Fiber may not have the most glamorous profile — in recent decades it’s traditionally been associated with bowel regularity and Metamucil commercials. But what if it were, in fact, and in its own way, an embodiment of glamour? What if, in the end, few nutrients/food components hold a candle to fiber’s exciting and attractive appeal??

In Cultured: How Ancient Foods Can Feed Our Microbiome, science writer Katherine Harmon Courage makes the case that seemingly humble dietary fiber is not just essential for human health but also surprisingly weird and emotionally compelling. (Eating fiber is like feeding our own internal worlds, she writes, for instance.) She urges people “to try new things and learn to love dirty, rough foods.” Well, okay.

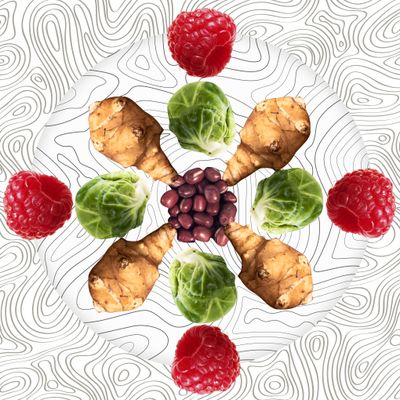

For a quick refresher, fiber is a type of carbohydrate that can’t be digested. It helps the body regulate blood sugar, and it turns off hunger. Beans and lentils are famously high in fiber, but so, too, are whole fruits and vegetables, like raspberries, apples, broccoli, brussels sprouts, and green peas. Whole grains like steel-cut oats, quinoa, and barley are also high in fiber (and here’s a longer list of fiber-rich foods). The daily recommended amount, for adults, is 20 or 30 grams.

In February, a report in the medical journal The Lancet found that people who ate the most fiber “reduced their risk of dying from cardiac disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and/or colon cancer by 16% to 24%, compared to people who ate very little fiber,” per the Harvard Health Blog. Today the average American eats only about half the daily recommended amount of fiber — and, according to Courage, only about 15 percent of the fiber that ancient humans used to eat (as determined through fossilized excrement). Has it really been fiber all along?

How does somebody know if they’re eating enough fiber?

Well, that’s a good question. I mean, I would say pooping regularly is a good sign!

Right? So that’s like, once a day? I don’t know?

Yeah. Roughly. I think everybody has their own normal, but yeah — just not feeling constipated and terrible is probably a good sign that you might be getting enough fiber.

I was reading a story about fiber that said the amount of money spent every year in the United States on constipation-related health care is in the billions — people spend more than $1 billion yearly on laxatives, for instance, and constipation-related hospital visits have apparently doubled from 1997 to 2007.

Wow. That does seem like a lot, but … I mean we really don’t eat that much fiber. There was a researcher, Dennis Burkett, who was doing health and nutrition work in the 1970s, a lot of which was done on the African continent. A researcher quoted him in a conference I went to, saying something to the effect of, “In countries where you have small poops, you need big hospitals.” And he was a big fiber proponent. [The actual quote is: “Big stools, small hospitals. Small stools, big hospitals.”]

I love that.

I thought that was interesting. Some of his research has since been, well, for lack of a better word, pooh-poohed, but I thought it was an interesting perspective. You don’t think about that aspect of intestinal health that often.

How much fiber do you eat? What does your diet look like?

I try to just be conscientious about it. Most meals and snacks, if I’m eating a salad or something, I’ll think, Let me add some beans or some other kind of legume to this, to add fiber. So I don’t think I go too-too crazy — I don’t totally shape my whole diet around fiber, necessarily — but I just try to always make sure I’m getting some at every meal. Steel-cut oats in the morning, for instance.

One of the things that I loved reporting in my book was that one of the prebiotics that we’re just starting to learn about is cocoa. [Prebiotics are high-fiber foods that feed the living microbes in our gut microbiome.] So like, unsweetened cocoa powder has some good fiber in it for your microbes, which is really great news, I think. I’ll sometimes have unsweetened hot cocoa in the morning, with my breakfast most mornings. Stuff like that.

Oh, that sounds good.

In the book, you mention the difference between microbes that are essentially full-time occupants in the human gut, and microbes that are essentially just passing through. I was wondering if you could explain that a little more.

