When I first came out in the 1970s, lesbians gave each other meaning in private. Everything outside that bedroom, small apartment, tiny dance floor was signified by disrespect, punishment, and exclusion. The one upside, aside from being with women, was that I didn’t have to have get married and have children. I was born in 1958, Eisenhower was president. Women were supposed to get married and have children. I am sure that my own mother never had a real choice, it was so expected it was unquestioned. Now I was free.

Nuclear Family, the HBO documentary series concluding this Sunday, centers one couple who created their dream of a traditional-while-lesbian family with children. In 1976, when Russo and Robin first fell in love, the operative dyke discussion about parenting was the heartbreaking, infuriating, cruel injustice of gay women losing custody of children they had given birth to in the context of previous heterosexual marriage. Ex-husbands and grandparents used the courts to brutally seize children on the assumption that lesbianism itself made mothers unfit. From the vindictive husband of poet Minnie Bruce Pratt in Fayetteville, North Carolina, in 1975 to the mother of Sharon Bottoms, a grocery-store clerk from Henrico County, Virginia, in 1993, women lost court cases and had their children forcibly taken away. One of the early civil-rights organizations formed out of emerging lesbian consciousness was the Lesbian Mothers’ Defense Fund, based in Seattle. As more women came out, more children were seized. From 1976 to 1980 the Fund assisted over 400 lesbian mothers under threat.

While some lesbians wanted to give birth, the early discourse about alternative fertilization was smaller and more tentative than the dominant threat of state seizure of children. Lillian Faderman, the historian, had a child with her female partner in 1975 through a then-evolving underground method of using sperm from a gay male donor to impregnate at home. In a way, this DIY approach was in a behavioral trajectory from the previous era of illegal abortion networks, and the emerging Feminist Women’s Health Care movement that looked to bypass the hostile institutions of power in order for gay women to be able to have the lives that we wanted and deserved. So when Russo and Robin decided to find two gay male donors so that each of them could give birth to a child, they did it outside of the law, because their relationship was outside of the law. And lesbian empowerment required avoiding the state.

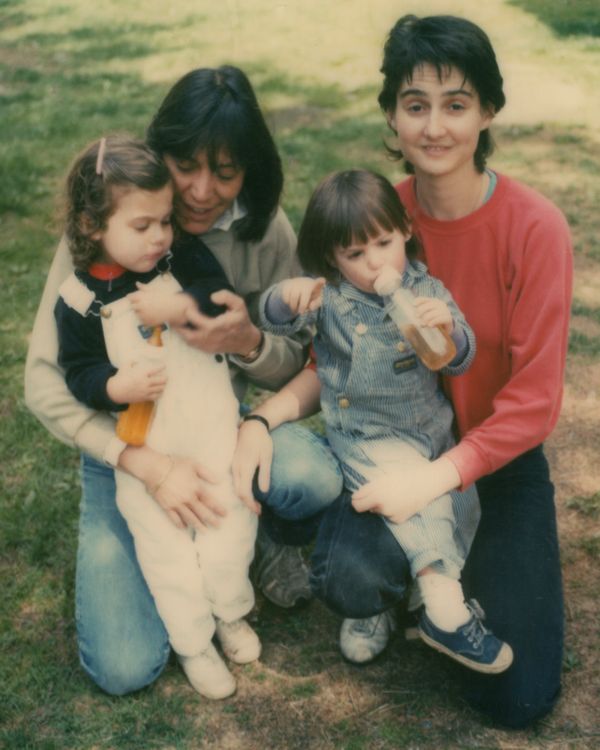

As Nuclear Family tells it, a mutual friend, Cris, introduced this New York couple to one donor and their daughter Cade was born. Then Cris introduced them to Tom Steel, a gay San Francisco attorney. They met briefly and liked each other. The couple explained that there would be no rights and responsibilities. Tom agreed, and soon a second daughter, Ry, came into the world. Each woman gave birth to one child. At this time, of course, not only was there no legal gay marriage, but only the birth mother was considered to be the real parent in the eyes of the law. Although Russo and Robin emphasized the equality of their parenting to both girls, this again was a willed creation of a mutual reality that countered the false and degrading lack of meaning imposed by both law and custom.

