This collection of Bill Cunningham’s street photography, edited by Tiina Loite, is the first volume drawn from his vast personal archive. It contains images that originally appeared in the New York Times, where his popular “On the Street” column ran, beginning in 1985, as well as many, many more that he published earlier, in magazines like Vogue and Town & Country, and then filed away for future reference. In cases where an individual captivated him over a long period of time — such as Anna Wintour, whom he first noticed in the early 1970s when she was an unknown junior editor in London — you may assume that some images have never been seen until now. Even those that appeared in the Times are being seen anew here, outside the spatial confines of the paper.

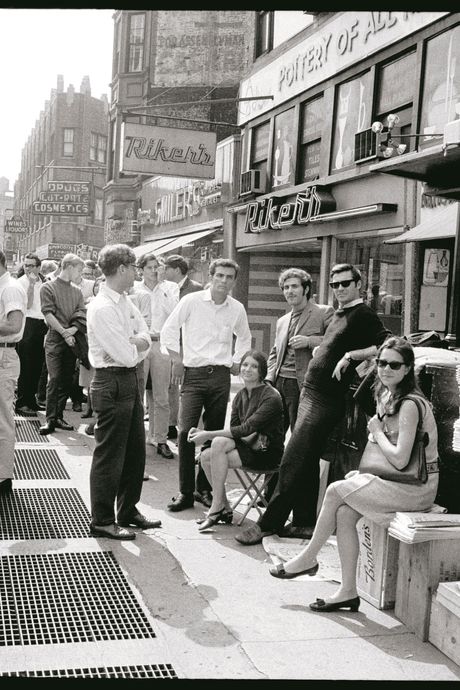

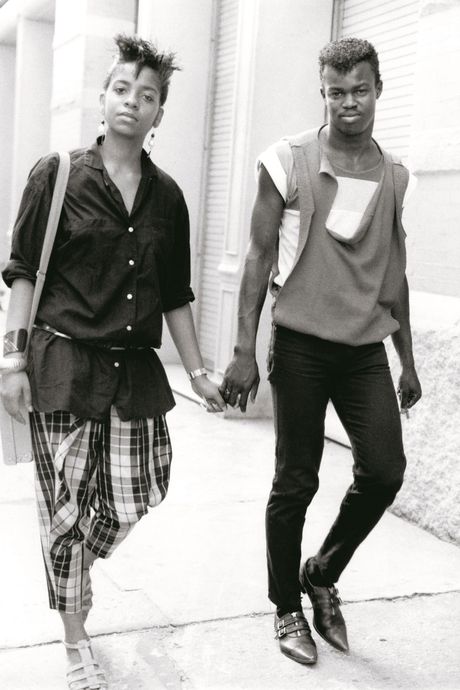

As we move from decade to decade, starting in the 1970s — around the time when Bill’s photos began appearing in the Times — through his death in 2016, you’ll see the evolution of style, of trends, and of the everyday, both in New York City and in Paris, Bill’s two favorite places in the world. The book also highlights a few fascinations Bill carried with him always, including his muses, urban dogs, and, of course, people wearing hats — a nod to his early career as a milliner.

Bill was prolific indeed. In addition to his street work, most weeks he managed to shoot between 15 and 20 parties, which he featured in his “Evening Hours” column on the page facing “On the Street.” The result was an up-to-the-minute, kaleidoscopic report on the changes in fashion as observed by a man who missed almost nothing. He chronicled the first wave of women to ditch their heels and commute to work in sneakers, the return of the zoot suit, the phenomenon of low-riding jeans, the vogue for camouflage, and a hundred different ways New Yorkers stylishly brave a storm. He believed that a true portrait of fashion — and, by inference, the times — depended on seeing how real people dressed, whether kids in deconstructed sweatshirts or big spenders at a charity event. The runway wasn’t enough, so he hit the streets every day with his camera.

