This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

On a frigid January afternoon, Shayne Oliver was sitting in his new studio on the Bowery. Despite the building’s grim façade and the absence of a name on the buzzer, the room was spacious and well organized. Best known for Hood By Air, the exceptionally creative label that scrambled different fashion genres as freely as it did notions of sexuality, Oliver has not put on a show in a while. In 2017, seemingly at the height of Hood By Air’s success, he halted the brand and later partnered with a Los Angeles investor. I had come to Oliver’s studio to see new work as one of the great runway impresarios prepared to return to Fashion Week. And he was as fearless as ever.

This week, he plans to stage not one show but a three-night event at the Shed’s Griffin Theater in Hudson Yards. “It’s literally a music festival, and I’m dressing my favorite people,” he told me. Actually, the first night will be a tribute to his past, including designs he collaborated on with his friend Virgil Abloh; the second will launch his new Shayne Oliver ready-to-wear line for men and women; and the last will be a musical performance. But given Oliver’s long-standing interest in music — years ago, he was heavily involved in a roving party called GHE20GOTH1K, and he recently released new sounds on Telfar TV, the open-access channel started by the designer Telfar Clemens — the whole event promises to be a festival studded with extraordinary-looking people. No one wants sedate from Oliver. “I’m a show queen,” he said.

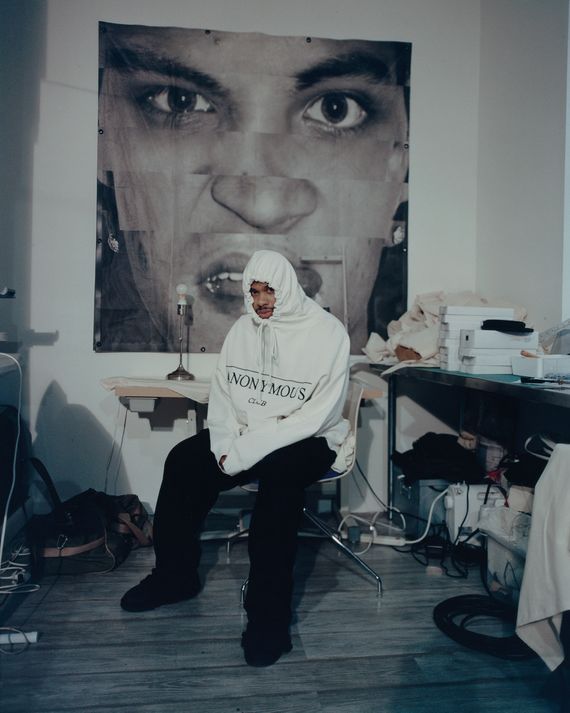

Oliver, who is 33, is tautly built and baby-faced. An intent listener, he often spiked our conversation with “totally” and then came up with another thought or reference. Several times, he mentioned Abloh, who died in November. “He was more of a people person,” Oliver said. “Not that I’m antisocial, but I’m definitely more introverted. I like to be cozy so that I can be more extroverted in my designs. Virgil gave confidence by being more personable — by spreading a web and connecting people.” Oliver had on a white sweatshirt with the logo of one of his new ventures, Anonymous Club, and a pair of jeans spliced up the legs with zippers. Behind him was a rack of toiles, or mock-ups, for his new collection, and on a wall were sketches of clothes and accessories.

