The corporate headquarters of Abercrombie & Fitch, one of the largest apparel retailers in the world, spills across 500 acres of dense Ohio woodland, about fifteen miles from downtown Columbus. From the outside, the central office cluster resembles an Adirondack lodge as envisioned by a Brutalist—all hard lines and weather-beaten wood. Meals are served in a barn finished in rusted steel, and in the summer, companywide meetings are held in an exposed-concrete courtyard in front of a large fireplace.

Officially, the complex is the work of Ross Anderson of the New York firm Anderson Architects, but it clearly bears the fingerprints of Mike Jeffries, Abercrombie’s famously autocratic CEO. Jeffries, Anderson has said, “wanted to make sure the architecture and the brand both spoke in the same voice. They share the same DNA. Each reinforces the other.” To enter Abercrombie headquarters is to travel back in time to the world portrayed in the iconic catalogues of the late nineties—everyone is young, good-looking, and, despite the harsh Ohio winters, exceptionally tan. A miasma of Fierce cologne hangs in the air, and pulsating pop echoes through the corridors.

Jeffries, who at 69 years old still has the blond hair of an Abercrombie model—“Dude, I’m not an old fart,” he has said of the dye job—works on the second floor in an airy, sun-splashed conference room. He typically receives guests in his standard uniform: an Abercrombie polo shirt, artfully distressed jeans, and a pair of old flip-flops.

From 1992, when he was hired at Abercrombie, to the early aughts, Jeffries presided over one of the more impressive runs in the history of modern American retail. And he did it by turning an all-but-moribund clothing brand, best known as a fusty safari outfitter, into a multibillion-dollar behemoth with more than a thousand storefronts and a style that competitors were tripping over one another to imitate. Unlike his peers, who tended to view the youth market with clinical detachment, Jeffries had a Peter Pan–like ability to commune with the whims of the average American teen. As a former colleague once said, ideally, Jeffries “would like to be a guy with a young body in California.” He was able to predict what his customers desired because that’s what he desired too.

But by the early aughts, Jeffries was eager to expand the company, and that spring, he summoned a group of executives to his office to discuss the creation of a new line of apparel to be developed under the code name “Concept Four.” At the time, Abercrombie comprised three separate brands. Abercrombie Kids was for grade-schoolers; Hollister, a SoCal-inspired line launched in 2000, was for young teenagers; and

Abercrombie & Fitch, with its prep-meets-vintage aesthetic, was for high-school and college kids.

Concept Four, Jeffries announced, would target the professional crowd that had aged out of the core Abercrombie brand. It would still be recognizably Abercrombie—jeans, button-ups, polos—but slightly more muted: no shorts with racy language scrawled across the rear. In order to help implement his vision, he turned to an executive named Alisa Durando, who had spent several years at Abercrombie and was close enough to Jeffries that she was known around the office as “Mike’s pet.”

At least once a week, Durando’s team carted sketches and samples to Jeffries for inspection. Jeffries, typically coming off his regular morning workout at the campus gym, would be perched at the head of the table, flip-flops prominently visible, the sleeves of his polo shirt straining at his biceps. His critiques were precise; very little escaped his notice, including the placement of buttons and logos. As one Abercrombie designer recalls, Jeffries “saw everything. It was this sort of maniacal passion.”

Concept Four launched in 2004 as Ruehl No. 925, complete with a fictional backstory, involving a nineteenth-century Greenwich Village merchant, concocted by the marketing department. Initially, Jeffries was optimistic, and he spoke publicly of Ruehl as embodying “the fantasy of college kids of America moving from Indiana to the big city.” He invested heavily in an expensive ad campaign featuring black-and-white close-ups of lower-Manhattan brownstones—a self-consciously classier approach than the nude black-and-white images that graced Abercrombie storefronts and shopping bags. And in order to enforce the luxury nature of the brand, he stipulated that apparel prices should be 25 to 35 percent higher than they were at Abercrombie stores.

