Even in the dead center of a Paris winter, when the sun hasn’t been out for hours, if not days, Olivier Zahm’s eyes are all but invisible beneath the Coke-bottle-thick prescription amber lenses of his Ray-Ban aviators. Seeing him in public without them would be like spotting a unicorn in the Jardin du Luxembourg.

“I like the look,” he explains. “I also have a problem with migraines. I’m sensitive to the light. But the world is much more beautiful in color.”

Zahm is sitting at his desk in his office on Rue Thérèse, a few blocks from the Palais-Royal and just down the street from the apartment he shares with his girlfriend, designer Natacha Ramsay-Levi, and their 6-week-old son, Balthus Billy. “I’m not a baby fan,” he says, “but when you have one, it is very joyful. I change diapers. It takes two minutes.” From a desk drawer he pulls out a rainbow assortment of other glasses. He removes the amber ones, and his eyes are momentarily visible. He squints. “Do you like purple?” he asks, quickly slipping on a violet pair. “It helps. You have to protect yourself from the ugliness and vulgarity all around us.”

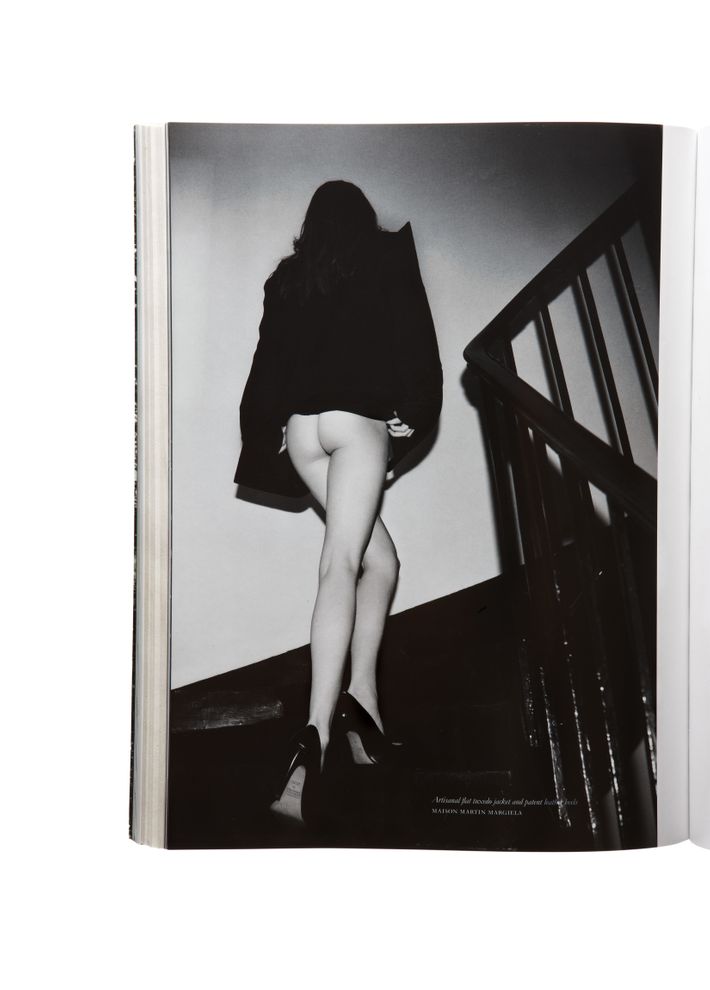

At 49, Zahm, with his sunglasses, bed-head, and motorcycle jacket (today, a Rick Owens), is a glittery, grungy subspecies of celebrity editor. And unlike his more famous peers—Anna Wintour, Joe Zee, Anna Dello Russo, Grace Coddington—he has achieved this status despite never having had a reality show, run a Condé Nast title, or trotted around with a pineapple on his head, as Dello Russo is wont to do. As editor and creative director of Purple Fashion magazine, a 75,000 circulation biannual publication (only available on import for $40 an issue in the U.S. at specialty newsstands), he has established himself as one of fashion’s more influential tastemakers by relentlessly promoting sex in fashion, and fashion as sex. If many women’s fashion magazines almost seem to decouple sex from libido, Zahm can’t stop thinking of ways to fuse the two.