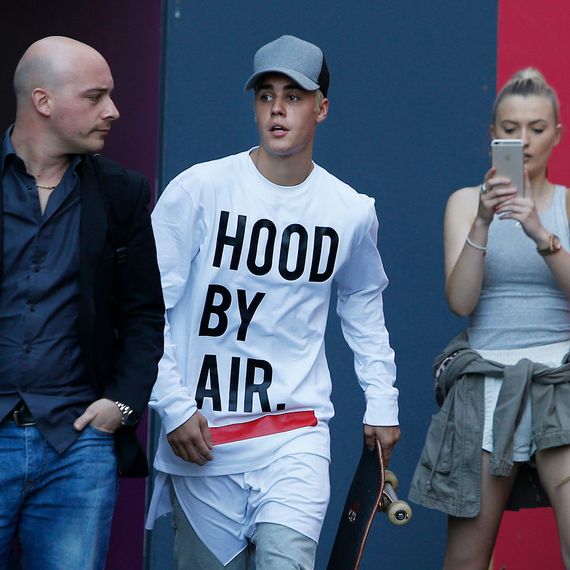

Formally announced a year ago, Oliver’s return — and its meaning for fashion — hasn’t been shrouded in secrecy so much as in obfuscating hype and fanboy lingo. According to various media sites, Hood By Air has a cultlike” following, is “Pan-racial,” and is “a movement” that came “to embody the mid-2000s Zeitgeist.” Although Hood By Air is being revived, its future direction is complicated. For one thing, the brand will now be a streetwear business with capsule collections, rather than a line that revolves around fashion shows. Shows were integral to HBA’s design process, which was conducted by a collective of friends and staff. HBA was renowned for its “family,” which included Oliver’s business partner at the time, the filmmaker Leilah Weinraub, who had joined by 2012 and wore the CEO cap. What happens, Oliver wondered aloud, when there isn’t a collective to spar and shape ideas? Then too, he added, “our ideas may not be the freshest ideas for the Hood of today.” He readily admits that Hood may have “too many ghosts and cobwebs.” In any case, he and his business partner, Edison Chen, have decided to focus on Hood’s streetwear legacy, which is considerable, aiming it at the voracious global youth market.

For all those reasons, Oliver decided to create two new entities in addition to Hood By Air — Shayne Oliver, billed as “a high-concept luxury” brand, and Anonymous Club, which functions as a production studio not only for fashion but for music, visual art, and performance art that Oliver might want to host. That’s the setup for the “music festival” during Fashion Week.

And the clothes?

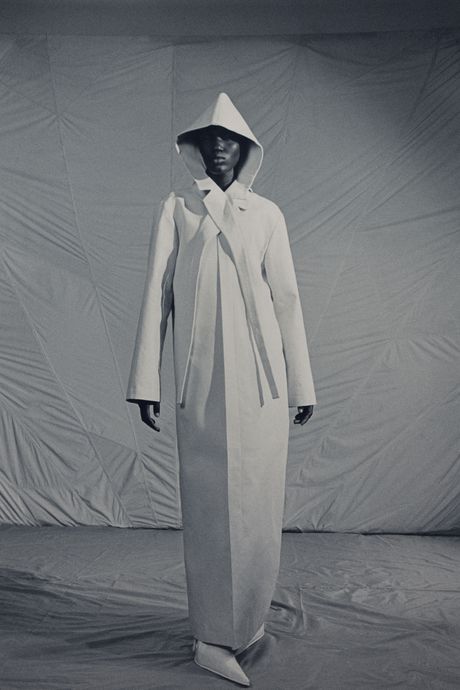

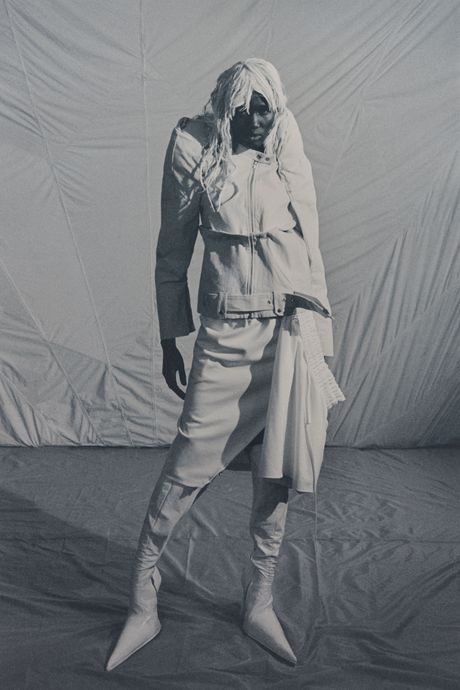

“I’m doing a lot of ball gowns, which are for the people that I’m highlighting during these performances,” Oliver said. “And while that’s happening, I’m going to introduce some more wardrobe shapes. One idea of tailoring, one idea of casual.” Because the clothes and shoes were still in Italian factories, I could only view sketches — and sketches don’t give a full picture of a garment. Besides, styling and models will transform clothes on a runway. Still, the belled shapes on the wall were intriguing and indicated a new direction for Oliver, who hasn’t done this kind of glamour before. As he told me, “Hood was definitely about ripping it apart, and Shayne is more harmonious, about being an adult.” There were also sketches of footwear — stiletto boots with bandage-style strips that recall a classic Hood look, though now with circular openings; formal-looking tennis shoes; and a perfectly seamless pair of platform shoes that seemed decidedly, though not horribly, corrective.