But Jeffries badly mistimed his entry into the market. Already, online sales were generating an ever-growing pile of revenue for the apparel industry, and fast-fashion retailers such as H&M were churning out low-price approximations of high-end items. Consumers failed to see the appeal of a line that trafficked in the same basic style as Abercrombie, especially when it was prohibitively expensive. In 2009, after spending untold millions, Abercrombie closed all 29 Ruehl storefronts nationwide. “He has a tough time moving past that classic American aesthetic of jeans and polo shirts,” a former Ruehl designer told me. “And when you’ve got an increasingly globalized, educated audience, that’s obviously going to be a serious problem.”

For Abercrombie, the collapse of Ruehl presaged a larger decline in sales and stature that persists to this day. Jeffries has been quick to argue that the problems facing the company are the same ones facing the industry as a whole, which is true: Teen spending is at perilously low levels across the board, and arch-competitors American Eagle Outfitters and Aéropostale are feeling the pinch, too.

But Abercrombie’s predicament, perhaps because of the cultural clout it once wielded, feels especially acute. “The sexy collegiate image fit into the age of Gossip Girl and 90210,” says retail analyst Wendy Liebmann, “but now it feels like it’s grounded in an era that’s at least ten years old. I don’t think shoppers in the U.S. and Canada have totally walked away. But, as a whole, I think shoppers have moved on.”

Last year, shortly after Abercombie announced a $15.6 million quarterly loss, Engaged Capital, a California company that holds about 400,000 shares of Abercrombie stock, wrote an open letter to the Abercrombie board demanding Jeffries’s ouster. In the letter, chief investment officer Glenn Welling wrote, “While losing Mr. Jeffries’ leadership may have been negatively perceived in the past, it should now be abundantly clear that a transition in leadership is not just needed, but absolutely required, to restore investor confidence in the Company’s future.”

Initially, the board, thumbing its nose at activists, said that it would extend Jeffries’s contract, which was set to expire this month, for another full year. His $1.5 million base salary remained intact. Then last month Abercrombie stripped Jeffries of his role as chairman of the board and brought in three new board members, including Arthur Martinez, the former CEO of Sears, as chairman.

“The board was woefully inadequate,” says Brian Sozzi, the head of Belus Capital Advisors. “It was just Columbus businessmen”—businessmen generally seen as not having the acumen or will to push back against Jeffries. “The takeaway here is that they’re finally getting retailing experts in there. It’s long overdue.”

Although Jeffries remains CEO, his position is greatly diminished. It’s a startling fall for a man many believed would remain in full control of Abercrombie for years to come. “You have to admire Jeffries for taking what was essentially an irrelevant brand and making it elite and cool, for making it a destination,” says Erik Gordon, an assistant professor at the University of Michigan’s business school who has studied Abercrombie extensively. “But if our hero has a fatal flaw, it’s that the world changed and he hasn’t.”

Mike Jeffries grew up in Los Angeles and is the product of what he has described as a “very classic American youth,” down to the Levi’s 501 jeans. From a young age he gravitated to retail, and he worked alongside his father in a chain of family-owned party-supply stores. “I would always say to my parents, ‘We need another store. We need another!’ ” Jeffries told Salon in 2006. “I always wanted to expand and get bigger, and I would get off on saying, ‘Why do we do the fixtures like this? Why don’t we do it another way?’ That totally turned me on.”

In the early sixties, Jeffries enrolled at Claremont McKenna College, where he studied economics, and after graduation he moved to New York to attend the M.B.A. program at Columbia. His first real job was at Abraham & Straus, a department store eventually acquired by Macy’s. There he earned a reputation as a hardworking if authoritarian manager with little interest in team-building. “A gifted guy who does it himself is different from a gifted guy who helps people help him do it,” Alan Gilman, the former chairman of Abraham & Straus, has said. (Abercrombie representatives declined to make Jeffries available for interviews.)

Later, Jeffries moved to the clothier Paul Harris to work in merchandising. He seemed no more connected to his new co-workers than he had at Abraham & Straus. “He kind of looked down on all the people around,” a Paul Harris colleague later told Businessweek. “He looked like he was listening to you, but I don’t think he ever was.” He was perpetually clad in a double-breasted navy blazer and dilapidated loafers—a far cry from the youthful style he favors today.

