The day I was born, my parents were robbed. It was a warm January morning in 1988 when my father went out to the car and found the window smashed, their cassette player, their Fleetwood Mac and Eagles tapes, gone. They told me later that they didn’t care; their first child had been born. Other than that, my childhood growing up in Hyde Park, one of the most ethnically diverse neighborhoods of Chicago, was uneventful. In the summers, I played soccer in the midwestern heat, then cooled off with strawberry ice cream my grandfather bought from the corner store when he visited from India. On the Fourth of July, the smoky smells of barbecue filled the air while I joined the neighborhood parade, American flags fluttering from my bike handles. I watched with wonder as the night sky popped with fireworks reflected on Lake Michigan. I remember the cicadas singing on hot nights and how the cool lake breeze made the little hairs on my brown arms wave.

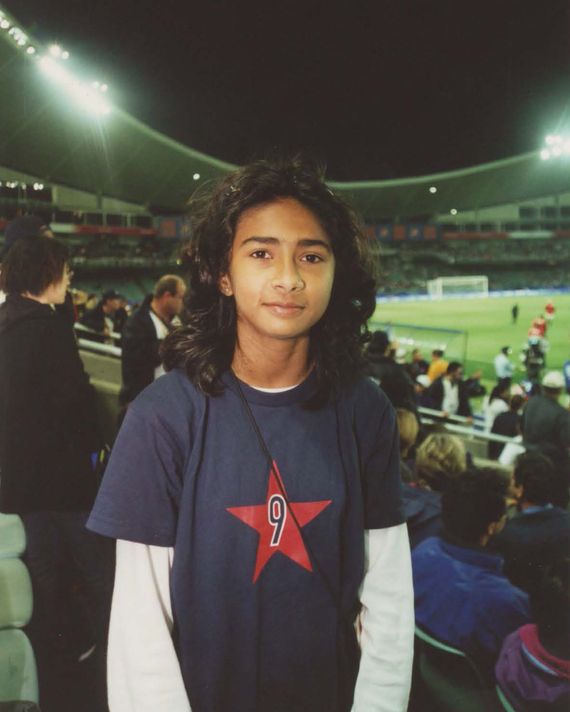

Sports were my obsession, so I was ecstatic when my dad took me to the 2000 Summer Olympic Games in Sydney. I rooted for the U.S. to win gold in every event. My face painted in red, white, and blue, I held my hand to my heart when the national anthem played. After soccer player Mia Hamm high-fived me, I didn’t want to wash my hands for days. When Team USA won the most medals, my 12-year-old body swelled with pride. We were the country to beat.

Then 9/11 happened. I was in band class assembling my oboe when our teacher came in late. He said a plane had crashed into the World Trade Center in New York. The principal wheeled a TV set with bunny ears into the cafeteria. We watched a plane fly through one tower, then a second plane fly through the other. When the first plane hit, we thought it was an accident. When the second plane hit, we knew it was not. We watched this on repeat all morning.

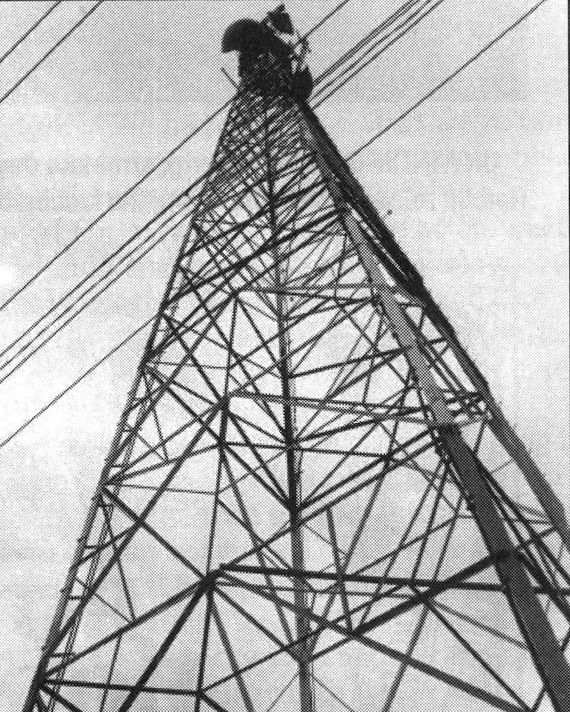

As the U.S. went to war on terrorism, I went to high school and found a new passion in photography class. From behind the lens, the world was mine to explore. I found I could express myself in ways that I couldn’t with words. I took my camera with me everywhere. One Sunday, on the way to a soccer game, I spotted inspiration for my “abstract objects” assignment and asked my dad to pull over. I got out of the car with my camera and focused the lens on a giant metal tower that seemed out of place in the burnt-yellow fields. It looked like an alien. I took a photograph.

