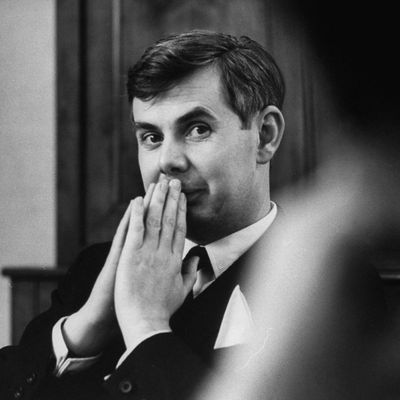

When longtime Women’s Wear Daily editor John Fairchild passed away today at 87, the paper was the first to report the news. Mr. Fairchild, as everyone called him, was a proponent of being the first at everything. Under his leadership, WWD, which began as a single page in the men’s fashion trade DNR, evolved from a trade paper to a must-read inside and outside the industry. (“Get the bacon” was his stock phrase to his reporters.) In contrast to the toothless quality of most fashion coverage today, WWD under Fairchild took no prisoners. He was unafraid to publish negative reviews of collections, which earned him the nickname “Unfairchild.” And his approach to covering fashion elevated designers and socialites to star status — while, all the while, he spewed his memorable bons mots.

“I have learned in fashion to be a little savage,” he wrote in Chic Savages, his industry version of Capote’s Answered Prayers. The Newark-born Fairchild entered the family business in 1951, and served as publisher and editor-in-chief from 1964 until his retirement in 1997. Upon taking over, he began to push the boundaries of a hermetic industry. When the paper was snubbed by Paris houses who wanted to keep their designs under wraps from American copycats, he sent sketch artists to peek in the windows of designers’ ateliers. Some of his reporters pretended to be messengers, ferrying dresses from atelier to runway — or they’d be faux-couture clients, inquiring about the clothes. The newer, gossipier, wittier WWD drew readers from outside the industry, leading Fairchild to found W magazine, which began its life as a broadsheet-style supplement to the newspaper, in 1972.

Oscar de la Renta once told Vanity Fair of Fairchild’s approach, “If the story was about you, you hated it, and if the story was about somebody else, you enjoyed it.” (As Fairchild’s successor Patrick McCarthy put it, in a New York cover story in 1997: “WWD kicks everybody in the balls eventually.”) He was known for his feuds with designers — a long list that included Cristóbal Balenciaga, Yves Saint Laurent, Giorgio Armani, Azzedine Alaïa, Bill Blass, Pauline Trigère, James Galanos, Perry Ellis, and Geoffrey Beene. (In 1988, Trigère even took out a “Dear John”–style ad in The New York Times Magazine to ask for rapprochement. The ploy did not work.) But even as he critiqued them, sometimes mercilessly, by making their personalities and looks the focus of his coverage, he created the modern climate where Marc Jacobs stars in nude ads for his fragrance and Michael Kors is on everyone’s TV. He made stars of favored talents like de la Renta (“A lot of what I am today I owe to John Fairchild,” he told Vanity Fair), while cutting down the likes of Beene, whose shows the paper refused to review for decades, after a tiff that began when Beene failed to provide them with an advance look at Lynda Bird Johnson’s wedding dress.

He also cannily covered high society, creating the “Eye” column and an “In and Out” list. For the “Eye,” he would have photographers snap “the ladies who lunch” (a phrase he came up with, not Stephen Sondheim) outside La Grenouille in their Chanel — call it an early version of street style. He was the first to call Jackie Onassis “Jackie O,” then incurred her wrath some years later by calling her “Tacky O.”

Mr. Fairchild’s influence did not wane with his retirement. I began working at WWD a decade after his departure, and while I never met him, his presence was very much felt there. He would regularly phone its top editors from his home in Gstaad, and he continued to write his column for W, under the pseudonym Countess Louise J. Esterhazy. The publication was quietly guided by his preferences, even the unusual ones — on a shoot, I remember someone telling me he hated to see models’ armpits, and thus all hands-above-the-head shots were verboten. He continued to give interviews that were far more fascinating than most Hollywood actors’ — in 2010, he told the New York Observer, “If I see another movie star in a fashion magazine — it’s ridiculous! It’s a nightmare … When I hear the word buzz, it reminds me of a chainsaw.” He may not have liked the term, but he generated plenty of it during his career.