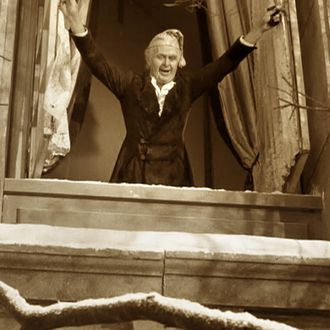

Mr. A was once a cautious and responsible corporate guy, a department head at a large company in Brazil. But after a stroke, he became so generous that doctors deemed the behavior pathological, by which they meant that it interfered with his ability to keep his job or manage his finances. Those doctors later reported Mr. A’s case in a 2014 edition of the journal Neurocase. Their write-up reads something like a real-life Ebenezer Scrooge story — albeit a version that takes place in Brazil and includes considerably more brain-scan imagery.

The patient: Mr. A was quiet and reliable, but not overly sociable; though the 49-year-old was close to his family, he counted few friends. He wasn’t a talkative guy, but he knew how to argue, “sometimes hotly,” the case report authors write, drawing from family members’ recollections. Though “he would never initiate an argument, [he] would reply strongly when challenged.”

The problem: Really, the problem was only a problem in the eyes of his family and physicians; Mr A, for one, loved his new life. But his family was worried. After his stroke, his personality seemed to have radically changed, and he was no longer the predictable and conscientious company man he’d once been. Instead, he became fixated on giving his money away.

He didn’t return to his old job after the stroke, instead turning his attention to the restaurant he started with his brother-in-law. But he soon drove the establishment out of business, because he rarely saw the point in charging customers for their meals. Mr. A also started looking out for the homeless children on the streets in his neighborhood, regularly stopping to buy them candy and soda.

His wife told his doctors that the family’s finances were spiraling out of control and that if it weren’t for her watchful eye, they’d be deeply in debt. Mr. A, on the other hand, was enthusiastic about his new approach to life and would get angry when his family or physicians questioned him. When asked why he hadn’t yet returned to work, he said he’d worked enough, and now he wanted “to enjoy life, which is too short.”

The diagnosis: Apart from the generosity, Mr. A was forgetful, had trouble paying attention, and said he felt depressed. Through the use of functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI (a way of measuring brain activity by tracking blood flow), doctors observed lower blood flow to Mr. A’s frontal lobe, which may indicate loss of executive function — that is, organizational skills, attention management, and, perhaps most relevant to Mr. A’s case, impulse control.

Increased generosity as a symptom of brain injury is unusual, but the case report authors write that it has been observed in some patients with dementia or Parkinson’s. “Because pathological generosity may lead to significant distress and financial burden upon patients and their families, it may warrant further consideration as a potential type of impulse control disorder,” the medical team writes in their report. Mr. A, on the other hand, had a different opinion on the matter. “I saw death from up-close,” he told his doctors. “[N]ow I want to be in high spirits.”