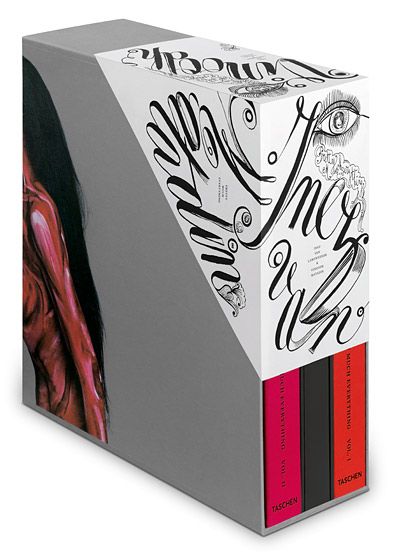

A photograph by Inez van Lamsweerde and Vinoodh Matadin is almost always instantly identifiable. Be it an image from the duo’s longstanding collaboration with Yves Saint Laurent or their beautiful nude-portraits series, the Dutch pair consistently inject their work with a slightly surreal, subversive twist. “There’s a duality and ambiguity in every image,” says Van Lamsweerde. “There’s always a dichotomy — whether it’s the tension between the beautiful and the grotesque, the spiritual and the mundane, high-fashion and low-fashion — there’s this in-between moment.” To commemorate over 25 years of being the industry’s most in-demand couple (who have a 9-year-old son, Charles), Taschen’s newly released book, Pretty Much Everything, contains, well, pretty much everything over the span of their career. We rang up Van Lamsweerde recently to discuss how their work has changed over the years, the importance of social media, and America’s irrational fear of nipples. See a preview of the book in the slideshow ahead.

What was the process behind selecting the images for Pretty Much Everything?

We started [the book] nine years ago and thought that we would do a chronological order of all of our years working together. Then we kind of felt that it wasn’t as alive as we imagined all of the images to be. It didn’t convey all the elements to our work — the fashion work, the portraiture work, the art work — as energetically and intuitively as the way we think about it. So we decided to forget chronological order, and really only work with pairing images that really connect to each other — [in the way that] we always felt that things relate, either on a formal or a very personal level. [This could be] in terms of inspiration, or maybe the person on the right-hand page is the friend of the person on the left-hand page; simple things like that. But every combination in that book has a reason.

The images were cohesive, despite having no real sense of order.

Yeah, that’s exactly what happened and why also it was so exciting for us to do it like this. It gave us a chance to look at all our work as one big body, as one big sentence. It’s great and very open-ended — that’s also why it took nine years, because we kept shooting and evolving and new things came up. It was too exciting to stop at a certain point — we just kept going. I think maybe even three days before the whole thing went to press, we were still changing images around.

But the book was originally planned to be in conjunction with your photo show at the Foam Gallery in Amsterdam back in 2010.

Yes, it was. It was supposed to be done by then, and obviously it wasn’t because we were still playing with it all. And the show consisted of 300 pieces, while the book has 666 images. So the show is now — it’s a traveling show—it’s an evolving thing, too, where we’ll add things or change things around.

Are there plans to bring the show to New York anytime soon?

This would be the dream. As of now, there’s nothing locked in. It’s going to other places in the world — it has been in São Paulo at the Biennial Pavilion. We’re working on [bringing it to] New York.

So, the book contains 666 images … coincidence?

I love that number. I like the heavy metal connotations. And at some point, we had to stop and say, “Okay, you cannot go bigger because then it would be a three-volume thing.” Essentially, it consists of two volumes. It’s one big book that is spliced in two — two people, two brains. And then in the middle of that, there’s the reader, which is a pocket book with all of the essays, fiction, and poetry that was based on our work.

In the introduction, writer Michael Bracewell links your work to the likes of Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Jean Genet. Are there any artists working today that you find particularly exciting?