In 1984, Jeffries opened Alcott & Andrews, an upscale women’s clothing retailer. He bragged that his ideal clientele was “active, involved, successful, and affluent.” (The name was a nod to Jeffries’s son, Andrew, and Louisa May Alcott, the favorite author of Jeffries’s business partner Coleen Brady, who passed away a few years later.) But Jeffries had spent too lavishly on real estate, and in 1989, besieged by creditors and teetering under $36.5 million in debt, Alcott & Andrews filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. In its obituary, the New York Times prophetically noted that the store had offered “too little variety in its merchandise.”

In 1992, L Brands (then known as the Limited Inc.), an Ohio conglomerate credited with turning around Victoria’s Secret, hired Jeffries to help make over another ailing property: Abercrombie & Fitch. Founded a century earlier by the civil engineer and adventurer David T. Abercrombie, the company had originally trafficked in the same hardware Abercrombie had found useful in the field—compasses, canoes, fly reels.

Amelia Earhart was wearing a suede Abercrombie jacket when she flew across the Atlantic in 1932; Abercrombie outfitted Teddy Roosevelt for at least one of his African safaris. In a 1950 profile of Ernest Hemingway, The New Yorker’s Lillian Ross accompanied the novelist on a shopping trip to Abercrombie. (For a long time, it was believed that Hemingway took his life with a double-barreled shotgun purchased at Abercrombie, but recent evidence suggests otherwise.)

Eventually, however, Abercrombie’s cachet faded, and in 1978, Oshman’s, a now-defunct Texas sporting-goods chain, acquired the Abercrombie name for a paltry $1.5 million. When it gave up on the brand, Abercrombie was pawned off to the Limited and its deep-pocketed CEO, Leslie Wexner. Jeffries was Wexner’s hire, and his task was clear: repackage an aging clothing line for a new generation.

Jeffries did not jettison the Abercrombie brand altogether. Instead, he built on its history, proudly emblazoning “1892”—the year David T. Abercrombie opened his first shop, on South Street in lower Manhattan—across sweatshirts and ball caps. His A&F, as it became known, was woodsy and pedigreed (oxfords, cable-knit sweaters) but proudly athletic too (hence all the shredded denim and pre-faded cotton). He had no use for what he termed “cynicism.” The Abercrombie world was one of “wonderful camaraderie, friendship, and playfulness that exist in [the teen] generation and, candidly, does not exist in the older generation,” he has said.

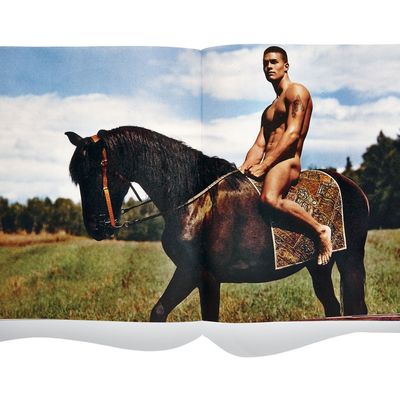

Above all, Jeffries, who was once married but is now openly gay, sought to sell an image of American beefcake sexuality as he saw it: a world of hairless, amply muscled men tussling in a pastoral Eden. That this world was so highly homoeroticized—the roughhousing in the catalogues seemed perpetually on the point of turning into a full-on orgy—is one of the most poignant ironies of his success. He was persuading straight jock teenagers to buy into a gay man’s fantasy of a jock utopia.