“Ninety percent of the attraction of women is style,” he says. “Old or young, if she has a good sense of fashion, I am in love with her. If she has bad style and a beautiful body, I run away. I don’t give a shit about beautiful style on a man. Men should keep a distance from fashion to find their own uniform,” just the way he did.

But women—they are the reason he got into fashion in the first place. “People see me as a womanizer, but that’s not the case. It’s just hard for me to resist the charm of a woman. I love every aspect of women, even the negative aspects when they get scary or crazy or super-emotional—I think it’s beautiful.”

“It’s not only that he’s straight,” says Masha Orlov, who has styled for Purple since 2001. “Jefferson Hack”—the father of Kate Moss’s child—“has a very sexual quality to him, but it doesn’t resonate in [Hack’s magazine] Dazed & Confused as much. Olivier loves women in general, and there is nothing sexist about it but sexual.

“Look at his new photographer-of-the-moment, Sandy Kim,” Orlov continues. “She’s super-voyeuristic. She shows you her period blood on her panties!”

Zahm would like to show a lot more than that, but “we have problems with cocks,” he says. “It is difficult to show cocks in a magazine without being pushed in the porn section or stopped at Customs. Man cocks, especially if they’re erections, they’re not allowed. Tits are okay, but a problem on the cover.” Zahm sidestepped this on the twentieth-anniversary issue last fall—a removable “1992” sticker served as the model’s tube top and went well with her Comme des Garçons trousers. Of course balancing out the shenanigans and lux fashion are extended interviews (often conducted by Zahm) with artists, musicians, and filmmakers such as David Lynch and Kenneth Anger.

There is a scratching sound, and Zahm points with his lit cigarette like it’s a ruler: “That’s cat peeing,” he says, always speaking in a slow, measured tone. “She is so serious when she pees.” Next to his chair is a canopied litter box with a gray cat’s head sticking out, sphinxlike. Yoko was named after the twin sister of his ex-girlfriend (and mother of his 8-year-old daughter, Asia) Anna Dubosc. “They live here,” Zahm says of Yoko and the other feline, Miko. “They couldn’t adapt to my apartment. They need the constant life of the magazine.”

This is the three-room headquarters of Purple Institute, the umbrella company that includes the flagship magazine and Zahm’s other endeavors—he has art-directed campaigns for brands like Yves Saint Laurent and produced magazines for Chanel and Printemps. This season he shot the campaigns for Agent Provocateur and Hogan Rebel.

The purpose of Purple Institute’s more commercial activities is to guarantee the independence of the magazine, which doesn’t lose money but doesn’t really make any either. Among Purple’s business challenges: Zahm sees every facet of the magazine as part of the whole and turns down ads if they are ugly. And while Purple’s website enjoys 300,000 unique visitors per month, those readers won’t be seeing pop-up boxes anytime soon.

“The site has become a reverential place,” says Zahm. “I don’t want advertising to destroy the aesthetic. How do you combine the aesthetic with advertising? I don’t know. Content is my main concern. I will make money one day.”

On the days I visited Purple Institute, the small staff was all female. “Working with Olivier is seeing his vision through,” says Caroline Gaimari, a brassy Boston native who is the magazine’s executive editor and fashion director as well as the grounded yin to Zahm’s every flighty creative wandering. “He knows what he wants, and you have to make it happen. ‘Okay, you want to shoot a girl in a church with a donkey? I can make that happen.’ I literally did make that happen two weeks ago. If he wants a donkey, you are getting a donkey.”

Zahm proudly micromanages every aspect of the magazine, including writing many of the articles and styling and photographing shoots. “I can give you the name of the glue I use to fix the pages,” he says. “I know every technical side of it.”

“People don’t get him,” continues Gaimari, who has been with Purple since 2006. “No one has written about how smart he is. I’m with him all the time. He’s at the office until four in the morning. There is no crazy orgy here; it’s him and the art team, and he has a vegetarian dinner at the Thai restaurant down the street. He likes to think he’s vegan.” She’s a little protective of her boss and a little weary of having his playboy persona overshadow their work.

