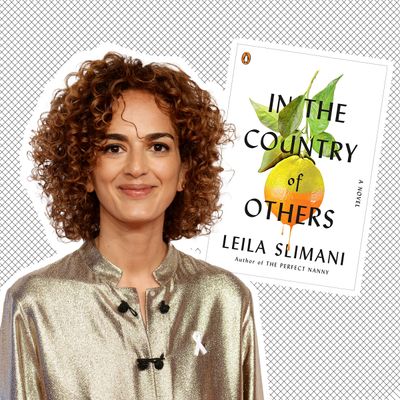

Writer Leïla Slimani has never shied away from complicated aspects of human nature. Her first novel, Adèle, tackled sex addiction, and her second, The Perfect Nanny, won the Prix Goncourt in 2016 for its gripping tale of child murder. Her latest book, In the Country of Others, uses her family history to tell an equally complex story.

The novel follows a young French woman named Mathilde — based on Slimani’s own grandmother — who meets a Moroccan man named Amine, a soldier fighting for France in WWII. When they marry, Mathilde moves from Alsace, France, to a farm in Meknes to start a family. What follows is a story about the complexities of interracial marriage in the 1940s, womanhood in an intensely patriarchal society, and the Moroccan struggle for independence from French colonial rule.

Slimani knew that the task of intertwining her family’s story with that of Morocco’s revolution would be daunting. “I understood that it was impossible to deal with a period of time like colonization without accepting the fact that it was a very ambiguous, very gray period,” Slimani says. “I want it to be impossible to put my characters in little boxes and I want at the end the reader to say, ‘I don’t know if they are good people, but they are real.’”

The Cut spoke with Slimani about her characters’ ugly feelings, how little some people seem to know about Moroccan culture and history, and her mother’s reaction to the novel.

In the Country of Others is the first book in a trilogy, and a huge undertaking of historical fiction. What was your research process like to understand Morocco at that time and to delve into your family’s history?

I read a lot of books, of course. I did a lot of interviews with historians and scientists and also with friends of my grandparents, people who lived in Meknes at that time. I interviewed my family: my mother, my grandmother, and my aunt, about what they could remember.

What I wanted to do was not only to tell the story of my grandparents but to try to express the fascination I used to feel when I was a child and my grandmother would tell me stories about the war and what it was to be a young woman in Morocco in the ’50s. As a child, I found those stories quite fascinating and I wanted to provoke that for my reader. To think: Wow, what a woman to do such a thing! So I tried really, really to remember the feeling I had when I was a child.

Were you at all hesitant to write about your family? Were you worried about how your mother or your grandmother would react to certain scenes or the way you portrayed their lives?

Of course. I’m maybe even more worried now with the second part of the [trilogy] that is about my parents. But I think that when you write, you have to deal with that all the time. You are worried about a lot of things. Would people understand what I tried to write? Did I do exactly what I wanted to do? You have to accept that. For me, the most important thing was that my mother wouldn’t feel betrayed and that she would give me some boundaries. She told me: “I don’t want you to talk about this or about that,” and I respected that and when I finished the first part, I gave it to her and told her: “If you don’t want me to publish this book, I won’t.”

I think that literature is very important, but my mother is even more important than literature. I don’t want to make her sad, so yes, I gave it to her and said, “Okay, what do you think?” And she told me, “I have no words. I can’t tell you what I think. I can’t tell you what I feel. One day, I will write you a letter and you will understand but you can publish it.” So as long as my mother is okay, I don’t care about the rest.

You describe Morocco very vividly in the book: the vendors, the city of Meknes, the orange trees. Were you in Morocco while you were writing? If not, how did you transport yourself there mentally?

I was in Paris and I have to say that it’s maybe the fact that I was not in Morocco and that I left Morocco for 20 years that made me able to write about Morocco like this. You know, I think the majority of writers write about childhood and we are all obsessed about childhood because we are all in a kind of exile of childhood. We are not children anymore. I think it’s easier to write about something you have left; something you are far away from because nostalgia and remembering helps you write and find exactly what moved you at that time. Sometimes it’s very difficult to write about something when you are looking at it very close. You need some time and some distance.

