I got sober out of spite. I also got sober out of wisdom and courage and rationality and sadness and loneliness and boredom and desperation, a vague desire to be a wife and a mom, and — especially — because of a book, but, deep down, part of it was because I wanted to prove someone wrong. To “show” them. To “make” them “sorry.” I had recently been in an argument, which was also part of a long-standing fight about what I should be doing with my life and whether I drank too much, and I kept losing the fight because it was always true that I did drink too much. And to a certain extent it felt like this was a fight, along with others — maybe all others — that I’d never be able to “win” if I kept drinking. Like I’d be permanently hamstrung if I kept drinking the way I did. And maybe if I kept drinking at all. I’d be permanently vulnerable on this one front. Someone could always trump me with, “Well, I’m worried about your drinking,” and it would always be true.

So a part of me used that kernel — the kernel of spite, a desire to win — to get me from there to here, drunk to sober. The spite was like training wheels. And then the bigger and better reasons took over, but the first day, the first night (the first hour? I don’t actually remember so well), it was galvanizing to think, “Finally, I’m going to win that fight. I’ll never be vulnerable to attack on this front again.” In hindsight, this was a faulty line of thinking, because the person I was arguing with also wanted me to get sober, and I didn’t “show” anyone or make anyone sorry — the people who cared about me were relieved by my sobriety. But in the moment, this impulse worked well. Use what works.

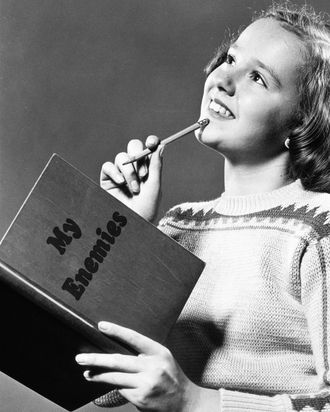

If you’re anything like me (filled with fear, hatred, spite, and a desire to win) it can be inspiring to envision yourself as the winner and think of someone else as the loser. To imagine a future where you triumph and an enemy is crushed. Or at least, it can sometimes be more heartening than trying to make a big change because it’s “right” or “better.” Or, it can work when you’ve already tried making the change for those “good” reasons, and it didn’t really stick. There are dark and light powers to harness when trying to make changes, and sometimes you have to harness them both.

For instance, the word “better” is sort of vague and sounds nice (“I’m becoming a better person”), but I’ve found that “superior” can sometimes be more powerful, since it indicates a loser, too. Sometimes it’s important to have a loser in mind. It’s more fun, it’s also a little darker, and it’s more powerful. It’s sort of a zero-sum-game mentality — for me to be superior, someone else has to be a little bit inferior. It works best when you envision your old self as being the loser, and your new self as being the winner, but sometimes another person (an enemy) can work just as well if not better.

This works for all sorts of habits — smoking, drinking, overeating junk. Think of the people who will be hurt by your newfound power and ascendence, your visible improvement, and it can sometimes be easier to make the change, to adopt the new habit or routine. Think of your enemies and how disappointed they’ll be by your moving up in life; it can be very exciting. Later it may all turn out to be nonsense, but you’ll be on the other side by then.