“Thanks to the Drudge Report, I was possibly the first person whose global humiliation was driven by the Internet,” Monica Lewinsky writes in Vanity Fair. And though her affair with Bill Clinton may have kicked off our modern era of sex scandal — and set the standard for the boom-bust cycles of denial and apology, sexist fascination, and pseudo-celebrity — a lot has changed since 1998. A presidential candidate made a sex tape. Two U.S. Congressmen resigned over flirtations with women they never even met. Slut-shaming entered the lexicon, but so did cyberbullying, sexting, and reality star. Sixteen years after Interngate, technology has managed a neat trick: It’s now possible to have a sex scandal that’s simultaneously more chaste in its execution and far sleazier in its aftermath. Anthony Weiner never got laid, but the woman who sank his mayoral campaign nevertheless made and marketed a Weiner-themed porno.

By comparison, the woman who had “oral-anal contact” in the Oval Office is the portrait of ladylike restraint. Monica also enjoyed a brief period of celebrity, of course (remember when she hosted a dating show?), but as America became increasingly attention-obsessed and media-optimized, she fell into an adult life “so silent … that the buzz in some circles has been that the Clintons must have paid me off; why else would I have refrained from speaking out?”

Today whore is a pejorative that has more to do with profiteering than promiscuity; the mainstream is learning, slowly, to be sex-positive, but there is no corollary term for empathizing with unabashed attention-seekers. And so Monica’s claim that she “turned down offers that would have earned me more than $10 million” becomes her redemption, a form of abstinence she uses now to prove her virtue. But she decries this double standard, too: “Not lying low exposed me to criticism for trying to ‘capitalize’ on my ‘notoriety.’ Apparently, others talking about me is O.K.; me speaking out for myself is not.”

Capitalizing on notoriety is easier than ever. During Monica’s decade of silence, it actually became a viable career: In the aftermath of Tiger Woods’s sex scandal, porn star Gina Rodriguez founded a PR company dedicated to monetizing what she called “mistresses,” a catch-all term connoting not sexual contact but mere sexual notoriety. For clients ranging from Weiner’s sexters to Woods’s prostitutes to the adultery partners of Mel Gibson and Jesse James, Rodriguez has organized “mistress” nights at strip clubs, “mistress” photo opportunities, and dating-website endorsements. Six months after she went public as the recipient of Carlos Danger’s text messages, Rodriguez client Sydney Leathers invited a photographer to document a series of cosmetic-surgery procedures culminating in labia reduction. She had wanted to sell the cut-off remnants of her labia, too, but U.S. laws about “medical waste” thwarted her.

Suddenly, Monica’s foray into designing tote bags seems quaint.

Some of Monica’s relative classiness may, in fact, be a matter of class. When employment was hard to come by, Lewinsky writes that she fell back on “loans from friends and family.” She was, after all, the kind of twentysomething who worked at the White House, a distinction nobody in Gina Rodriguez’s “mistress” club can boast. (Rodriguez does, however, represent White House party-crasher Michaele Salahi.) But who knows how things might have been different if her scandal had unfolded in the age of the selfie. Today, the feedback loop for sexual schadenfreude has been paired with a relentless egging-on. A decade ago, Monica’s turn at TV stardom had her playing the “stout matron” of a family-friendly dating show; today, notorious women are more likely to play the warbling reality star sobbing through false eyelashes. Would she have filmed ads for Jenny Craig, or something more tawdry?

Even without modern opportunities for post-scandal livelihood, Lewinsky has been branded by the scandal that made her famous. She theorizes that some of her problem arose from the scandal taking place before she’d had a chance to develop her adult identity:

Unlike the other parties involved, I was so young that I had no established identity to which I could return. I didn’t “let this define” me — I simply hadn’t had the life experience to establish my own identity in 1998. If you haven’t figured out who you are, it’s hard not to accept the horrible image of you created by others. (Thus, my compassion for young people who find themselves shamed on the Web.) Despite much self-searching and therapy and exploring of different paths, I remained “stuck” for far too many years.