Studying the wall, he said, “It’s this idea of creating strong silhouettes without much definition that I’m focusing on. Just so people understand the kind of strength that I’m into.” He later said, “There’s something really fresh about the way Americans do fake glamour that is even more glamorous than the way Europeans do glamour. Which is also why Vetements was so cool for that moment. Rich kids wanted to look urban. I want to look chill.”

American designers are rarely considered disrupters. True, Marc Jacobs shocked with his 1992 grunge collection and went on to create original work, but his shows don’t make you feel anxious or uncomfortable. Thierry Mugler’s designs in the late ’70s and early ’80s, with their embrace of gay glamour, had that power, but, of course, he was French. For me, only one New York designer has ever raised those kinds of feelings, and that’s Oliver. Partly, it was his models, who looked charismatic and sexually open, and they were always diverse — Black, brown, queer, trans. And partly it was the clothes, which weren’t harsh or crude, exactly, but, in their cut-up, chaotic styling and dark tones, aggressively disdained prettiness.

What is striking, when one looks back at the shows of that period, is the marked change in references after the fall of 2015. The difference is sexual. That season, the clothes were substantially chopped up and appeared to be falling off the body. The impression they made, as I later wrote, was like “a fist to the face.” The next two collections also expressed sexuality, albeit a harsher kind. Hustler leather. An oversize coat in a black protective material with matching pants and waders that weirdly suggested firefighting gear. Gel smeared over the models’ hair and faces. Pornhub sponsored that particular show, and one of the models, casually wearing an open black coat, shorts, and waders, was the photographer Wolfgang Tillmans, whose work has long explored sexual freedom.

When I asked Akeem Smith, who was the stylist for most of Hood’s shows, what he thought Oliver’s strength was as a designer, he replied, “Honoring his references without being disrespectful to the reference. I would say he’s very tapped into his own sexuality.”

Sexuality is fashion’s main “expressive motor,” as the costume historian Anne Hollander has put it. Oliver, in contrast to other contemporary designers, doesn’t present sexuality as a trend: Oh, here’s a bit of bondage this season. He presents it as a lived experience based on his personal knowledge of friends or a community. That’s the respect, and it’s also the source of his singular power.

In 2016, when The New Yorker profiled Oliver — when Barneys put his clothes on six custom-made mannequins in its windows — Hood By Air was carried in some 250 retail outlets. Business had doubled year over year since 2013, and the products were being made in Italy with short-term sales and distribution help from an Italian luxury group. Yet for all the free-flowing creativity, there were profound flaws in the organization, according to Oliver and several others to whom I spoke. “We had grown the business exponentially and then we came back to America and we didn’t know how to do any of this ourselves,” Oliver said. “We had no structure. This is not bad-talking Leilah at all, but a lot of the roles we had were performative. Was Leilah a CEO? No. We all knew each other personally.”

He went on: “The thing that kept me there and created HBA was the hope that everybody knew what they were doing. And I think when that hope went out the door, I stopped believing that she was the CEO, and she stopped believing that my creative direction was viable.” Oliver laughed. “I could be talking out of my ass. I’ve tried to understand it.”

Beau Wollens was director of operations at HBA for two and a half years and left in 2015. I asked Wollens why, in his view, HBA had closed. “At the time, it seemed so complicated,” he said, “but it’s really simple. It was a bunch of inexperienced kids striking success against all odds and then dealing with nine-month lead times and manufacturing across the globe and department-store delivery schedules and also trying to navigate fame through that whole process.”

