There’s a new theme every day on It’s Vintage. Read more articles on today’s topic: The Belgian Invasion.

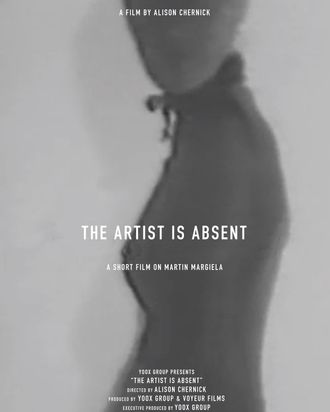

How do you make a documentary about someone who’s taken pains to remain out of the spotlight? Alison Chernick set out to do just that. Known for her documentaries on Jeff Koons, Matthew Barney, and Roy Lichtenstein, the filmmaker had never addressed the world of fashion in her work. But for her new short documentary, The Artist Is Absent — premiering tomorrow at the Tribeca Film Festival — she took on easily the most elusive subject in fashion: Martin Margiela. The film will also premiere on Yoox, the Corner, and Shoescribe on April 27. In advance of the premiere, Chernick talked to the Cut about making the crossover from art to fashion and the challenges of directing a documentary about one of the least-documented public figures out there.

How did you decide that you wanted to pursue this topic?

I have a background doing documentaries on artists. I did one on Jeff Koons, and one on Matthew Barney, and after those two films I thought, I’m going to work on fiction. Margiela was always somebody that I said I’d make an exception for. Maybe a year or two later, I ended up becoming friends with one of his ex-designers. He ended up putting me in touch with the maison, who looked through my past work, and I had also emailed with Martin. It just all became something that needed to happen. He said, “You’re the right person to do this” based on my past work, and then I got the exclusive rights.

The title The Artist Is Absent is apropos for Margiela because anonymity has been such a big part of his career in terms of both how he stayed out of the spotlight and with the models wearing masks or obscuring their faces in various ways. You’re dealing with someone who was almost never photographed, who gave so few interviews — how do you tackle a subject like that?

I realized that there was no press and no footage of Martin, so that was obviously going to become a major challenge. And then it was like, “How am I going to tell this story?” You always want to avoid talking heads, but in this case the talking heads were sort of the most interesting part and these critics had all put in so much thought into this already. So my job became choreographing and curating these voices and finding the best way to tell the story. And the maison had amazing footage that I couldn’t find elsewhere.

Did you have contact with Martin at all?

I did have contact with him, once, briefly. He actually gave me a list of people to interview that he thought would be good. I talked to some of them, I did not get to all of them. But it was interesting to have that dialogue. Had I done a longer film, I would have tried to engage with him more, but this was a commission of a short film.

In the film, the curator of the Mode Museum in Antwerp says that Margiela is kind of the seventh member of the Antwerp Six. He graduated from the Royal Academy there at the same time they did. Do you think that he fits in with these classmates, or is he distinct from them?

They all graduated together and started to do their own shows and really put Belgium back on the map, creating a shift in fashion history in the late ‘80s where they were recycling clothing, using anything from car seats to trash bags. Ultimately [though], Martin didn’t want to be a part of a group — he wanted to be on his own and shortly after he moved to Paris and started working at Gaultier.

What made him so revolutionary as a designer?

He would take these classic bourgeois pieces and restructure them or alter them in a revolutionary way. The consumer recognizes it in some way, but it makes you think. He almost became the anti-designer.

Can you give some examples of familiar pieces that he reconceptualized?

He would put shoulder pads on the outside [of jackets]; he would turn sleeves inside-out and create capes, make a dress out of a trash bag, he would use a seat belt as a belt— really creative things.

He was an early adopter of “upcycling,” though it wasn’t called that at the time — reusing old garments and found items. And he’s known for this really intricate detail work — a lot of hand-painting, buttons, and beaded pieces.

His mother used to do that. She was sort of recycling vintage [pieces], reformatting them, and just having fun with it.

Looking at some of these collections and also talking to these experts about them, is there one that stands out to you as particularly noteworthy?

For the opening scene, I chose to showcase that one show [from 1989] that was outside Paris, in the suburbs, where the children ran with the models. It was just this wonderful initiation into his work and how he celebrates that community.

What do you think his impact is today? There was the H&M collaboration in 2012, and he’s very much referenced in pop culture, especially in rap lyrics. Even more people know about him because of both of those things. Do you think that Margiela vision is still around? Do you think it’s been watered down at all? Is it still relevant?

I think often what you see in the mainstream today is something Martin introduced 20 or 30 years ago, which is fascinating, like [denim with] frayed hems or unfinished clothing with seams on the outside, and it all feels so normal today, which is kind of amusing. Designers such as Alexander McQueen and Marc Jacobs clearly have been influenced by his work, and I think they even say that. And then craftsmanship is of utmost importance to his work. You asked if it was watered down — the style still remains.

This interview has been edited and condensed.