Is there a way you get yourself into that nostalgic frame of mind when you sit down at your desk to write? Or is it just accessible in your mind?

I think about who I was when I was a child. What it was to smell jasmine for the first time. To taste an orange for the first time. To eat the bread that my grandmother used to make because I know that I will never feel that again. I know that it’s finished. It’s over forever and it makes me feel something very strong to know that yeah, of course, I will eat thousands of oranges again, but they will never have the same taste of the first orange I tasted with my grandparents.

Your book doesn’t shy away from heated topics, like patriarchal attitudes in Morocco, especially in the ’40s and ’50s, and the torment of French colonial rule. What kind of feedback have you received from Moroccan readers? Or French readers? How are people reacting to the complex web of identities that you present in the book?

I received a lot of letters from people who are 70, 80 years old and who used to be colonists in Morocco. Some of them are very violent, telling me that I understand nothing and that French people were always so good to Moroccan people and that I should write a book about the fact that now Moroccan people are colonizing France through immigration and that we are the bad people. So of course, even after 50 or 60 years, you have people who are not very happy with what I write because they think that it’s not the truth or not their truth. When you are a writer you have to accept that everyone thinks that he holds the truth and that he knows exactly what happened and how it was like.

How does it feel to get responses like that? Is it hard not to take it personally?

Sometimes I get very angry, yeah. Three months ago, I received a poem from a man, a crazy man — a very racist and Islamophobic poem about Moroccan people coming to France and destroying civilization. But you have to be quiet and not answer to this kind of thing because I’m not going to convince him. He’s not going to convince me. I have to accept that some people will believe that and that’s it. You try to write a book, you try to do things, if he doesn’t want to understand, I can’t do more than writing a book.

What do you think is most important for readers to take away about Moroccan history, particularly post–WWII?

I’ve been very frustrated these past years because after September 11 and after all that happened with the Islamists and terrorism, a lot of people in the Western world, in France, in Britain, everywhere — they have the feeling that they understand everything about Islam, about the Arab world. They speak about this and about that and very often, I feel people know nothing about my country, my culture, and my civilization.

I’m betrayed by the Islamists that are betraying my culture and my religion and at the same time, I feel that all the racists, all the people from the extreme right in the West, also despise my culture. In a certain way, I want to tell them it’s not that. It’s not the Islamists or what the extreme right are saying. We are complex. We are not only Muslim. We are citizens. We have a history. We have a sociology. We have a lot of things to say, to express, and to give to the rest of the world. We are not only victims. We are not just bad people wanting to immigrate and to colonize the West. You know, I’ve read a lot of books from Britain, from France, from Russia. I know a lot of things about your country, about the U.S., and at the same time, I feel that people don’t know about my country and my culture. I want to tell them that we also have a lot of stories to tell and women in our countries are not only women with a veil waiting in the kitchen for life to happen. It’s much more complex than that.

Something that I really like about all of your novels, but particularly this one, is how you don’t shy away from emotional ugliness. I was struck by how many perspectives we get in the story, how we see the cruel thoughts Mathilde has about Amine and vice versa. Despite their loving relationship, they can be racist and sexist toward one another. Why was it important to you to write their characters this way?

When I began the trilogy, I understood that it was impossible to deal with a period of time like colonization without accepting the fact that it was a very ambiguous, very gray period. I don’t want to write a book that is black or white and to say: “Those are the good people and those are the bad people.” I think that the aim of literature is to try to say that life is complex and that very often we don’t know what to do. We try to do the best we can and we fail and we do wrong and at the end, we regret. Sometimes we are good people and at other moments, we can be racist or sexist or envious or have bad thoughts and it’s about that that I want to write. I want to write about people that are just human. I want to write about people that are not in little boxes. This man? Maybe he is a colonist but maybe, at certain times he’s also a good person. Maybe this man is an Arab and he’s a hero but sometimes, he’s a very bad person because he’s beating his wife or he’s cheating on her.