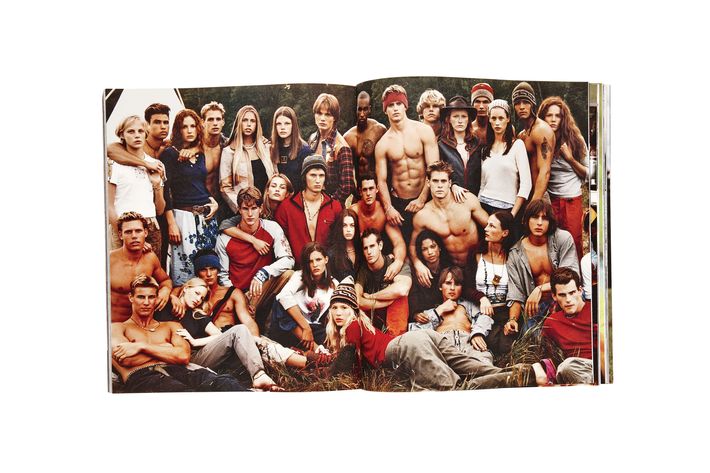

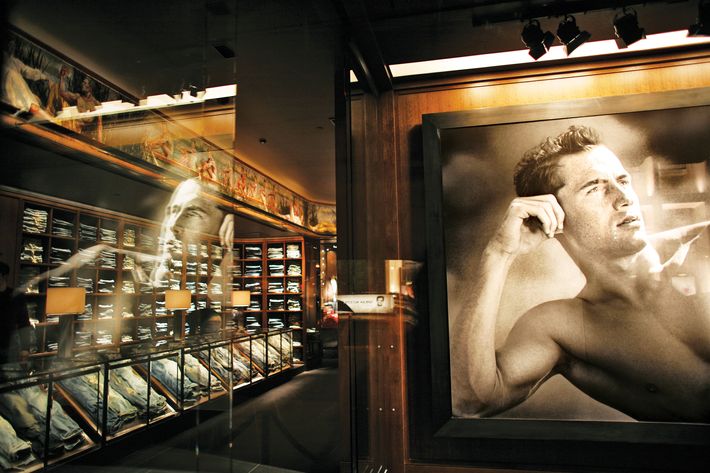

To help achieve this aesthetic, Jeffries turned to the photographer Bruce Weber. Among the subjects featured in early Abercrombie posters and catalogues were pre-fame Jennifer Lawrence, January Jones, Channing Tatum, and Ashton Kutcher (the last appeared in the midst of a scrum of lithe, toned man-children in plaid boxer shorts). “Part of Mike’s genius,” says Craig Brommers, the head of marketing at Abercrombie, “was in pioneering the most dramatic retail theater in the business.” In an Abercrombie store, the music was always deafeningly loud, the people were always good-looking (and often blond), the lights were always dim, and the pre-wrinkled apparel was always expensive.

Should there be any misconceptions about the intended consumer, the company was reluctant to discount their merchandise or to even invest significantly in an outlet strategy. Abercrombie clothing was aspirational. It was created, Jeffries has said, for the “attractive all-American kid with a great attitude and a lot of friends. A lot of people don’t belong [in our clothes], and they can’t belong. Are we exclusionary? Absolutely.” Jeffries has subsequently been pilloried for these remarks, but he was exploiting an understood weakness of the teenage shopper at the time—they wanted to belong.

In 1996, the Limited took Abercrombie public. The company was coming off four straight years of growth and had hit annual revenue of almost a quarter of a billion dollars. Jeffries took on a dual role of CEO and chairman of the board. Shareholders may have owned the company, but Jeffries ran it like a personal fiefdom. “Life stops and starts with what Mike Jeffries says,” one former employee told me. “There is nothing that is not shown to him, and there is nothing that he does not know about.”

Jeffries and a couple of trusted lieutenants sit at one end of the conference room; designers with samples and marker boards covered in sketches are at the other; and Jeffries offers his rapid-fire verdicts. And every week Jeffries strolls through the mock retail storefronts at the Ohio headquarters, signing off on the floor sets. He is said to trust deeply in rituals and talismans, such as a pair of lucky loafers he was known to wear while perusing financial reports. In the past he has insisted on never passing staff members in stairwells and walking through revolving doors twice.

Corporate employees are encouraged to dress casually in artfully distressed Abercrombie jeans and oxford shirts bearing the familiar moose logo. “There’s this fetishistic attitude—you want to demonstrate as much allegiance to the brand as possible because that’s what makes Mike happy,” a former designer told me. The designer recalled once showing up to a meeting wearing black jeans and leather-soled shoes. “Mike stared at me like, The nerve of this guy! He couldn’t stop looking at my shoes. I figured out that if you didn’t toe that line, you’d end up being alienated.”

A similar set of guidelines governs life at Abercrombie retail locations, where employees are required to follow the strictures of the glossy “Look Policy” book. “Sunkissed” hair, for instance, is permitted, while a hairstyle that features “chunks of contrasting color” is not. Skinny jeans should be cuffed at one and a quarter inches; the strings on peasant blouses should remain untied. The employees are encouraged to look as much like the people in the catalogues and posters as possible—a dictate that Jeffries himself seems to take to heart. One former employee, referencing the extensive cosmetic procedures Jeffries has undergone in recent years, told me that “Mike is physically trying to emulate the same models that he hires. In his head, that’s how he sees himself.”

