It’s 8:57 on Saturday night at Louis Vuitton in Beijing when a half-young couple pushes past the employee standing in the doorway. “They close at nine o’clock,” says the man, congratulating his date. They head directly for the wall of handbags. She is dewy and doe-eyed in an A-line dress and stilettos. He’s wearing the simple cotton shoes in vogue among government officials, a show of solidarity with the peasants who traditionally wear them.

“Which one do you want?”

She barely murmurs a response, instead motioning to the employees to take down the yellow, orange, and purple versions of the classic Alma model. “In shopping, you’ve got to buy things that are unique, cao,” he says, punctuating himself with a word that translates most literally as fuck but has various connotations depending on the tone. “Don’t buy the same as everyone else, cao.”

She settles on red, the same shade as the Young Pioneer scarf every student has to wear in grade school. He swipes 12,200 yuan, nearly $2,000. The whole process takes less than ten minutes. Moments later, they’re driving off in an Audi with People’s Armed Police license plates.

Gucci has three times as many stores in Beijing as in New York, and Louis Vuitton’s new Shanghai store has the floor space to rival its Champs-Élysées flagship. Chanel once did a China-inspired collection and put a Coco retrospective in the National Art Museum last fall, while Cartier had a show in the Forbidden City, Dior took over Beijing’s most prestigious contemporary-art museum, and Karl Lagerfeld held a Fendi fashion show atop the Great Wall. The average annual disposable income in urban China is $3,000. But China also has an estimated 600 billionaires and more than a million millionaires — in U.S. dollars. And non-millionaires are often as dedicated splurgers as they are savers. McKinsey & Co. has forecast that, by 2015, upper-middle-class Chinese consumers, with annual incomes from $15,000 to $30,000, will be driving almost a quarter of the nation’s luxury-good purchases, and a baker whose jumbo steamed buns I’m partial to just told me that he gave his wife a Céline purse for her birthday. (Its cost was a quarter of his monthly income.) Luxury brands are now looking to expand in cities that were previously considered backwaters, such as Kunming and Taiyuan. The Chinese spent an estimated $43 billion on luxury brands last year, according to Bain & Co. — most of which was spent in Hong Kong, Macao, and other global shopping destinations. That’s in part, of course, to avoid import taxes. (In Hong Kong, which doesn’t have taxes as onerous as China’s, Chinese mainlanders line up for hours to get inside stores, and tension over these luxury tourists has provoked protests by the locals.) But even when they’ve had to pay 40 percent more for an Armani bag in Beijing than they would have in Milan, they’ve paid it. As Europe slumps, the U.S. limps, and Chinese manufacturing slows, luxury consumerism here remains a growth industry.

In many ways, that consumerism is no different from consumerism anywhere: People want to wear nice clothing because it comforts and cossets, flaunts and shields. But in other ways, the country is a unique marketing opportunity. For one thing, gifts make up almost 25 percent of purchases, reports Bain & Co. Gifts for government officials, gifts for lovers, gifts for clients. That’s why wallets, charms, and handbags are such a big deal; they are easier to give than clothing. And who wouldn’t want to receive a Louis Vuitton $5,400 lantern charm made of red lacquer and yellow gold? Leather name-card holders are also very popular.

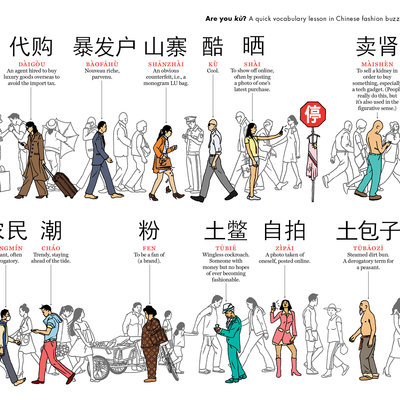

Another difference is that, in China, men are buying more of these goods than women, according to Bain & Co. The Los Angeles Times recently reported that “man bags” account for about 45 percent of the $1.2 billion in handbags sold in China, compared to just 7 percent in the U.S. In an economy and society so massively in flux as China’s are now, conspicuous consumption is necessary to attract clients, even friends. The buzzword on blogs is shài, to show off.

Who’s showing off the most? A snapshot of Chinese consumerism, fall 2012.

THE IMPORTANCE OF MISTRESSES

A handful of women in China are known for their tastemaking and spending. One who frequently graces the pages of Vogue China is Wan Baobao, granddaughter of Wan Li, who led the market reforms that brought prosperity to the countryside in the late seventies. Baobao attended Sarah Lawrence and now designs her own brand of jewelry. There’s also movie star Fan Bingbing, brand ambassador for Louis Vuitton, not to be confused with actress Li Bingbing, brand ambassador for Gucci. Then there’s Veronica Chou, who is less famous but far more sartorially influential. Her grandfather started what is now the largest knitwear supplier in the world. Her father bought Tommy Hilfiger and Michael Kors and helped turn them into international brands. And now she’s one of several tycoons frantically building stores in mainland China.