I also noticed the complicated negotiations around power in the book. In certain scenarios characters have more power or less. For instance, Mathilde is white, she’s European, but she’s also this in new foreign land, and she’s a woman. There are these complicated identities. How did you try to portray those differences in power and regulate them scene-by-scene?

I think it’s something I’ve been obsessed with since I was a child, because I hated being a child. When you’re a child, you have to obey all the time. You are dominated. You don’t have free will. People tell you when to sleep, when to eat, how to dress, they tell you to shut up. I was a girl, so I had to obey even more and I was living in a very patriarchal society in Morocco where you have God, the king, your father, and then at the bottom you have yourself. So I think that very young, I understood that everything has to do with domination. Who is dominating you? Who do you have to obey and why? Very often I felt it was so arbitrary. Why do I have to obey that? I know what is good for me. As a woman, as a Moroccan, I wanted to write about that.

My grandmother, I found her fascinating because she knew that she sometimes had to obey if she wanted to live in this society and be integrated into this society, but she would always find a way to find a certain freedom. For instance, she loved to use very rude words and she loved to tell us stories and songs that were very rude in secret in her room and I loved that. I tried to express that about my grandmother and I tried to show that at that time, a woman like my grandmother — but also my grandfather — could feel domination through humiliation. As a woman, you are humiliated by men. As a white woman who had married an Arab, you would be humiliated by white women looking at you and saying, “Ha! Look, she’s married to an Arab and she’s pregnant with an Arab man.” And of course, as a Moroccan man, you would be humiliated all the time, by the colonists but also by the fact that your country is not even your country and that it’s the country of others.

When I was a child, I was living in Morocco and I remember that people would always say about Morocco, “Ah, you’re living in an underdeveloped country.” People would say, “Ah, you’re an Arab. They want to live in the West. They want to live in Europe.” I felt very humiliated and I think that’s also why I want to write this trilogy. I want to understand why it is so difficult to be proud when you come from a country like my country. It is a small country, it’s a country that is colonized, a country where a lot of people want to emigrate. How can you build your pride when you come from a country like that? Especially when you’re a woman.

Have you started working on the next books in the trilogy?

I finished the second part. It’s going to be out in France in February next year.

What can we expect from the next two?

Disaster [laughs]. No, I don’t know. Most of the book is set during the summer of ’69 and I wanted to show that even if a lot of people see Morocco as a Muslim country, the country of camels and princesses and all that, it’s also a country where you had a lot of hippies, where Jimi Hendrix spent the summer of ’69, and people were [taking] drugs and [throwing] a lot of parties and making love. It was a very free and beautiful time in Morocco and just after you had terrible repression during the reign of King Hassan II. I wanted to show that — the confrontation between the immense desire for freedom and for love and for happiness and the repression of the king.

Do you have plans for the third and last book?

Yeah, the last one will be more about my generation. It will begin in 1999, just before September 11, and it’s about all the young Moroccans going to France or the U.S. to Great Britain, about immigration, and of course, a lot about terrorism and the rise of Islamists.

French president Emmanuel Macron appointed you an emissary of Francophone affairs — you’re a diplomat now! The role has historically been occupied by politicians, but you’re an artist promoting the use of the French language. How did that play on your mind while you were writing?

When I was writing the second part, it was very important because I’ve always asked myself: Why do you speak French? Why do I write in French? My name is Leïla Slimani, I was born in Rabat. My parents are Moroccan. I think that’s also why I want to write this book. Why do I speak and write in French? Why do I dream in French? Why do I feel French even though I’m not French? What is my connection to this country? My grandmother was French, but she became kind of Moroccan at the end of her life. I wanted to show that you can be two things at the same time and that it doesn’t have to be a conflict. It doesn’t have to be violent and difficult. You can be Moroccan and French. You can be a Muslim and believe in democracy and believe in the respect of every religion. You can speak French and not be considered a traitor to your country, or your religion, or your culture.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.