I would say Cindy Sherman is one of my all-time heroes. David Lynch is a continuous source of inspiration. And there’s the Swiss painter Franz Gertsch — he does photorealistic paintings. His work is an unbelievable inspiration for us because what he does is, he takes photographs — he takes snapshots of, for instance, Patti Smith rehearsing in the seventies, and then paints them as big as a wall. They’re gigantic paintings that look like photographs. It’s this freezing of time. And his sense of color and texture is unbelievable.

Speaking of mixed media, you’ve made the jump to moving image recently.

I don’t want to say that the future for photography is film, but it could very well be. For us, it certainly is an incredibly exciting element that brings so many possibilities and ideas, like music, editing, special effects, illustrations, and animation. And it’s extremely fun — there’s so much more that you can say in a film.

In terms of casting, Daria Werbowy, Maggie Rizer, and Raquel Zimmermann are some of your most photographed subjects. How involved are you in the process?

Very, very much so. It’s very, very rare that the casting is done without our input. We always say, “The reason why we’re taking pictures is that we love people. We love being with people.” We always say that we can take an incredible photograph of basically anyone, but there are some amazing people around, like the girls you mentioned, who are continuously inspiring. And for us, that’s what it’s really about — the exchange with the person in front of us and bringing out the essence of someone’s look. It [requires] mutual inspiration, and there’s an element of trust when someone poses for you. Even if it’s their job, they have to be incredibly open and project what it is you’re trying to convey in that picture. It’s a delicate and beautiful thing, and we always feel very lucky.

That’s apparent when you look at your nude portraits of Carmen Kass, Shalom Harlow, and all the work you’ve done for V and Purple magazines. It seems like most people react very viscerally to the images, but also know there’s a cerebral aspect to them, as well.

Well, I think it’s exactly what you’re describing — whether consciously or subconsciously, we’re always looking for that tension. I think that’s when, for us, the photograph has succeeded. I think it’s rare, that mixture of feelings that comes from looking at the images. And again, like you’re saying, we’re always looking for a very aware image. There’s never that moment where we’re trying to shoot someone without them really knowing what’s going on. Everything is very open and direct. And that’s why you get the sense that the people are [being] themselves. They are aware that they’re photographed, and they’re photographed with as much dignity, grace, and respect as we could possibly imagine. So it’s about elevating every aspect of the person in front of us.

How do you create that tension?

It’s something that happens very intuitively. Sometimes it’s really in even a small hand movement or the way the body is positioned. Sometimes it’s the expression or it’s the fact that the hair is just maybe too much of one thing or the other. Again, what we play with a lot in our fashion work is the language of fashion, and for us that’s such an inspiration. It’s a universal code of fashion in which people are able to communicate without words. All of us know that a Rolex watch means something very different from an Hermès watch, for instance. There’s all these codes that have to do with status, with aspiration, with who you want to be, what music you listened to in your teenage years when you were forming your identity. All of those elements come into play. And it’s usually, for us — together with the editor, model, hair and makeup people — making this combination of elements talk through clothes, hair, and makeup. It’s that process in which we always try to find this duality aspect.

With your digitally manipulated work, how much of the final result of the image is from the actual photograph versus the altered parts?

We usually know beforehand if it’s a shoot where a lot of elements are going to be combined on a computer, like background or foreground. Then, knowing all that, we plan ahead and formulate it and shoot accordingly. But generally speaking, I think we alter very little in our images. We try to stay as true as we can to what actually happened on the day of the shoot and try to get everything as perfect as possible in the actual shot, and then it’s maybe just taking out a few elements that bring nothing extra to the photograph.

But then again, a lot of people ask us, “Oh, what do you think of all this over-retouching, and celebrities being skinnied up in the photograph, or have so much retouching you hardly recognize them?” Personally, I don’t really object to it; it’s just not something I’m into for our work. But I think in this day and age, people know more and more what the possibilities are with Photoshop, so these retouched images of celebrities become almost an avatar for that person. It’s their avatar — it’s their image image. And it doesn’t really matter whether they really look like that in real life. In my mind, it’s just another way of representing yourself. And, yeah, there are photographers that are really into that. But that’s not something that interests us, unless it’s a conceptual idea that has a clear motivation behind it that’s not just for beauty reasons.

