves the split of “I want the city mouse and the country mouse and all of that,” but what about when they’re living around the corner from each other? I think it’s living on the edge and living with the threat of discovery looming around every corner and I think there’s something really intoxicating about that and I think also having a secret that no one else knows. I think that’s really enticing for certain people.

You’d also think it’d be more difficult to pull something like that off, what will the prevalence of social media. Can you speak to the role of the internet in terms of either aiding or curbing these deceptions?

I think the internet totally makes it possible. Yes, it is easier to get caught. But, look, you can call up somebody and they can give you a fake glowing review from your last employer. You get an app that will make sounds of a train taking off, right, when in fact you’re at the hotel with your lover. You can get fake doctor’s notes, fake hotel bills, fake receipts for fake office furniture. So I think, and then anybody can find anything out, they just really have to be willing and trying, wanting to do that. I said to somebody, “Why are you lying, why are you telling your wife you’re going to a college reunion when in fact you’re at the Hilton Garden and she can check that you’re not there?” And he said, “Not everybody is doing what you would do.” “Not everybody is a suspicious bitch,” I suppose was the takeaway.

Why do you think women are deceived in relationships more often?

I think that we want to believe in love. I think everybody wants to believe in love, but I think there’s a little more wrapped up for women. I’ve written the Vows in the New York Times for years, and I can’t tell you how many people want to be in those pages. I get contacted so much by people who want to tell their stories, partially because it’s a good story that they have, but partially because it’s a sign of success: “I’ve accomplished something, I got married.” I think for women, no matter what we’re doing, there’s still something wrong with you if you haven’t been married or not married. It’s changing, but I still think it’s there and it’s different for men. A single man is a commodity and a single woman is considered a hindrance. I think women — with all of that, and the natural desire to be with a partner — I think that we’re more willing to suspend our disbelief.

You also wrote a chapter about women committing deception. Was there anything particularly surprising that you learned while you were working on it?

What really made me very happy was that, it’s not that women are so much better [at being honest], it’s just that we haven’t had the opportunity and that’s sort of didn’t really occur to me. One thing I thought was really interesting is that a study found that parents act more dishonestly around their sons than their daughters. They don’t want to teach girls that lying is okay, but they don’t feel so bad teaching boys that.

There’s real pop-culture appetite and appreciation for scammers — take, for instance, the story we did on an Anna Delvey, the fake German heiress. People talk about her like a real folk hero.

Well, you look at Frank Abagnale, Catch Me If You Can. Clark Rockefeller, Jayson Blair, Stephen Glass. We’re fascinated by imposters and I think part of it is because we want to know how they did it and part of it is also we want to learn how they did it so we can protect ourselves. And part of it is we envy them in a weird way, or we’re admiring of them. Look at Waldo Demara, the Great Imposter, and he passed himself off as a surgeon and a professor and a social worker and that — he wasn’t any of those things, but he just happened to be good at them. He was a damn good surgeon and we’re admiring of that. These are people who cut corners. We’re very admiring of people who succeed by cutting corners. We hate them, and yet we’re captivated by them.

Were there any stories that you couldn’t include in the book that you want to tell me about?

There was a story of a woman I know who had a company here in New York and she became very good friends with the office manager. She hired the office manager and the office manager was stealing left and right. The office manager had aliases and she ended up getting caught and prosecuted. But my friend — she saw it as this huge, huge betrayal — and she said, “But you know, it was my fault, I didn’t check the recommendations. We didn’t think we had to.”

And that was exactly the point, if you don’t check up then we really don’t have anyone to blame but ourselves. Which brings us full circle: When you’re in a relationship with somebody, you’re not supposed to be checking up on them. You’re not supposed to be questioning everything they do.

Speaking from your personal experience, what do you think is an appropriate amount of checking up? What do you think that people should be doing to protect themselves?

I think that I should be able to check everything you do and you should not be able to check what I do [laughs] is what I think. Every case is different. I know a woman who put a tracker on her boyfriends, some kind of software where the emails that were supposed to go to him, she was also getting copies of them.

Oh God, no.

I thought, you know, that’s just not good for many reasons, among them is that, how are you going to accomplish anything with your day? All you’re going to do is read these emails. I think you really have to figure out how how mistrusting you are. But I also think that, you know, if something doesn’t seem right, it’s probably not.

In the advice vein, did you come across traits common among serial liars or serial deceivers that can help people spot them?

They’re really, really smart. They’re really creative. They know how to tell stories. They’re raconteurs and they’re basically using their superpowers for evil rather than good. People who believe in their own lies are better because they’re not giving away any tells. There’s absolutely nothing that’s giving them away, so they could pass the polygraph because they believe in it. But somebody who seems too good to be true is probably too good to be true.

When you tell people about your story now, how do you think most people react? Is there empathy?

I’m getting, “What the fuck is the matter with you?”

Still?

I mean, it’s the first thing that they know. So I really wanted to make an effort to understand people’s psyches and what’s going on. And I think the bottom line is: Everybody wants to be loved. Everybody wants to be in love and we’re willing to do a lot of things to achieve that goal.