In many ways, Jeffries’s most impressive accomplishment was not the signature Abercrombie style but the signature Abercrombie attitude, with its bluntly brash appeal. As one former employee put it, “The only bad news was no news. Controversy was what you wanted.” Consequently, the list of PR disasters past and present is too lengthy to fully detail, but the more notable flare-ups include the following: the quickly recalled line of Asian-themed T-shirts, which featured men in rice-paddy hats and cartoonishly slanted eyes; a line of thongs, marketed to girls as young as 10, with the words wink-wink on the crotch; an issue of A&F Quarterly that included a user’s guide to having oral sex in a movie theater; and the disingenuous joke-apology to critics that appeared in the same periodical in 2003: “If you’d be so kind, please offer our apologies to the following: the Catholic League, former Lt. Governor Corrine Wood of Illinois, the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund, the Stanford University Asian-American Association, N.O.W.”

In 2010, Michael Stephen Bustin, a former pilot of the Abercrombie corporate jet, filed a lawsuit against Abercrombie in a Philadelphia federal court, claiming he’d been unfairly dismissed because of his age. (He is in his mid-fifties.) Abercrombie & Fitch settled with Bustin, but not quickly enough to prevent the disclosure, by Bustin’s lawyers, of a 40-plus page Abercrombie “aircraft standards” manual, a copy of which leaked online.

Included in the manual are rules on crew apparel (the male staff, hand-selected by a New York modeling agency, were to wear a “spritz” of Abercrombie 41 cologne and boxer briefs under their jeans), the specific song to be played on return flights (“Take Me Home,” by Phil Collins), and the way the toilet paper in the aft lavatory should be rolled (never exposed; end square neatly folded). If Jeffries makes a request, the crew is always to respond with “No problem” instead of “Yes” or “Sure.”

Most striking was a guideline that stipulated that Jeffries’s longtime partner, Matthew Smith, was to receive copies of daily sales reports. Officially, Smith, who is British, is not an Abercrombie employee, but a recent BuzzFeed report alleges that he “wields vast influence over the retailer’s operations and strategic direction”—a development that is said to rankle many top Abercrombie executives. According to BuzzFeed, Smith has gone so far as to help select overseas locations for future Abercrombie stores. (An insider told me that “Matthew has no decision-making authority inside the company. He travels extensively with Mike and has some insights on real-estate matters that are often really valuable, but that’s the extent of it. All these articles greatly exaggerate the issue.”)

Jeffries does not hide his sexuality, former employees say, but he is not particularly forthcoming about his personal life. The extent of his glad-handing is the regular dinners Jeffries and Smith host for designers at their Ohio mansion. Models with the “Abercrombie look” are brought in to valet the cars, and a bartender serves cocktails in the living room. There are Bruce Weber books on the coffee tables, and the dogs, Ruby, Sammy, and Trouble, run freely, helping to break the ice. One attendee told me that Smith is charming and “age appropriate” (he’s in his early fifties). The couple are amiable hosts, the attendee said, but rarely engage in anything more than basic party chatter. “And then at some point, you get the message: ‘Okay, thanks, time for you to go home now.’ ”

Until relatively recently, Abercrombie’s numerous press scandals followed a predictable pattern: a flood of petitions and angry phone calls; an army of talking heads on cable TV complaining about the pernicious influence of the brand; and then silence. Consumers seemed to accept that Abercrombie’s gleefully offensive vibe was part of the package, and the company’s bottom line was never truly threatened.

But sensibilities have since evolved; casual prejudice is not as readily tolerated. Today’s teens are no longer interested in “the elite, cool-kid thing” to the extent that they once were, says Gordon, the Michigan professor. “This generation is about inclusiveness and valuing diversity. It’s about not looking down on people.” And with the help of social media, for the first time critics have succeeded in putting Abercrombie on the defensive. Last year, blogger Jes Baker drew blood with her spoof photo series “Attractive & Fat,” which satirized the iconic Bruce Weber images. A video of activist Greg Karber distributing Abercrombie clothing to homeless people has been viewed upwards of 8 million times on YouTube.