When you think back to when you first started out in the eighties to where you are now, how has your work developed over the years?

When we were working on the book, we noticed that our inspirations and motivation are the same. There’s just so much more experience and confidence now that we are sort of more restrained. We have about 400 ideas continuously, and when we started out, we would try to put all those ideas in one photograph. But now it’s easier for us to say, “No, let’s save this idea for that,” and not try to cram them all in. I think our work has benefited from that. There’s definitely now a sense of like, “This is what I do. I know what I can and what I can’t.”

The field of fashion photography has long been dominated by men. In the early stages of your career, did you find it difficult to break through?

What I experienced in the beginning most was this lack of confidence in the technical side, being a woman. In the early days there was a lot of, “Well, she’s a woman, can she manage technically, does she know what light is about, cameras?” And all that sort of macho stuff. It took a while before all that went away, and now, usually it’s quite the opposite — people tend to really love the idea that there’s a man and a woman shooting at the same time, and it’s two visions on the same subject. And for me personally, being a woman, I want the girls that I photograph to look the way I would want to look. There’s so much mutual trust that way.

You both play an active role in tweeting and posting on your Tumblr, which is great for that lonely kid in Kansas who adores your work. How has social media affected the way you guys conduct your shoots?

I think it has freed us up so much. It is such an inspiration for us. Number one, it has made us look at photography very differently, because now anything can be an inspiration to us. I might see a stop sign in a field that looks incredible, so I take a picture of it, put it on Tumblr and communicate about it. It’s essentially like having your own magazine. I love the democratic sense of it; it’s immediate. Everybody now wants everything in real time. We also notice it now with clients that tell us, “Please don’t tweet on set.” Or “Please tweet when it’s out.” It definitely has a huge influence.

Going back to your work, specifically your nude portraits, what is your stance on porn, seeing as how that’s often America’s primary association with nudity?

Growing up in Amsterdam in the seventies, people would streak on the streets and [it was] such a sexually liberated country to grow up in. This whole idea of the American denial of the existence of nipples and everything else has, in part, given us inspiration for certain artworks that we’ve created. But at the same time, we generally feel it’s a shame that people deny themselves the beauty of the body. I think everything in the States is labeled porn very fast. The moment you see a nipple, it’s considered porn, and again, I feel it’s a shame because the human body is so beautiful and there’s so much tenderness and real-life feeling coming from it. We’re always thinking, “My god, look at the front pages of the newspaper.” There are the most horrible war scenes constantly on television and in the papers, and we always say, “It’s much more innocent to see a nipple than all this violence.” It’s hard, especially when you have a kid whose perception of the body is so beautiful and so innocent, to sort of taint it with this notion that it’s something that should be behind closed doors. That you should never see anyone naked is something that’s very foreign to us because of the way we grew up in Amsterdam.

You’re constantly traveling around the world for assignments — how do you juggle motherhood with your career?

Charles travels with us. He goes to school in New York City, but he has a teacher that travels with us. That balance has worked very well for him — to have the whole social aspect of learning in New York and then the one-on-one teaching when we’re away. And, in fact, he sees so much more of the world than we do. Usually when we’re shooting in Morocco, we’re on one location in the desert for five days, but he goes to all the markets or goes on a donkey up into the hills. He has more experiences than we do. So it’s made him look at the world not as a big place, but as a place you can have in the palm of your hand. It’s made him really flexible, and he has learned to really live in the moment and embrace everything that happens. He just takes it all in, wherever we are. It’s a wonderful life for him.

Sounds like it.

People on our team say, “When I come back to Earth in a new reincarnation, I want to be Charles Matadin.” That’s sweet.

What are your thoughts on the phenomenon of street-style photography? Do you think it’s a positive thing?