That was the case in 2010, when there was much interest in Zahm’s risqué blog posts in the “Purple Diary” section of the website following a temporary breakup with Ramsay-Levi, which graphically documented his sorrow and the drowning thereof with other women. He wrote: “To all the anonymous friends who follow my life on the Purple Diary, I have to tell you that I’m in a lot of pain. Natacha Ramsay dumped me on Sunday. She ran away with her lover (with whom she has had a long romance that I was aware of and accepted) for a summer of love. She called me to tell me that she loves him, that we are finished. I asked her to come back two times and she said no two times. As you know if you follow the Purple Diary I try to create and promote an alternative love lifestyle (that I used to call in French La Communauté des Amants). Natacha’s decision to leave me so brutally and painfully will certainly be seen by conservative people as a clear feminine revenge against the lifestyle Natacha and I used to share, and think that I’m a dreamer. Right now I’m just a mess. But I will hopefully recover soon and offer you some more pictures of love and sex.”

The “Purple Diary” has chilled out a lot and mostly documents, amid Zahm’s party-hopping and gallery-crawling, his clear devotion to Ramsay-Levi, who is very much his muse. “I still maintain a personal approach to the diary, but less sexual,” Zahm explains. “At the beginning, when it was new, people were excited to be free and be a little bit exhibitionist. Now they see the problems. I have a friend naked on ‘Purple Diary’ be fired from the gallery she was working from in America. And even in France, Natacha, when she is still working at Balenciaga”—Ramsay-Levi has long served as designer Nicolas Ghesquière’s lieutenant, first at Balenciaga, now at his mystery next endeavor—“she had some problem with some picture where she seemed to be too naked.”

Zahm’s love of magazines began when he was a teenager in the Paris suburbs. “We used to steal porn magazines in the bookstores and shops and look at them during school,” he says. “It was fun and secret. This is where my obsession for magazines comes from. Magazines used to reveal and give us access to sex, fashion, and art. TV never did that, and books are mostly academic. Magazines were a symbol of freedom.”

His parents were both university professors; his father taught philosophy and his mother natural history. Until he was 10, the family lived on the campus at the Cité Universitaire. “I am a child of the ’68 revolution,” Zahm says. “It was a place with a lot of political and sexual agitation.”

He wanted to be a director but didn’t get into film school. So he immersed himself in the then-burgeoning Paris nightclub scene of the eighties and studied philosophy and literature at the Sorbonne. He became an art critic and journalist, writing for Artforum and Le Figaro, and drifted around Europe going to art fairs. When he needed to make some money he’d do a copywriting gig for advertising.

Purple was founded with Elein Fleiss in 1992 (they dated for a time, and in 2004 she left the magazine to Zahm). In its first incarnation, the magazine focused as much on art, fiction, and poetry as on fashion and photography. Olivier’s sister, Emmanuelle, used to help out with the magazine. When she was 20, she took her own life with an overdose of pills.

“She looked like my daughter,” Zahm says. “My sister was a beautiful girl, very open. She wanted so much from life, but she was living in a dream world. She couldn’t adapt. She couldn’t conform to the system. She couldn’t work. She was always suffering. She was trying to kill herself regularly since she was a teenager. She left home when she was young and led a very adventurous life, and it was difficult to help her and I tried.” Zahm’s brother is an engineer. Olivier sees himself as the middle child taking the middle path between traditionalism and excess.

For a modern magazine, Purple is not in hock to fame. Models often get the cover (which has somehow become a rarity for fashion magazines), and Zahm mostly passes over the lower-culture pop star or movie starlet of the moment. There was the Lindsay Lohan issue, but that was at the height of the Ungaro scandal (when Lohan was serving as artistic adviser to the brand) and was something of a middle finger to the fashion industry. The celebrities Zahm mostly prefers are people like Chan Marshall (singer Cat Power) or Chloë Sevigny, who’s been a friend of Zahm’s since 2001, when she was in Paris filming the movie Demonlover. “He took care of me,” Sevigny says. “He was such a good friend and would take me out to Café de Flore and drive me around on his motorcycle. He was more bookish and intellectual-leaning before he was such a star vis-à-vis the Internet, but he has remained true to himself. He was a little heavier before. He still had the aviators, and a lot of cigars were happening. He always had a cigar. But he still had great style. There was less tight jeans and leather jacket and more zhlub.”