Such dedication, along with the spartan way Bill lived — in one of the last bohemian apartments above Carnegie Hall, surrounded by battered filing cabinets, sleeping on a cot supported only by milk crates — earned him enormous admiration and respect. At the same time, this man who noticed everything was himself dressed purposely not to be noticed, in khakis and a series of ill-fitting blue smocks he picked up for a few euros on his trips to Paris for the collections. He was perfectly charming but full of demurrals. He appeared secretive about his background. (For years, the assumption around the Times was that he came from a rich Boston family, in part because he seemed to know every blue blood since the Mayflower. But in reality, he was a son of a postal worker and a homemaker from suburban Boston.)

On the rare occasions when he did talk about his photography — or, anyway, was asked — he made it sound amateur, calling it “bottom of the barrel” and insisting he wasn’t a real photographer at all but, rather, a “recorder.” Whether or not Bill was obeying a higher law and guarding his creative methods in order to keep his mind free, all those qualities — the diffidence, the humble garb — fed into his mythology. To an extent, that’s what we got in the interviews he gave late in his life, in the Times and The New Yorker, in the well-received 2010 documentary Bill Cunningham New York, and in the 2018 documentary The Times of Bill Cunningham, drawn from an extended interview he gave to a reporter in the mid-1990s.

But with the opening of his archive, we have gleaned a different view of this remarkable man. It’s not that the earlier portraits were inaccurate; they just weren’t complete. Among his papers was a memoir of his childhood in a Boston suburb and his first career as a milliner in New York; he designed hats between 1948, when he moved to the city, and 1962. Published in 2018 as Fashion Climbing, the book shows that Bill was anything but diffident. He was nervy and ambitious. He was a party animal! He posed as a waiter — complete with a napkin on his arm — to sneak into a couture show. He sought out and befriended the two women who owned Chez Ninon, the Park Avenue shop renowned for its quiet taste and roster of society clients, including Jacqueline Kennedy. He cold-called Hubert de Givenchy, one of the biggest names at the time, and was actually granted a meeting. And if none of that blows your mind, he shared his first apartment at Carnegie Hall, a duplex, with Norman Mailer and his third wife, Lady Jeanne Campbell.

So much for the oblate of Seventh Avenue. As a youth, Bill was so confident about the life he wanted — a life at the innermost part of the fashion world — that he didn’t allow even his conservative parents’ shaming, the beatings he received when he tried on his sisters’ dresses, to get to him. (And despite how he left things in the book, Bill, a devout Catholic, maintained close ties with his parents until the end of their lives. In the late ’70s, according to his niece, Trish Simonson, he spent two weeks with them every summer at their cottage in Duxbury, Massachusetts.)

The writer Louis Menand once said about the problems of writing a history, “You are almost completely cut off, by a wall of print, from the life you have set out to represent.” These words feel true of Bill and the import of his work. It’s been blocked behind a misty wall of unexamined information. Paradoxically, his archive helps let in some light.

I visited the archive with Tiina. I was curious to see the files for myself. What immediately stood out was how far into the future Bill could see. In the memoir, he boasted of having extra-long antennae for anticipating the fashion mood and that this feeling pushed his creativity as a milliner — sometimes over the edge. For his final collection, he did space helmets: “naked of trimming, just pure shape, molded like the cones of rockets and racing headgear.” That was two years before André Courrèges’s futuristic simplicity dominated the fashion world.

The point is, Bill acted on instinct, and once he moved into journalism, in 1963, and later photography, in 1967, this instinct served him similarly. That he picked out Anna Wintour is one indication. How did he know, beyond the fact that she looked adorable in the clothes and was the daughter of a prominent journalist, that she was someone special to watch? He just did. Moreover, he kept feeding her file, so that over time, he held a comprehensive visual record of one of the most fascinating people in fashion. But there are other clues, in his files and elsewhere. Bill excelled at journalism from the start. When he sensed that the convention of hat-wearing was dying, he closed shop and joined Women’s Wear Daily, the trade publication, and also added freelance gigs with a few regional papers. By 1966, he was the Chicago Tribune’s “roving fashion reporter,” based in New York.