Yeah! Definitely. I think this often gets overlooked when we’re talking about probiotics or fermented foods — like yogurt, kombucha, and kefir — because generally speaking, the microbes in our foods don’t hang around in our guts. They’ll survive the trip, and they’ll be beneficial to us while they’re in there, but they don’t repopulate our gut like we like to think maybe they do, like if we eat a yogurt or something.

Whereas the microbes that actually LIVE in our guts, for generations — those have really evolved to be there. Our gut is their preferred environment, and a lot of them can’t really live outside of it. So while microbes in general are all really diverse, there are, essentially, these two categories of microbes: the permanent and the passing-through. That’s a pretty human-centric way of looking at it, but I think it’s important to remember that while it’s great and awesome to eat all these fermented probiotic foods [like yogurt and kombucha], really taking care of the microbes that actually live in our guts and have evolved with us is maybe almost more important — or at least as important. And the best way to do that is to eat lots of fiber.

Is there a handy way to remember the difference between soluble and insoluble fiber? Or does it not matter?

I don’t think it’s all that important to know the difference. What I found in working on my book is just the importance of eating a diversity of foods. And making sure you get lots of different kinds of fibers. Because those will feed different kinds of microbes that live in our guts, and you’ll get different kinds of benefits. So instead of trying to learn all you can about every different fiber subtype, just try to eat a wide variety of foods that have fiber in them.

I tend to eat the same meal every day, which is probably a mistake.

I actually have been doing that lately, too. [laughs]

It can be so hard to come up with new stuff!

Exactly.

So, what are the health benefits of eating fiber? That sounds silly, but at the same time I really liked the way that you described it, and I was surprised.

Researchers are still learning and coming to understand these dynamics better, but it’s especially interesting, I think, because a lot of correlations that we’ve seen over the years between fiber intake and health outcome — it turns out that they might actually be modulated by the microbes in our guts. For instance, researchers didn’t always understand how polyphenols worked. [Polyphenols are plant-based micronutrients that can help reduce the risk of disease]. And they were like, “Well, we’re not breaking these down, so what’s happening? How are we getting the benefits?” But it turns out maybe our microbes are actually doing that work, and then producing compounds that help us.

So, basically, any benefit that your microbiome provides for you can be improved by eating more fiber, if that makes sense. Because fiber feeds our beneficial microbes, which help keep us healthy. And our beneficial microbes do things like improve our immune system and help us absorb minerals better, because they make our gut more acidic. [A fiber-fed] microbiome can also help us decrease inflammation.

In the gut specifically? Or elsewhere?

In the gut, but also in the body, which is probably tied into the immune system. The microbes keep it all in check, so it’s not being overactive. And fiber intake could also help protect against certain kinds of cancers, like colon cancer, breast cancer, and maybe heart disease.

There are no downsides, I would say, to eating fiber. Unless you really, really overdo it, and that might give you some … troubles.

Right. Well, so — supplemental fiber in pill form. Is that skippable, then? Or what are your thoughts on that?

I would say from my reporting that it seems generally better to focus on your diet, and make sure you’re getting all those fibers and nutrients from the whole foods that you’re eating rather than having a distilled thing in pill or supplement form. I don’t think it’s bad to take them, but I don’t think they’re as healthy as getting fiber from your foods. And because there are usually not that many different kinds of fiber in supplements, that means the supplements will only feed certain microbes in the microbiome. But if you have lots of different kinds of fibers, then lots of different microbes will be happy, and it will be better for you.

You mentioned cocoa, but are there any other under-appreciated, fiber-dense foods that people might enjoy hearing about?

Sunchokes. Or, Jerusalem artichokes they’re also called. They’re really tasty. They’re small little tubers, I didn’t know much about them until I started researching this book, but then I planted some in my garden and they completely took over my garden bed. They’re very vigorous! When you roast them, they get kind of sweet.

Wait, they’re tubers like potatoes?

Yeah. They kind of look like little ginger roots — they’re knobby, and like, not that great-looking. They look kind of lame and ugly. But I think they’re really tasty, and they’re really good for you.

Cool. I will definitely go get some of those. Are there nutrition books that have been especially influential for you?