She continues, “I’ve been in almost every issue. If I’m not, it’s because I’m not around. I like being around him. He makes you feel warm and is flattering and showers you with adoration. And he has very good taste. The magazine has changed since the early days. It was more arty and less sex-obsessed, and I miss a bit of that.”

Paris men’s Fashion Week has just started, and Zahm is in the backseat of a taxi navigating the roundabout at Place de la Concorde, the tacky Ferris wheel clashing with the obelisk. He is the kind of passenger who tells the driver the exact route to take. He’s used to driving—he has five motorcycles and a Vespa—but it’s a cold winter for Paris.

“I have an old Triumph,” he says. “You know when you have something in your mind and you want it? I got it the day I got my daughter. I was at the clinic waiting for the baby to happen, and I sneak out and came back with this powerful bike.”

Today’s motorcycle jacket is a suede shearling BLK DNM, and he has on his favorite pair of custom YSL boots and a gray hoodie with a cartoon of a guy puking. On his army-surplus camera bag is a crocodile luggage tag with OZ embossed in gold. We pull up to the Grand Palais for the Louis Vuitton show. Inside, he sits in the front row next to his friend and Purple cover alum Andre Saraiva, the graffiti artist turned Le Baron nightclub owner. “People portray Olivier as a big caricature,” Saraiva says, “ ‘the French lover.’ He likes to play with that, but he is much more profound.”

The Louis Vuitton show begins, a to-the-manner-born Sherpa fantasy, some models wearing monogrammed trunks strapped to their backs. Zahm photographs the show, often holding the camera by the floor or at some odd angle to shoot a detail of a garment, or stretching out his hand for a close-up of a model’s face. He leaves his glasses on, so the whole parade must seem a cavalcade of different shades of brown. “It helps a lot,” he explains. “The contrasts are more beautiful.” (Rizzoli is set to publish a book of Zahm’s photographs later this year.) After the finale, he goes backstage to congratulate the designer, Kim Jones. En route he sees Kanye West and says hello.

Zahm and Saraiva rush down the back stairs to Saraiva’s hired car to go have a coffee near the Purple Institute, but shortly after sitting down at the café, Zahm receives a phone call from Ramsay-Levi. It’s her birthday, and that night they’re having a family dinner. “The baby is freaking out, and she doesn’t know what I can do but she needs my help,” he explains, but first we must race across the street to the Institute to drop off the memory card of the Vuitton pictures. Zahm takes his daily photos very seriously, trying to get them on the site as quickly as possible. (“I’m like Warhol. He always had his camera.”) So he’s a little agitated when the elevator arrives and two old ladies are about to enter after us. Old ladies in Paris really dress like old ladies: fur coats, hats, canes, everything. “La prochaine! La prochaine!” (“The next! The next!”) he yells and shuts the door in their faces so we can ascend. He then realizes what he’s done and covers his face and laughs hysterically.

The next day, after the Krisvanassche show in the basement of the Palais de Tokyo, Zahm stops in front of the restrooms and motions at the symbols representing male and female. “I’m from another kind of gender called the artist,” he says. “Artists have no gender. They have all kind of sexuality, and they can morph into all kinds of body. They transform their body. They transform their mind. They are not man or woman. It’s another kind of category, it’s another kind of human. This category needs a special bathroom.”

As he walks to the exit he says, “I don’t conform with the way men interact with women. I have much more freedom than any man. It’s not just sexually oriented. The art community in a very broad sense …” and trails off.

Outside, snow is falling. “Artists, we are a species in danger,” Zahm says. “The true artists, we are overexposed. It’s why we have to protect ourselves. I am part of the problem! I am overexposing people and myself.” He squats down and shoots the fine powder settling on a marble balustrade. “I am constantly photographing,” he says. “I’m the opposite of a dandy. The dandy wants to keep for himself and have the most precious, rare, refined environment and protect himself with objects and his aesthetical world. I want to share it. I want people to understand.” At that moment a fashion editor Zahm knows passes by. She’s gorgeous and looks like an ex-model. They say hello before she’s off to hail a taxi.

“I try to fuck her seven times and I’ve never been able to,” he tells me. “It’s impossible.”

*This article originally appeared in the February 18, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.