Another individual with close ties to the brand confirmed that account. “What happened was an absence of structure and an excess of idealism,” this person said. “Leilah is a creative person and so is Shayne, and she got swamped in the CEO role. All the shit was being delegated to her, and she was like, ‘I wanted to make films.’ ” Weinraub left to finish her 2018 documentary Shakedown, about an underground lesbian strip club in L.A.

Weinraub herself traces the problems to fractures within the thing that was vital to Hood’s creative energy: the collective. In the beginning, “I was advocating for a collective because I believed in collective ownership,” she told me over Zoom. “We were really experimental! Remember our shows and how long the credit sheet would be? It was really, like, We did this together.” Both Weinraub and Oliver spoke about a lack of communication. “By 2016, our success was growing,” Weinraub said, “but our relationships within the company were completely falling apart. There were constant arguments about money and credit.” I asked if she has regrets, given everything Hood By Air represented. “Yes, absolutely,” she said. “We all came from similar families. I wanted us to have stability. I wanted our shows to be a performance of chaos and not for us to live in that. So yes, I think it was a mistake not to resolve it. It was basically a tragedy and a missed opportunity.”

Wollens told me, “I think that everyone there was just trying to help and had some skills, but not all of the skills to effectively run a business that was doing millions of dollars in revenue almost overnight.” He added, “It would be silly to assign blame for something that was a complete creative project for ten years with your friends.”

The industry moves much faster now than it did five years ago, and looming over the new show is the question of whether Oliver can connect again with audiences. Many of the stores that carried Hood By Air — Barneys, Opening Ceremony, Colette — have closed. Streetwear and prep classics seem entrenched, limiting the space for risk-taking “concept” fashion. And not least, new stars have taken flight, like his friend Telfar.

Oliver, who is self-funding his new Shayne label from money made through collaborations with brands like Diesel, doesn’t seem concerned. The old HBA energy will still be there, he said, smiling. “The vibe is the vibe. I’m not getting all, like, Yohji. It’s not getting quiet.”

Certainly, those who know him well say not to underestimate him. Smith said it matters to Oliver to see “a ripple effect” from his work: “It’s the ego part, whether that’s a good thing or bad.” And Wollens said, “I feel that he does a great job of keeping his world interesting.” He added, “That feeling for what’s next — you just can’t teach that.”

Speaking of what’s next, I asked Oliver who he thought would replace Abloh at Vuitton. Our conversation had entered its third hour and was flowing freely. Later, though, his comments would strike me as telling, then oddly electrifying. He mentioned some names people were saying: Samuel Ross, Kerby Jean-Raymond, Martine Rose. Suddenly, he put in, “Listen, if Vuitton came around and knocked on the door, I would definitely do it.” He said of the brand, “It needs a double dose of chic. That’s for sure. Again, all the people we’ve mentioned are not fashion monsters. It takes a certain headspace. You can tell that the people we’ve mentioned have an attention to detail and that they’re speaking to a demographic — and that in itself is intriguing for their own brands. But you have to be a fashion beast and actually want to be chic. In menswear, that’s been missing for a very long time. What if you actually wanted a Vuitton suit?” Apropos of his own project — Shayne Oliver — he said, “I’m ready to make new shapes. I’m ready to have a conversation that no one is having. Not the ‘Black conversation,’ not the ‘streetwear conversation.’ ”

That’s all anyone in fashion ever wants — to change the conversation. One thing that the creativity of Demna at Balenciaga has made clear is that the most contemporary of visions can not only find a home in an established house but thrive — provided there’s a structure and like-minded executives. “I hope that Shayne surrounds himself with the right people that he trusts to see his vision through,” Wollens told me. “Because I know that if he can do that, then it’s going to be really good.” Oliver said that is also his hope: to find the right partner for his new brand. He brought it up several times. But for now, he has his mind on the creative work and, of course, the return to the stage. “I’m not scared, but it’s a weird feeling,” he said, inhaling. “Wow, I haven’t done this for a while. But I am super-positive about fashion.”

Want more stories like this one? Subscribe now to support our journalism and get unlimited access to our coverage. If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the February 14, 2022, issue of New York Magazine.