Yeah, the biggest one while I was researching my book was by two gut microbiome and immunology researchers at Stanford: a husband and wife team, Erica and Justin Sonnenberg. The book is called The Good Gut: Taking Control of Your Weight, Your Mood, and Your Long-Term Health. It’s great. I met with them when I was reporting, and I got to hang out and eat lunch with them at Stanford. They have excellent, excellent science and recommendations, and they have good recipes in there, too.

There was a Justin Sonnenberg quote in your book that captured my imagination. Where he describes how the microbes in our gut — the ones that are permanent microbes, essentially — are the result of endless microbe-passing-down from generation to generation.

Yeah.

For whatever reason, what stuck out to me the first time I read it was that when you have a baby with somebody, you’re not just combining genes but — from my understanding at least — you’re also essentially combining your own microbiome with theirs, into this third additional person: the child. Is that accurate?

Yeah, I mean to a certain extent. I’d say that the baby would get more of its microbes from the mom.

Right.

Just by virtue of — especially with a vaginal birth. And the birth process. But yeah, that is a good way to look at it, I hadn’t thought about it that way.

I’m not sure why that stood out, I guess it’s on the brain, although actually as I was saying it out loud just now, I’m like, Does this make any sense?

Well, there’s actually been some really interesting research on generations of mice in the lab, looking at what happens when mice decrease their fiber intake. When they eat less fiber, each generation of mouse will pass on fewer microbes to their young. So that’s kind of interesting. It’s still developing, and it doesn’t necessarily translate to humans, but it’s a pretty strong signal, I think, that we are, over the generations of eating less fiber and doing other bad things to our microbiomes, also passing along these impoverished microbiomes to our kids. And to all future generations.

That’s really interesting.

But there’s more of that in the book!

This is sort of silly, and maybe not even accurate now that I know more about what fiber does, but do you like thinking of fiber as the digestive system’s toothbrush? I’ve seen that a bunch of places, and I don’t know if having spent more time thinking about it there’s a parallel you prefer more.

I think that’s a great, kind of mechanical way to look at it, in terms of fiber’s function throughout the digestive tract, especially in the lower intestine. But fiber does so much more than that, I would actually look at it more as the nourishment for our microbes. The nourishment that they need.

Right.

And really — well, it’s kind of a cool way to think about eating, too. This came up in a conversation with the Sonnenbergs, actually. They have two daughters, and they talk all the time with them about eating healthily, and about eating lots of fiber. They’ll present eating fiber as “I’m not just eating the bean salad for me, I’m also eating it for my microbes, and isn’t that cool? To sustain this other life that’s also helping me?” So, that’s kind of a bigger-picture way of thinking about food.

That’s great. So, it’s sort of like having an internal pet, or many tiny internal pets. Was there ever a time in your life when you made a significant change to the way you eat? Based on something you learned?

I’d say that doing the reporting for this book has definitely changed the way I eat. Because I definitely am more mindful about eating more kinds of fibers and whole foods, and also just incorporating more wild fermented foods in my diet.

Sorry — what is a wild fermented food?

Oh yeah, sure! There are kind of two categories of what I would say are microbe-heavy foods. There are foods that are intentionally cultured, with specific strains, like yogurt or cheeses, or kefir. But then there are other foods, which are generally pickled foods, like kimchee, sauerkraut, or pickles, that spontaneously ferment with the microbes that are in the environment and that are on the foods. And those pickled foods tend to have more diverse microbes in them. Especially a food like kimchee. There are crazy amounts of different microbes in kimchee.

Do you make your own?

Um, no. I don’t. I mean — I don’t make my own kimchee, but I’ve made other fermented foods, like sauerkraut and pickles and that kind of stuff.

I tried to make sauerkraut once — actually I very successfully made sauerkraut once, and then I made it very unsuccessfully another time.

Ha, yeah. My last batch was really great, and I’m nervous that I won’t be able to replicate it.

Yeah, I took it for granted that it was just going to happen so easily again — but the bad batch had like, syrup in it as well as bugs and larva and stuff. It was horrible.

Oh no, that’s pretty rough.

But that was like two years ago so it’s worth trying again.

Definitely.

This conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.