Patricia Lockwood is the author of the viral poem “Rape Joke.” It is a national treasure that energized contemporary poetry — a viral poem — and provided the perfect, final word in the rape-joke debate, if we can call it that. For that reason alone, “Rape Joke,” and Lockwood, should enter the canon forever and be required reading for all U.S. citizens.

The rape joke is that you were 19 years old.

The rape joke is that he was your boyfriend.

The rape joke it wore a goatee. A goatee.

Imagine the rape joke looking in the mirror, perfectly reflecting back itself, and grooming itself to look more like a rape joke. “Ahhhh,” it thinks. “Yes. A goatee.”

No offense.

(Re-read the rest at The Awl; it is better than you remember.)

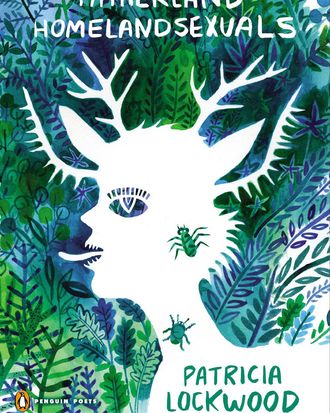

A lot of people feel this way — more than 40,000 follow her on Twitter — so it probably should not have been surprising that Lockwood’s new book of poems, Motherland Fatherland Homelandsexuals (which contains “Rape Joke”) was the source of a minor backlash dustup this week. After a big, glowing profile of Lockwood in The New York Times Magazine, The Toast wrote that her book had been given a sexist review by The New Yorker online. The Awl further observed that only men had been assigned to review it.

In Adam Plunkett’s New Yorker review, he condescendingly “worries” that Lockwood has succumbed to the “temptation” of “constant reinforcement” Twitter offers, and this need to be well liked and heavily “liked” has shaped her poetry for the worse.

I also don’t mean that Twitter is stupid but, rather, that it rewards careful phrasing, careful impersonating, brisk readings of cultural attitudes — in short, rhetoric. Her crowd claps loudly at jokes, especially provocative ones, and the lowest common denominator feels provoked to respond, begetting further jokes at their expense.

Calling Lockwood a Twitter poet has the same effect as calling a woman who writes novels about other women a chick-lit author. It gives men — in particular the serious ones still largely in control of prizes and grants and review sections — permission to ignore her work. It’s not an explicitly gendered label, but the negative connotations of the Twitter poet overlap with those of the chick-lit author, the women’s magazine editor, and the pop starlet. If she is successful, it is because her product cannily catered to the preexisting demands of the crowd, not her own intellectual or artistic vision. I think women are especially sensitive to this critique, because it mirrors one often made of us sexually: If we are popular and make ourselves accessible to many, we must be whores.

Because of the commercial success of chick-lit authors and Twitter poets — compared to writers who are shaped by the niche, exclusive demands of M.F.A. workshops (Lockwood never even got a bachelor’s degree) — it’s easy to see critiques like The Toast’s as “bellyaching,” as Jeffrey Eugenides once put it. Fuck prizes; get money, I often think. But Plunkett, sneakily, did something more sexist than genre-pigeonholing. Using Lockwood’s Twitter as an online proxy, Plunkett managed to review Lockwood’s personality, not her poems. She is far from the first female writer to be evaluated in this way (Marisha Pessl comes immediately to mind), nor is she the first female author whose social-media output has been taken as a sign of literary apocalypse. Remember when Jonathan Franzen listed “Jennifer Weiner-ish [Twitter] self-promotion” among the things “wrong with the modern world”?

Having read Motherland, and being a woman, this my review: It is a fantastically weird little book that makes funny and creepy almost-fables out of sex and gender and the business of writing. That it is all this to someone who follows neither Lockwood’s poetry scene nor her comedic Twitter personality is a virtue. But I can also say that Plunkett’s attempt to link Lockwood’s Twitter persona to her poems (“the zany comic sexuality … is never more nuanced than the brutish, broish caricature she tweets about and that tweets back at her her poems”) is weak. It misrepresents what the majority of the poems in the book are about (alas, not men!), and misunderstands the ones that are.

For example, “Revealing Nature Photographs” addresses a person who, like an adolescent boy rooting around in his dad’s stuff, discovers a “stack of revealing nature photographs.” “Nature” is “into bloodplay” and “on all fours” and “wants you to pee in her mouth.” “Nature turned you down in high school. / Now you can come in her eye.” “This is addressed to a man but written for people to laugh at him, even if the poem doesn’t evoke Nature well enough to think of her as any sort of woman, let alone one whom you repressed your anger toward,” Plunkett complained. “But the subtleties of men’s desires were never the point.” No, for once, they were not. Lockwood is, however, playing with poetry’s clichéd marriage of women and nature by reversing directions. What if the prosaic ways men (not all men) describe women in real life and through pornography were applied to capital-N Nature?

In fact, my favorite poem in Motherland offers precisely the nuanced, emotionally deep take on masculinity Plunkett demands of Lockwood (a request not often made of male poets about femininity). “List of Cross-Dressing Soldiers” begins as just that, ticking off famous female soldiers in history, before it becomes about her brother, who served multiple tours in Iraq and Afghanistan, and his military machismo. “Women should not be over there,” he tells her. “I watched people burn to death. They burned to death in front of me.” She then contrasts his benevolent sexism to the feminine bond between him and his army buddies.“They passed the hours with ticklefights. They grew their mustaches together. / They lost their hearts to local dogs, / what a bunch of girls.” One of these friends was killed by a roadside bomb that missed her brother, she explains, “because of a family capacity for little hairs rising on the back of the neck.”

Trapped in a print book, I couldn’t fave or retweet Lockwood’s lines. Instead, they left me crying on the subway. But maybe that was just some hormonal thing.