The willpower needed to imagine one’s partner and respective offspring as a “nuclear family” was intense. And as lesbian parenting became more popular in the 1980s and 90s, the ability for couples to maintain that parallel agreement was sorely tested. As these new couples produced new children, breakups offered the nefarious opportunity for birth mothers to manipulate the lack of legal recognition to deny their former partners access to children they had raised. In my own circle, there was a couple of ten years, C and A, who had — like Russo and Robin — each birthed one child that they both raised. But when they split up, C exploited A’s lack of legal rights to deny her access to the child they had conceived and brought up but that C had birthed. I remember saying to C, “What you are doing is wrong.” And she replied, “I don’t care.” This behavior became so widespread that Kate Kendell, then the director of the National Center for Lesbian Rights, had to speak out publicly against the tsunami of lesbian birth mothers claiming retroactively that because of the lack of legal recognition, their relationships had not really existed. It was the confrontation of Lesbian Reality with the unforgiving hammer of the state. It was … oppression. Even more reason for ongoing parenting couples to tighten the noose around their created concept of family. The threat was from everywhere, including potentially within.

As Cade and Ry got older they became curious about their donors, and Robin and Russo started to invite the two men into relationships with their biological offspring, especially Ry’s donor, Tom. A few times a year they shared vacations with Tom, his boyfriend Milton, and Milton’s son Jacob, and most notably made sweet, silly, loving, fun videos of fairy tales and other inventive scenarios, in which the loving, adoring relationship between Tom and the girls is documented forever. The power of these videos is evident in Nuclear Family, which is directed and written by an adult Ry, now a mother herself, and which investigates what unfolded from this idyllic moment on. For the closer that she became to her donor, the more Russo and Robin resented, in fact feared, that relationship. They were the only parents. They did not want the biological relationship to matter and they did not want the emotional relationship to matter. In the fragile structure that they alone had to uphold, Ry and Tom’s love became a threat that felt real given the tenuous legal status of lesbian parents at the time. The legal rights of biological fathers were something that a non-birth mother would never have because of the injustice under which all of these relationships had to exist.

As it turns out, their worst fears did come true. Tom freaks and takes the audacious and supremely unfair step of going to court to sue for paternity and visitation. The family is now about to endure a years-long trauma in which both adults and both children live with the daily terror that they will be separated by force.

What the documentary reveals, though, is that like Ry’s non-birth mother Russo, Tom also could never hold on to those rights because as the final episode, which aired last night, reveals, he is also living under the same unjust system as an HIV-positive person, in danger from the very state apparatus he was trying to wield. In the first decade of the AIDS epidemic, people with HIV died of governmental neglect and indifference that obstructed timely processes toward the current standard of care. It is two kinds of oppressed queer people with two divergent sets of fear, both who love a child, and both of whom had real claims to that child: biological, emotional, by birthright and by authentic relationship.

Ry was never able to ask Tom herself why he sued to be part of her life. Maybe because he knew he was going to die. Maybe because he was a man and thought he should be able to have whatever he wants. Maybe because he was a person who has a reciprocal love with a child. Whatever the reason, Ry’s mothers responded by once again creating their own reality, this time by pretending to the court and to each other that the attachment between Ry and Tom was less than it was, as much as they pretend to the court and to each other that biological relations are meaningless.

This moment of revelation brought me back to my own experience. I have been kept from some children in my own family, through an ever-morphing and changing story to justify the separation. It originated years ago in a manipulation of basic homophobia — and was transformed over time as that vulgar construction became unpopular and then a sign of bad behavior. But I have suffered those imposed separations for decades now, and I can attest to the fact that biological relationships are still relationships. Even if someone benefits from pretending that they do not exist, they do. Ry Russo-Young, the subject and director of Nuclear Family holds the hope that children denied relationships that do exist can grow up and reach out and interrogate the stories they have been told. It is a great tribute to Russo and Robin that once confronted with their daughter’s determination to unearth the real complexities and nuances of her own experience, they loved her enough to listen.