Yes, I do. I think it has changed the way people respond to fashion, especially with the availability of the fashion shows on the Internet. I think that people are generally more interested in knowing what their neighbor or best friend is wearing . Or, you know, let’s say a fashion editor they find inspiring. I think it’s actually shifted people’s attention away from what’s happening on the runway to what’s happening on the street. I think it makes everything much more democratic and much more related to real life. At the same time, I feel that, because of it, designers have to work so unbelievably hard these days. I don’t even understand how they manage to do that many collections and that many shows.

Yes, they have pre-fall and resort to worry about now, on top of their fall and spring collections.

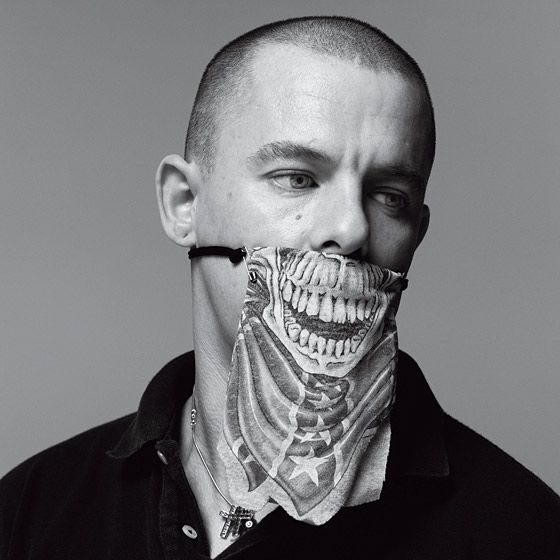

Oh my god, it never stops. And they’re the ones that have to have the original idea. They have to start from nowhere and bring it on the runway and I think that pressure is almost too much. The amount of work that’s now required of a designer is almost borderline what is humanly possible to still be inspired and creative.

Okay, lightning round: Who would you like to photograph that you haven’t already?

Prince.

What projects are you currently working on?

Many. But there’s another video project with Lady Gaga in the works, which is very exciting for us.

Guilty pleasure?

Chocolate.

Who takes longer to get ready in the morning?

[Laughs.] We’re kind of on equal sides there. Yeah. It’s kind of equal. Both of us take the same amount of time.

Finally, what advice would you give to aspiring fashion photographers?

Well, I always say study. Study, study, study as long as you can. Stay in school — you need that time to find your own inspirations and formulate your own style. And to build up the confidence to be able to handle the pressure of the reality of a fashion shoot, [which are often] twelve images a day.

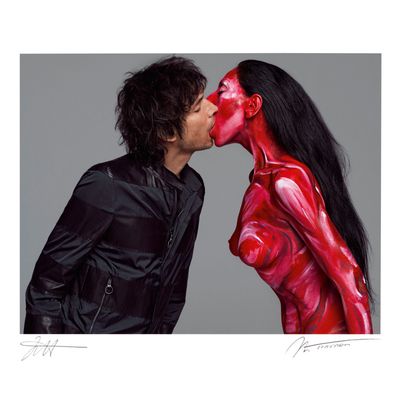

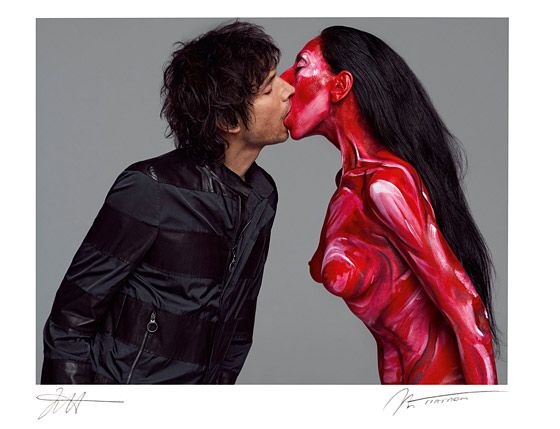

“Me Kissing Vinoodh (Eternally),” 2010.

“Lady Gaga – V Magazine,” 2011.

“Alexander McQueen,” 2004.

“The Widow (White),” 1997.

“The Forest – Andy,” 2005.