Chou and I meet for coffee in the cavernous lobby of a five-star hotel in outer Beijing. She’s dressed professionally in an off-white blouse with a tiny lion print, pants and pumps, and large diamond earrings. She’s heading China’s expansion of the Iconix brand family, which includes a dozen staples of the American department store, from London Fog to Rocawear. By the end of this year, with her Chinese retail partners, she will have introduced the Iconix stable into 700 stores in China. She flips through a booklet of brands she’s working with, making it seem as easy as a Monopoly game. Just a matter of licensing.

“A lot of rich guys don’t know how to dress well,” explains Chou. “So they just buy the obvious, the big brands. But their mistresses are more fashionable. Mistresses are driving the designer brands in some ways.” Being a mistress in China is not at all like carrying on a clandestine affair with a married man in America. Their role is social as well as private — and that requires dressing well and working out, and possibly advising men on how to do the same. It’s often their job to write the shopping lists.

MEN SHOPPING FOR SHOES — AND WOMEN

The businessman looking to flirt is at the Costa Coffee shop at Beijing’s Shin Kong Place, one of the highest-grossing malls in China. He flashes his diamond-rimmed Patek Philippe watch while accusing the barista of watering down his latte. He says his name is Shijun, and no more than half an hour goes by before he makes his first (quasi-contractual) bid for my affections: “How about 40,000 yuan per month?” (That’s $6,270 plus free rent in a special apartment.) He speaks with a heavy Sichuanese accent, China’s version of a southern drawl. He made his fortune in office-building and housing development in China’s western frontier, the Qinghai and Xinjiang provinces, where the central government is “encouraging” Han people to settle. Shijun’s wife is in Italy, or maybe Switzerland, and his daughter is in high school in the United States; he doesn’t know where exactly. He doesn’t have much else to do today besides cruise for new clothes and women.

“I like luxury goods; I love to consume,” he says. “I have money; I gotta spend it.” He is wearing Ferragamo shoes, an Armani polo, and Kiton pants. The wallet is from Bottega Veneta, the socks from Prada. The underwear? He says I have to accompany him to the hot springs to find out, but he assures me that they cost more than 800 yuan, or $125.

We head to Kiton to pick up a pair of jeans he just had shortened. Making an appointment for a suit measurement, the employee tells him, “We’re setting this up ahead of time with the tailor; you have to be here. You can’t reschedule with these Italian brands.” Shijun nods eagerly. But he still needs shoes to go with the new jeans. So we get in his Porsche Cayenne Turbo SUV to drive a mile to a mall nearby. First stop: John Lobb, to try on several pairs of driving shoes, 11,280 yuan each. Second stop: Berluti. There he swipes his card for a pair of blue suede loafers that seem like a comparative bargain at 7,200 yuan. “We should go into business together,” he says. “We could make a fortune — and a baby.” Third stop: hotel lobby for tea with his coal-mining friend, who he assures me has a net worth of more than 500 million yuan. The man is a generation older than Shijun and either dislikes the new loafers or the attitude behind them. He turns away when Shijun asks excitedly, “What d’ya think of my new shoes?”

THE NECESSITY OF VANITY

Tiffany Zhang, 30, is married to a billionaire property developer, the chairman of Yintai Group. I meet her in the basement of the second tallest building in Beijing, the Yintai Centre, in an English tea shop that sells Aynsley bone china at 2,380 yuan, or $370, per teacup. Zhang is also from Sichuan but long ago lost the drawl. She flies back and forth for the shows in Paris and Milan, and is considering buying one of the more down-and-out European luxury houses. Harking back to her days as a TV actress, she has camera-ready eyelashes and wears swirly dark contact lenses that make her irises distractingly enormous. She carries a braided Balenciaga bag; it’s not one of the imitations sold on the subway steps outside. Counterfeits may be thriving in China, stitched together by children in illegal factories run by mobsters. But as soon as people can afford to, they often buy the real thing.

“We don’t talk about the Mafia,” says her spokeswoman. “The consumers are cheating themselves. It is pitiful,” Zhang adds. “On an Hermès bag, every detail is perfect from every angle. However you look at it, it’s perfect.”

For Zhang, the ability to buy something special, and genuine, is a sign of a healthy society. “Everyone needs goals, something to pursue in life. Aside from love and taking care of family, everyone just wants to improve their quality of life. What else is there? Even a taxi driver wants an Hermès belt, an LV wallet.

“It’s not about vanity. It’s about the value of your existence, your worth in this society. Sometimes people say Chinese people buy out of vanity. I say vanity is a necessity. It proves your self-worth; you’ve worked hard to earn it, and this is what you’ve earned.”

A TRIP TO THE MALL

The Young Lovers

Ed Hardy, Chou told me, is one of her fastest-growing brands in China. By the end of the year it will have debuted in 30 malls. It’s also four times more expensive than in America: 1,980 yuan, or $310, for a rhinestone-studded “love dies hard” T-shirt. In a welcome alignment with Chinese tastes, there’s also a T-shirt collection featuring a dragon, a tiger, and other signs of the zodiac. (Chou notes that softer colors tend to be quite popular here, too: pink and baby blue. And, as is the case in Japan, cute sells. Women in their thirties — and some men, too — wear cartoon characters on their shirts. “Cute is better than sexy,” she says.)