Partially in response to these campaigns, the company has sought to reach out to demographics it previously ignored. A line of plus-size clothing is reportedly in the works; young activists have been invited to Ohio to discuss Jeffries’s more outlandish comments. (A spokesman steered me to a recent report from the Human Rights Campaign Foundation, which gave Abercrombie a perfect score on its 2014 Corporate Equality Index.) And the company has partnered with the Christian charity World Vision to distribute millions of dollars of clothing to poor families.

Jeffries, for his part, seems to have been caught off guard by the changing tide. And no wonder, says someone who knows him well: “He’s created his own world out there in Ohio, and in that world, he’s the most important person.” Where once he was viewed as tolerably eccentric but undoubtedly brilliant—and tremendously good for the company—now his idiosyncrasies seem less forgivable. Instead of contributing to Abercrombie’s image, the scandals now appear to detract from it.

Since 2009, Abercrombie has closed 170 retail storefronts in the U.S.; it says it will continue the closures for the next few years. “The rationale for this is very obvious,” David Leino, Abercrombie’s senior vice-president for global real estate, has said. “The continued shift to customer spending online will make this necessary, especially in underperforming malls.” Meanwhile, Abercrombie will subtly change the way it does business in some of its existing shops, removing the space-hogging wood “porches”—meant to evoke a California surf shack—and the louvered shutters at some locations that once kept stores so cloistered and exclusive.

“I think we have to take the strongest part of our brand DNA and evolve it to be more relevant to a younger generation of consumers,” says Craig Brommers. “We don’t think this is a drastic repositioning, but we are very aware we need to evolve our brands.” Abercrombie, he continued, had been conducting in-depth research with teen shoppers, whom Brommers believes to be more ecumenical in their tastes than past generations and often more budget-conscious. “But we also know that teens are willing to spend a little more on quality staple items, such as denim, flannels, and outerwear.”

No one should expect Abercrombie to start offering biker jackets and patterned kimonos, both of which are included in H&M’s spring line—the essence of the Abercrombie aesthetic will remain unchanged. But the new Abercrombie will be less loud and less reliant on highly visible logos and branding. And in a distinct step away from the tactics encouraged by Jeffries a decade ago, there will be more variety in sizing and pricing. “We have a positive story to tell,” one executive told me. “How that story is communicated to the consumer is an ongoing strategic question.”

Earlier this year, Abercrombie opened a Hollister at the Dubai Mall in the United Arab Emirates—the first step in what is expected to be a wider push across the Middle East. Already, Abercrombie has stores in 21 markets, including Japan (three stores) and China (six stores). The company says that, while it has to be careful about certain regional sensitivities—in the United Arab Emirates, Brommers hinted, photo marketing may be toned down—international expansion could, with time, make up for lackluster sales at home. Others aren’t so sure. “There is an opportunity there,” says Wendy Liebmann. The problem, she adds, “is that if you don’t have a successful brand at home, going global isn’t going to save you. People go online. They’re going to see the backstory.”

Where all of this leaves Jeffries is unclear. On paper, his contract extends through next February, but one source with knowledge of the negotiations said that he could be pushed out beforehand, possibly via a proxy contest—a hostile takeover spearheaded by a critical mass of shareholders.

More recently, the company appears to have started actively working on succession planning. Jonathan Ramsden, a Brit viewed by Abercrombie insiders as highly capable, was recently promoted from CFO to COO, and Abercrombie will soon install a pair of “brand presidents”—one for Abercrombie and the Abercrombie Kids line and one for Hollister.

“Mike built a brand that had a tremendous amount of longevity,” says one prominent shareholder. “What that tells you is there’s something there that people really like. But Mike hasn’t been able to evolve Abercrombie & Fitch or his team, and that’s not good for customers or shareholders.” The hope is that the new blood could change that. If it can, there’s still a chance that the global teen-apparel brand Jeffries helped build could find its footing again. If it can’t, Jeffries could find his legacy permanently tarnished.

“I guarantee you, we’re already to the point where that resurgence in the nineties is a Wikipedia talking point,” says Sozzi. “What we’ll remember Jeffries for now is for failing to change, for all the store closures, for the way employees were treated. And that’s unfortunate.”

*This article originally appeared in the February 17, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.