Later that night, the phone rang. When my mother picked up, the caller identified himself as a detective from the DuPage County sheriff’s office. He said they had received a call from a ConEdison employee who saw a girl of Middle Eastern descent taking photos in front of a foreign car. The license plate was registered to our phone number.

“We’re from India,” my mom replied. I heard her explain my class assignment. “Did she break any laws?” she asked.

The detective told her he was just following protocol. Then he wished her a good evening and hung up. It was a troubling call, but we moved on. I developed the photograph in the school darkroom. It wasn’t a masterpiece, but I always felt a rush when chemical magic revealed the images from my teenage life. The darkroom felt safe, like home.

A week after the detective’s call, our monthly housekeeper heard forceful knocks on my family’s apartment door. When she answered, an FBI agent flashed his badge.

“Do only four people live here?” the FBI agent asked.

“Yes, a family,” she said.

Unsatisfied, he searched the apartment. He checked each room and closet and left his business card from the local FBI Joint Terrorism Task Force. He didn’t show a warrant or have my parents’ permission to enter and search our home. He had something far more powerful: the USA Patriot Act.

Immediately after 9/11, Congress enacted the “Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism” law. The Patriot Act sought to uncover terrorists that might be in America, ones that were “homegrown.” I remember reading about this law in class but never expected it would impact my life.

The FBI launched an investigation. My parents were asked detailed questions about their visa status and to provide proof of my school enrollment. They contacted my photography teacher and principal to verify us and our intentions in America. As a teenager, I never spoke directly to the FBI agent, but if I had, I would have told him I was afraid of terrorism too.

When word got out about the investigation, my high-school newspaper reported on it. The student journalists reached out to the DuPage County detective for comment about whether this was a case of racial profiling. The detective claimed that police security measures are blind to both age and race. “All complaints about suspicious activity are investigated like crimes,” he said. “To take this particular crime at face value is ludicrous,” he added. “There are teenage and child suicide bombers in the Middle East. Though it seems less likely to happen in America, there is still a good chance that suicide bombings or terrorist action could happen anywhere else.” My classmates, soccer teammates, and teachers were enraged. They rallied behind me, offering to defend me to law enforcement. While I appreciated their support, I felt embarrassed that I had caused the investigation. I wanted the whole thing to go away.

After that, my fear took on new dimensions. I was not only afraid of terrorism but also afraid to be seen as a terrorist. I was afraid of not belonging or not seeming American enough despite being born in the United States. Perceptions of people who looked like me had changed. My mother’s sweet, lyrical voice, which filled our home with joy, became more somber. She worried about future misunderstandings regarding our name and ethnicity. My parents applied for U.S. citizenship so they would never be questioned about their status again. Proving our Americanness became a necessity to ensure our safety and security.

I wanted to return to my old life, especially the darkroom, but it didn’t feel like home anymore. I worried about taking photos outside of my neighborhood. Whenever I was asked what I was doing with my camera or where I was from, my stomach churned and my mouth went dry. Photography stopped being my passion for a long time. I tried new hobbies and a different career path but never felt the same rush. It took over a decade for me to return to it and pursue a career as a filmmaker. Eventually, I learned that being unafraid to make art is a way to fight the forces of alienation that make people like me feel as if they don’t belong.

The FBI investigation didn’t ruin my life. But it had an effect on me and still does to this day. It was my coming of age, my self-discovery about the challenges of being a person of color in America. Before the investigation, I believed that the country’s values of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness applied equally to everyone. I didn’t know my skin color could be perceived as dangerous. The Patriot Act enabled a new version of fearmongering, making many Americans feel unwelcome at home. This culture of fear and divisiveness has only increased in recent years. Almost two decades later, I still feel uncomfortable in places where there aren’t many people who look like me, where we’re viewed as “other” by our fellow citizens. Many Americans face similar challenges every day with far worse consequences. While I have been fortunate in many ways, I never forget that to walk through America without fear is a privilege that is not our birthright as people of color.

It has taken time for me to confront my naïve perceptions and untangle my definition of home from a country or national flag. I still don’t have a good answer for what home means to me. For now, it may only be a feeling. Fleeting memories that bring warmth and peace, like the sweetness of strawberry ice cream, cicada songs on hot summer nights, and cool lake breezes that made the hairs on my brown arms wave. Or maybe, home simply lies within the edges of my favorite photographs, the preserved moments I choose to carry forward.