For roughly three-quarters of a century now, ever since the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, in 1945, coping with the fear of nuclear war has been a part of everyday life in America. Of course, it’s a fear that’s waxed and waned a bit — right after the end of World War II, there was even a brief period of optimism about the possibilities of nuclear technology — but over the decades, it’s become firmly embedded in the American psyche. Though nuclear weapons haven’t been used in warfare since the ’40s, we’ve remained collectively terrified of the possibility, in some cases with lasting psychological effects: During the Cold War, a raft of studies found that the pervasive fear of the time had a profound impact on how young people grew up.

One of those studies, published in 1986 in the journal Canadian Family Physician (and aptly titled “Psychological Effects of the Threat of Nuclear War”) found that those who were most affected by “threat of annihilation” were, perhaps unsurprisingly, some of the most vulnerable members of society: children, teenagers, unemployed people, and caretakers. Among children, anxiety was very high; teens, on the other hand, were more likely to respond with cynicism.

Very few of them, though, could bury their heads in the sand. Another study, published in the American Journal of Orthopsychiatry in 1982, found that the possibility of nuclear catastrophe was common knowledge among young people during the Cold War. Even without round-the-clock cable news coverage or a steady flow of information through platforms like Facebook and Twitter, kids of the time were readily exposed to (often horrifying) facts and speculation about nuclear tensions.

David Ropeik, a risk-management consultant who has written widely about fear and risk perception, recalls what it was like to grow up during a time often filled with such acute terror: “I remember going to bed one night during the [Cuban Missile] Crisis wondering whether I would feel the heat of the nuclear blast before it killed me, or if it would kill me so fast that I wouldn’t have to suffer,” he says. “That is how visceral and tangible, personal, real, and imminent, both psychologically and emotionally, the risk we were all feeling was.”

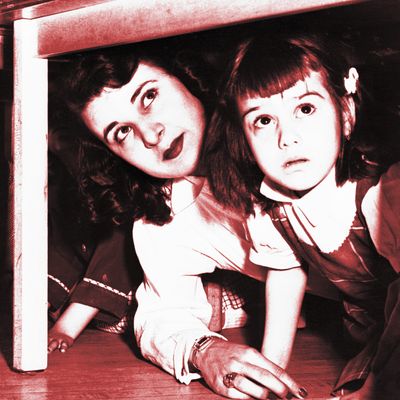

Ropeik says that even as a kid of only 10 or 11, he found it impossible to avoid news pertaining to the Crisis: “There were only three channels, and it was all they talked about,” he recalls. There was also the added seriousness of repeatedly seeing televised updates from the president himself. (Interestingly, though, the duck and cover exercises — common Cold War–era safety drills that took place in schools — didn’t stick with him as a fearful memory. “Those were fun,” he says.)

Ropeik’s father was a newsman, making him perhaps even more aware than the average kid, but in general, kids took their cues about how to react from the adults around them. Another 1982 study in the American Journal of Orthopsychiatry concluded that children’s observations about how adults coped with the threat of nuclear war had a significant effect on how trustworthy they perceived the adult world to be. It wasn’t an easy time to be a kid, but the Cold War wasn’t an easy time to be a parent, either.

Even now, on the other side of the Cold War, those effects can linger. According to Ropeik, people who have been exposed to high-level threats (or even non-weapon nuclear disasters like Chernobyl) tend to be more sensitive to new and similar threats as they emerge. Take, for example, the news about nuclear-weapons testing in North Korea. Those who have Cold War–era memories of nuclear fear, he explains, are more inclined to feel a sense of panic over each new update than those who came of age later.

Which isn’t to say that another particularly nuclear-sensitive generation won’t crop up in the future. Currently, the Doomsday Clock, which measures how close we are to a worldwide doomsday-level disaster (from nuclear war, climate change, or other threats) is positioned at two and a half minutes to midnight. And in 2010, Harvard University hosted an event titled “Nuclear Weapons, Primal Fears,” in which a panel of experts agreed that the fear of nuclear catastrophe is legitimate. The panelists advised the public to get involved with activism — boning up on nuclear issues, contacting elected officials, joining anti-nuclear groups — as a means of channeling that fear into something productive.

In the meantime, though, the last few decades have seen markedly fewer studies on how nuclear fears impact the psyche, even as these fears linger and morph with the ever-changing geopolitical landscape. Nuclear fears will exist to some degree as long as nuclear weapons exist — something that doesn’t seem likely to change anytime soon. The Cold War may be over, but there’s no doubt further psychological insight can be gleaned from this particular time in the nuclear era.