Now 40, Lewinsky is no longer a naïf playing at stardom. She’s one of the first adults to have gone through the modern gauntlet of mass sexual scrutiny. The impetus for her essay, she says, is a desire to aid the victims of cyberbullying and to help dismantle America’s “culture of humiliation.” I believe she is genuine in that desire (in the depths of her misery, Lewinsky says she contemplated suicide), but I also can’t help but marvel at what may be That Woman’s savviest self-branding decision yet: In the age of Sydney Leathers, she is aligning herself with Tyler Clementi. Monica’s legacy will be about sexual politics, not celebrity.

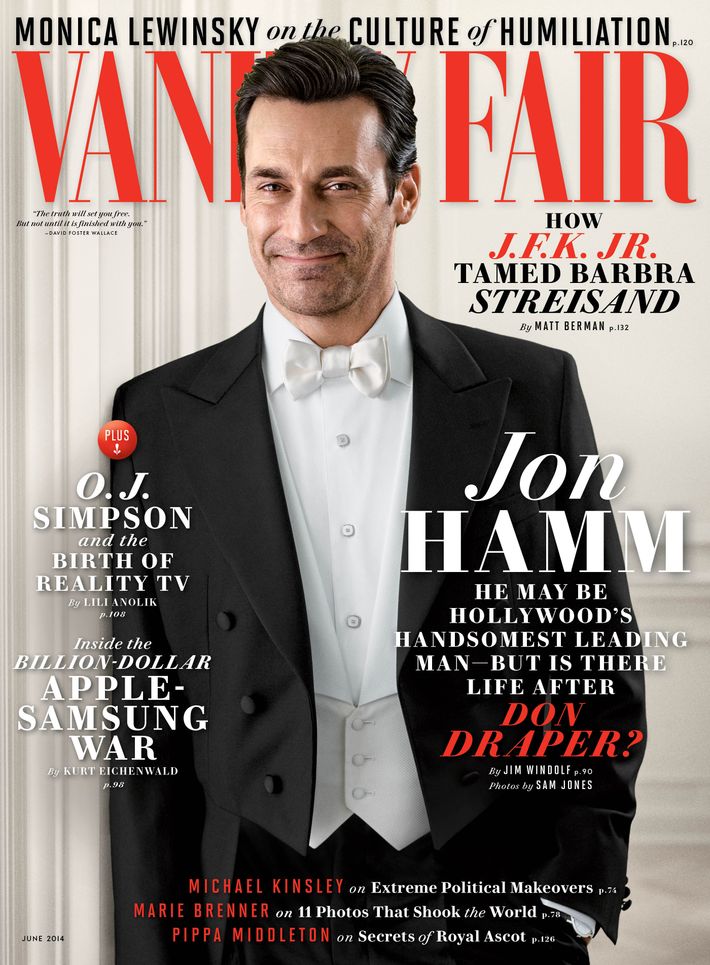

“So far, That Woman has never been able to escape the shadow of that first depiction,” Lewinsky writes. “I was the Unstable Stalker (a phrase disseminated by the Clinton White House), the Dimwit Floozy, the Poor Innocent who didn’t know any better.” Initial reactions to Lewinsky’s appearance in Vanity Fair played into that trope: Yesterday, Monica’s media nemesis Maureen Dowd (“Moremean Dowdy, as I used to call her”) described the ex-intern as “striking yet another come-hither pose.” If sex is on sale here, I don’t see it. If anything, Mark Seliger’s casually glamorous photos are remarkable for their chastity. When Seliger photographed Rielle Hunter for GQ, the adulteress posed in bed with her pants off. In Vanity Fair, Monica’s virginal white dress looks like something Audrey Hepburn would wear.

“The last time I encountered Monica was at the Bombay Club, a restaurant nestled between my office and the White House,” Dowd reflects. “After requesting that the piano player play ‘Send in the Clowns,’ she leaned in with me, demanding to know why I wrote such “scathing” pieces about her.” Today, Monica might choose a more dignified song. (“Survivor”? “Roar”? Or “Cathy’s Clown” by the Everly Brothers: “When you see me shed a tear and you know that it’s sincere / Don’t you think it’s kinda sad that you’re treating me so bad?”) But she’s leaning in again, and to a tune of her own choosing.