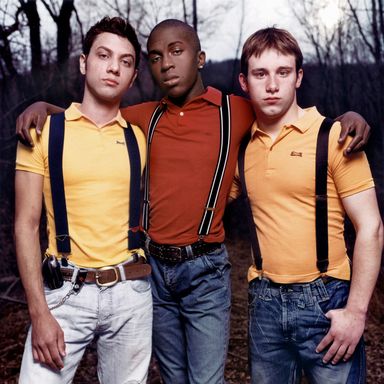

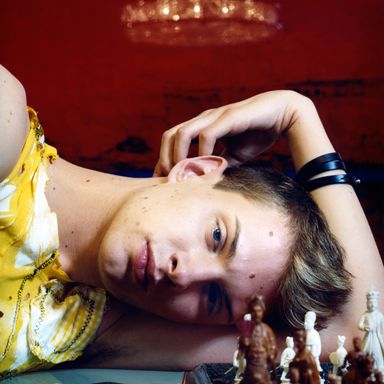

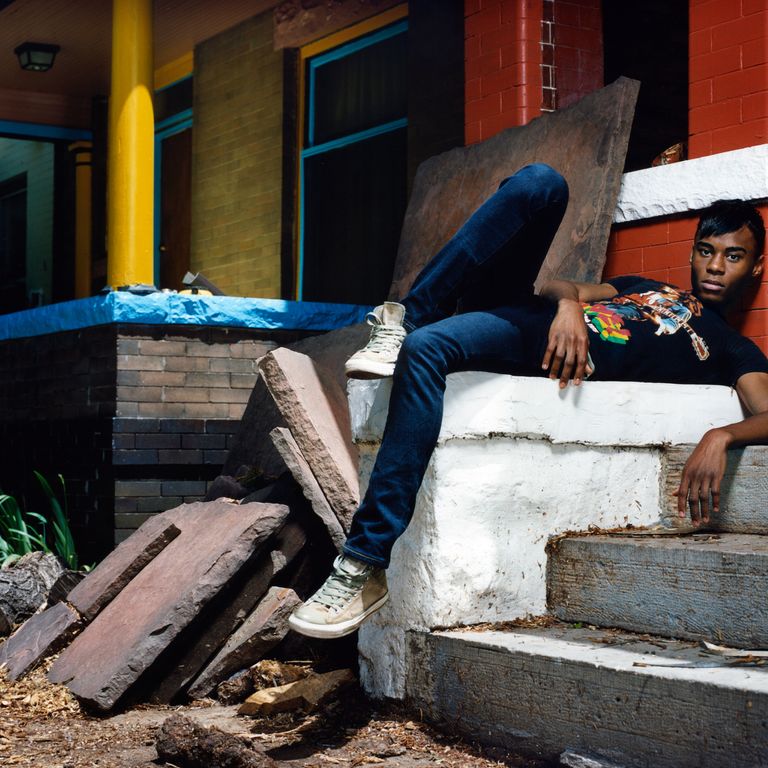

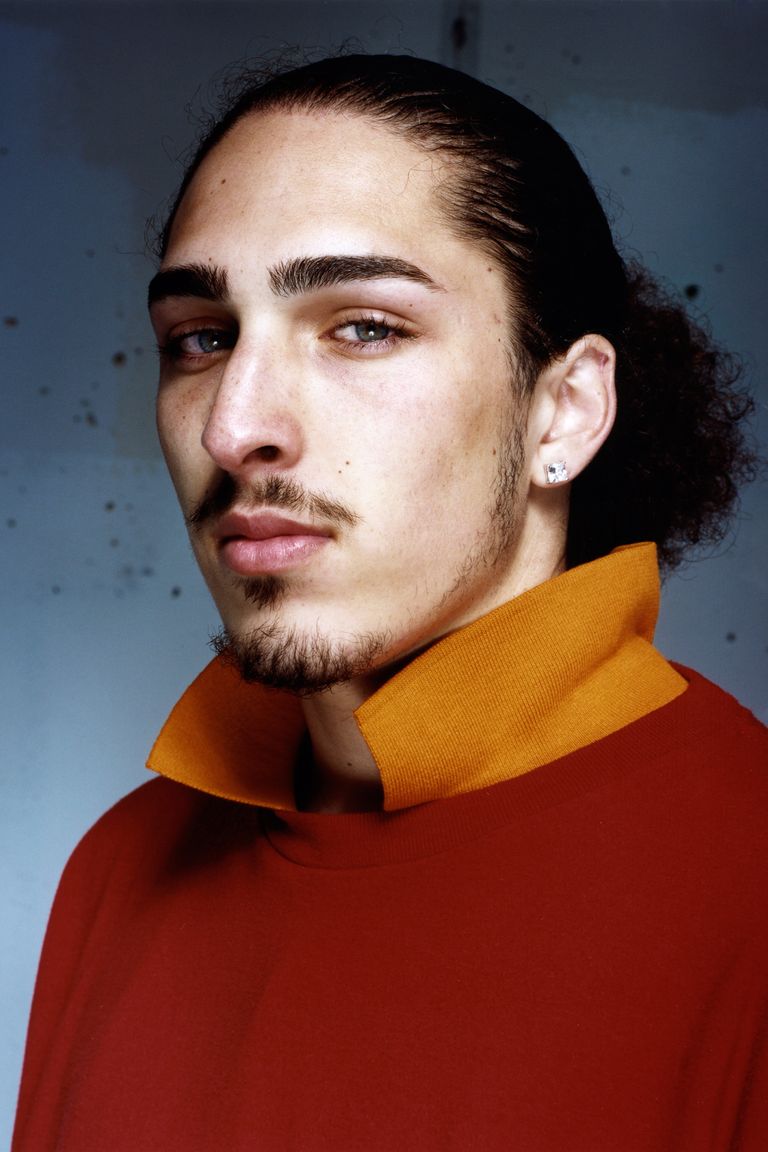

See M. Sharkey’s Poignant Portraits of Queer Youth

Today marks the U.S. debut of “Queer Kids: Coming Out In America” — a collection of portraits of LGBT youth from across the country by New York–based photographer M. Sharkey. The exhibit, which will be on view through the beginning of January at the Stonewall National Museum in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, features large-scale photographs accompanied by interviews about the subjects’ identities and experiences. Since 2006, Sharkey has been traveling across the country and through parts of Belgium to photograph kids in their hometowns and speak with them about their experiences coming out. The Cut spoke with him about what’s changed since he started.

What inspired you to start this project?

Well, I started shooting in the early 2000s, and I felt like I wanted a project I could do for a long period of time that I could focus all my creative energy on — something that I felt passionately about, that would sustain prolonged interest. I was a gay teen myself, and it was sort of a tough time, in the ‘80s, to be a gay teen. I wished things had been different, and that I had had the opportunity to be more open about my sexuality. And I felt like this was an opportunity for me to give voice to some of these kids who were demanding to be heard. It’s hard to remember how much things have changed even over the past decade. Even only eight years ago, this topic was really new — and at that time it required an incredible amount of courage for these kids to stand up.

How have things changed since you first started? Has that influenced your work?

I think that how I approach my subjects has changed. In the beginning maybe there was a slight trepidation on my part, because I knew that the subject was sensitive enough that if it weren’t approached properly, it could result in continued hardship for some of these kids. I feel like it’s a lot different now. The kids have a lot more pride in their identity, and they feel a lot more strength from the communities that have slowly begun to emerge. I think there’s a lot more bravery in the way that they present themselves to the world.

The kids are always very excited to be photographed, because it’s a moment for them where they really get to be themselves — and they can proudly be themselves. I think there’s still a little bit of fear and apprehension that they have to show the world who they are — I mean, that takes a lot of courage no matter what your identity is, but especially when you’re part of such a marginalized and potentially vilified group.

How do you find the kids that you photograph?

Initially, it was through gay organizations, like GLSEN or the GSAs that started popping up across American high schools in the mid-2000s. And then the project kind of got some legs and kids started contacting me, and occasionally I have parents who contact me with kids that they feel would be right for the project.

I think the thing that initially draws me to them is the way that they look and the way they are presenting themselves. If there’s something that rings undeniably individual about them, where you’re like, they just have their own ideas about style and identity, that’s more interesting to me. I’m drawn to kids where I’m like, “Oh, that kid has something to say,” and I want to give them the opportunity to say it.

You also interview all of the kids that you photograph, right?