In preparing this introduction, I decided to read his reporting at the Tribune. It was astonishing. Between 1965 and 1969, he covered virtually every major event and personality in what was a very happening era. He wrote about underground movies, Electric Circus, Max’s Kansas City, the Chelsea Hotel (“the most ravishing array of creative folk in all New York”), Andy Warhol, Halston, Joan “Tiger” Morse’s famous loft party, Diana Vreeland, Betsey Johnson, and Happenings. (After reading his lively if somewhat subjective accounts, I wonder if he didn’t pen his secret memoir around the same time.)

The idea of him taking pictures was almost a stroke of luck, like so much else that happened to Bill. In 1965, while in London, he met the photographer David Montgomery through their mutual friends, the illustrator Antonio Lopez and his partner, Juan Ramos, who also lived above Carnegie Hall. When Montgomery came to visit Lopez the next year, he noticed that Bill, who at the time favored fisherman knit sweaters, was furiously scribbling notes on a pad.

“I said to him, ‘Why bother doing that?’” Montgomery, now in his 80s, recalled. “‘Here’s a camera. Use that.’” The camera was an Olympus Pen-D half-frame. About the size of a pack of cigarettes, it could shoot 72 frames. “He picked it up pretty good,” Montgomery said, adding, “The thing about Bill was, when you look at the photographs, they’re right in the core of the matter.”

Because of Bill’s background in fashion, his instincts, and, frankly, his ego, his pictures assumed an authority equal to his writing. He didn’t publish his pictures, at least not in the Tribune, until 1967, and the subjects were mostly fashion shows and VIPs at events. That year, he photographed a charity show featuring Givenchy’s collection. His thrill at being allowed to shoot backstage — a big deal then — was right on the surface, as he noted in his story: “Givenchy, who usually runs from the camera, allowed … the photographer” free rein.

Bill began shooting for the Times in the mid-’70s, though he continued to freelance for magazines, and in 1982 he helped launch Details. Freedom was important to him, and he didn’t join the Times staff until 1994. As he once said, “Money’s the cheapest thing. Liberty and freedom is the most expensive.” In the tradition of early-20th-century street photographers, notably Jacques Henri Lartigue and the Seeberger Brothers in Paris, who photographed fashionable women at racecourses or promenading in parks, Bill positioned himself at busy shopping corners, like Fifth Avenue and 57th Street, and outside chic restaurants. Le Cirque was a favorite. It was there that he snapped photos of socialites like Blaine Trump and Pat Buckley, and on another occasion Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger. His files from the ’70s and ’80s are absolutely saturated with the glamour of that era. It helped that he plainly knew where the action was — whether it was the allure of Yves Saint Laurent and his gang or the scene at Studio 54. He also annotated his files — again, with foresight — by including press clippings of the events. When the couturier Charles James died, in 1978, Bill went back to an image he had shot two weeks earlier at Studio 54, and recorded that it was the last photo he had taken of the great man.

This type of imagery seemed to serve as a bridge to the street fashion he shot increasingly in the late ’70s, when the people he photographed were generally unknown — and unaware of the spindly man darting through the crowd with his camera. That may be why his earlier black-and-white images — before the Times moved into color — have an unusual degree of spontaneity.

But the unifying element in all of Bill’s work, from his innovative hats to his searching news reports, to the photographs in this wonderful book, is that the ideas flow forward. As much as Bill savored the history of fashion and its eccentric cast of legends, he never allowed nostalgia to creep into his pictures. To the end of his life, he remained vigorously, joyfully in stride with the times. “Child,” he would say to a middle-aged person, “fashion is about today.” This book represents a lifetime of putting that belief to the pavement.

Excerpted with permission from Clarkson Potter, from the book Bill Cunningham: On the Street by The New York Times Company. Copyright © 2019 by The New York Times Company, photographs copyright © 2019 by The Bill Cunningham Foundation LLC. Published by Clarkson Potter, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.