Dong Le, 23, who drove in from Hebei province for the weekend with his girlfriend, is the son of a housing developer. “I don’t work; I’m just at home,” he says. This is their first time in Ed Hardy. “These sweats are great,” she says. It’s clear she wants him to try on a matching pair, and he finally does. “Okay, I’ll try the pants,” he declares, standing up from a pink cowhide bench.

Moments later, she is wrapping her arms around his waist. They study themselves in the mirror for half an hour, debating whether to both get the same color. “Do you like the green on me?” she asks. “I like the gray,” he says. “That way we match.” He tries a black tiger-embroidered trucker hat. “It’s fashionable: tigers and diamonds.” An hour later, he swipes $1,100 before they head back to Hebei.

Snobs in Ascendance

As new millionaires and white-collar workers start wearing genuine designer logos, they raise the bar for those who want to remain among the fashion elite. So the creative quest continues for other, subtler ways to spend big. “People are more attracted to the lifestyle than the label now. Before, they wanted people to know that they could afford it, so they would buy something with a big label,” says Francis Wong, the creative director of Stylesight, a forecasting and advisory firm. “But now they want people to know, ‘I have taste.’ ”

In July, responding to online criticism of officials photographed wearing bling, a new law went into effect to encourage government officials to be more discreet with their designer outfits. Zhang said she expects this to have less of an impact on overall sales than on what exactly will sell.

“People are shying away from anything conspicuous,” says Jeffrey Ying, an American-born freelance stylist. “The wealthy are starting to move away from that preoccupation with status symbols. [Some brands] are kind of gauche. They’re starting to consider heritage and quality. So it’s a form of inconspicuous consumption that people in their social circles will recognize versus people on the street.”

Other luxury brands fit right into this rising consumer consciousness. One Friday night, a Gucci store has imported blond and brunette cobblers to sew and polish shoes at a cocktail party. One of them is explaining the no-socks-with-loafers trend, with help from a translator: “See, the seams are around the outside, so there’s nothing poking into your feet, because your feet are very sensitive.”

“We all used to wear plastic slippers,” a young man named Wu Ruiqi says while sipping Champagne. “There wasn’t fashion before. Everyone wore the same thing. Now there are two kinds of shoppers: fashion-forward, and clichéd customers who all buy whatever brand just for the logo, like a swarm of bees.”

The Window Shoppers

Luodan, 9, visiting from Xi’an, is vamping in front of the Chanel and Dior billboards as her parents take photographs. “It’s very pretty, but we don’t understand these English names,” says her father. “It’s too expensive for us,” says her mother. The father shrinks away. “We can’t afford it.”

Some nearby storefronts have English names — White Collar, Elegant Prosper — but are clearly not imports. “A friend of mine tried to start a sportswear line with a Chinese name,” says Chou. “The department stores made him change it.” The Wall Street Journal recently noted a few of the more mockable brands with Western names: “b + ab,” with its “gotta pick my precious love collection,” Best Raiment of Jauntiness, and a sunglasses line named Helen Keller. The truth is that some Chinese people are still loath to buy clothes with a Chinese brand name. It’s not cool.

The Woman Who Understands Why Other Women Become Mistresses

At Chanel, 25-year-old Qi went in to exchange a skirt and ended up buying a pair of monogrammed stud earrings. She invites me to chat in a café across from an enormous Emporio Armani. Originally from northeastern China, she opened a nail salon in Beijing a few years ago, and now spends 60 to 70 percent of her income on designer clothes and bags.

“I don’t have any other hobbies,” she says. “My only hobby is shopping.” She is wearing a white-lace dress and a diamond Dior monogram necklace, the same one that a girl who walked out of Chanel a few minutes before her was wearing. “Beijing girls, they all buy the same luxury items,” she says. “It doesn’t matter if it takes a month’s worth of salary. Chinese people are blind followers. Some people say they hate rich people, but it’s just sour grapes. If they had money they would buy it too.

“Fashion ruins some people and saves others. A friend told me that seeing all the things at this mall inspired him to work harder; it gave him something to work for. Otherwise what is the point in living? But a lot of women, for a bag or a watch, will do bad things, they will sell themselves. I have a friend,” she says, “who will do it, but not for just 10,000 — only for at least 100,000 yuan. I’ve never thought this was particularly wrong. There are many different ways to make money.”

She quotes Deng Xiaoping, who launched China’s capitalist reforms. “ ‘It doesn’t matter if the cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice.’ Even these girls with white-collar jobs, with respectable jobs, they would sleep for money, too. There is some number that would get you into bed.” I realize she’s brought me back to the same Costa Coffee where I met the Sichuanese developer.

Then she says, with a laugh, “If there were half as many Chinese people in the world, these brands would go bankrupt.”

This story appeared in the August 20, 2012 issue of New York Magazine.