Yeah, the textual component of the project is essential. It often gets overlooked because the images are easily digestible and they’re striking enough to stand alone, but it’s an important aspect to the project that you get to hear their voice. I think it’s my favorite part, getting to sit down and talk with these kids and learn about their life. They come from all different walks of life, and they have all different kinds of experiences. When you grow up with that kind of adversity, or shameful secret that you’re trying to hide, or feel unsure about whether or not to tell — I mean, for some kids, the result is irrevocable and profoundly life-changing. I know kids who have been kicked out of their homes. But I think that most of them have this incredible resilience and youthful spirit.

They’re also at the age where you really start to develop a strong perception of yourself and your self in the world. I think for the most part, they feel pretty optimistic about the future. There’s definitely that hopefulness and the thought that things can change, and they can make a better world. Some of the kids I really, really admire, and I feel a real connection to. I stay in contact with a lot of them, because I think it would be really interesting to follow up with them as subjects at some point.

You’ve mentioned in other interviews that at the beginning of your project, the kids that you talked to were more likely to identify as either lesbian, gay, bi, or trans, and that now they tend to identify as queer. To what do you attribute that shift?

I think about this question a lot, and my views are still evolving. I think there was a tendency and desire for individuals to find a label that they felt most closely approximated an identity that they felt and then stick with it — and to find strength in that label itself. Today, it feels like the consciousness has expanded and not just kids, but people generally, feel like they don’t have to identify as any one particular thing. I think the more that we understand gender, the more we come to the conclusion that identity is fluid, and there’s a great sense of power that comes from the realization that you don’t always have to be masculine or feminine or gay or lesbian. The term queer is more suitable to that fluidity.

But I also think that gender expression is really interesting, and it’s a force of great pleasure for many people to be able to express themselves in a very masculine or very feminine way. I don’t think that’s going anywhere. We really enjoy it, we find great pleasure in it, and a lot of our sexual attraction comes from strong expressions of gender. But, what we might realize in the future is that whether you’re born a man or a woman, or something in between, you still have the ability to express yourself in a multitude of ways. I think that’s what the queer ethos embodies.

Are you still working on the series?

Yeah. My hope is to be able to continue this project in other parts of the world. So far I’ve shot in the U.S. and Belgium, and I’d love to be able to do the rest of Europe and South America. I think that in a few years, this kind of project could visit all different parts of the globe, even the most conservative ones. I love the photography part of it, but it’s also just great to see all these young people all over the world — who are changing the world. I feel like it gives me access to a glimpse of the future that I normally wouldn’t have the privilege of seeing.

Click through the slideshow for a look at Sharkey’s portraits and interviews with queer youth across the country.