An Oral History of Legendary ’90s Rave Emporium Liquid Sky

There’s a new theme every day on It’s Vintage. Read more articles on today’s topic: Rave Fashion.

In the pre-internet 1990s, subcultures were distinctive and specific: If you were a raver walking the New York streets and you saw someone wearing big jeans and a Liquid Sky T-shirt, there was an immediate connection.

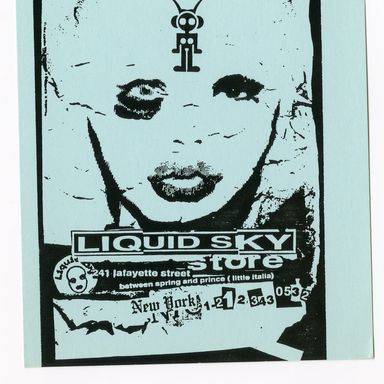

Just as Fiorucci is the exemplar of the 1980s alternative shop, Liquid Sky wasn’t a fashion brand as much as it was a paradigm of the ‘90s rave subculture. It originated with the indie film Liquid Sky — a pastiche of flying saucers, gender fluidity, and slutty New Wave looks that quickly developed a cult following when the film was released in 1982. Its influence reached as far as São Paolo, where then-husband and wife Carlos Soul Slinger, a veterinarian turned DJ, and former model/designer Claudia Rey, titled their cosmetics brand after it. Its success led to them opening Lajoa (“shop” in Portuguese), which sold the makeup along with Rey’s designs. In 1989, they moved to New York and opened Liquid Sky on 482 Broome Street, on the corner of Wooster Street, in a then-desolate Soho. As its most famous former clerk, Chloë Sevigny recalls, Liquid Sky “was never a store. It was a happening. It was a scene.” Here, an oral history of the store that forever changed Lafayette Street — and with it, the history of fashion.

Carlos Soul Slinger (co-owner of Liquid Sky): When we first opened, people would laugh and leave without buying anything.

DB Burkeman (DJ and A&R exec, then-owner of Liquid Sky’s basement store Temple Records): I was throwing a party called Orange underneath Kim’s Video on Avenue A. Rave culture hadn’t happened here yet. It was 1990. In walked Soul Slinger and Rey. They looked alien. A few months later, I heard that this weird little shop had opened in Soho.

Carlos: Since I was 6, I was asking, what the fuck is this universe? I always believed that there was something going on with our origins. Who are we? Is Darwin right? Is biology love? Always question. And the aliens can help save [us], in a way.

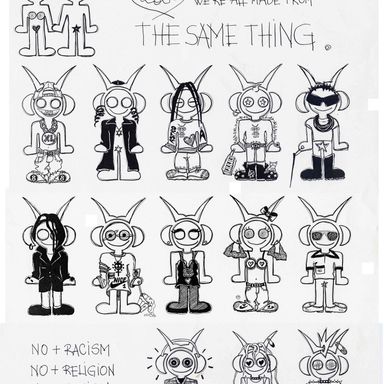

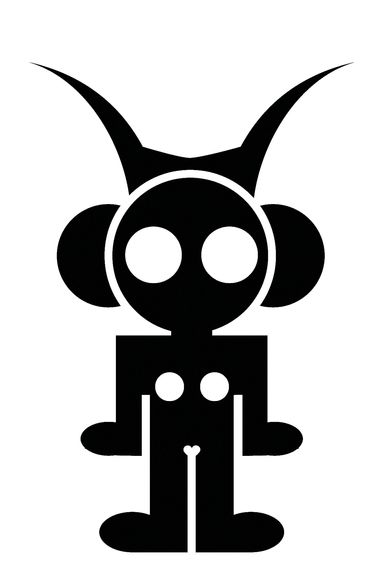

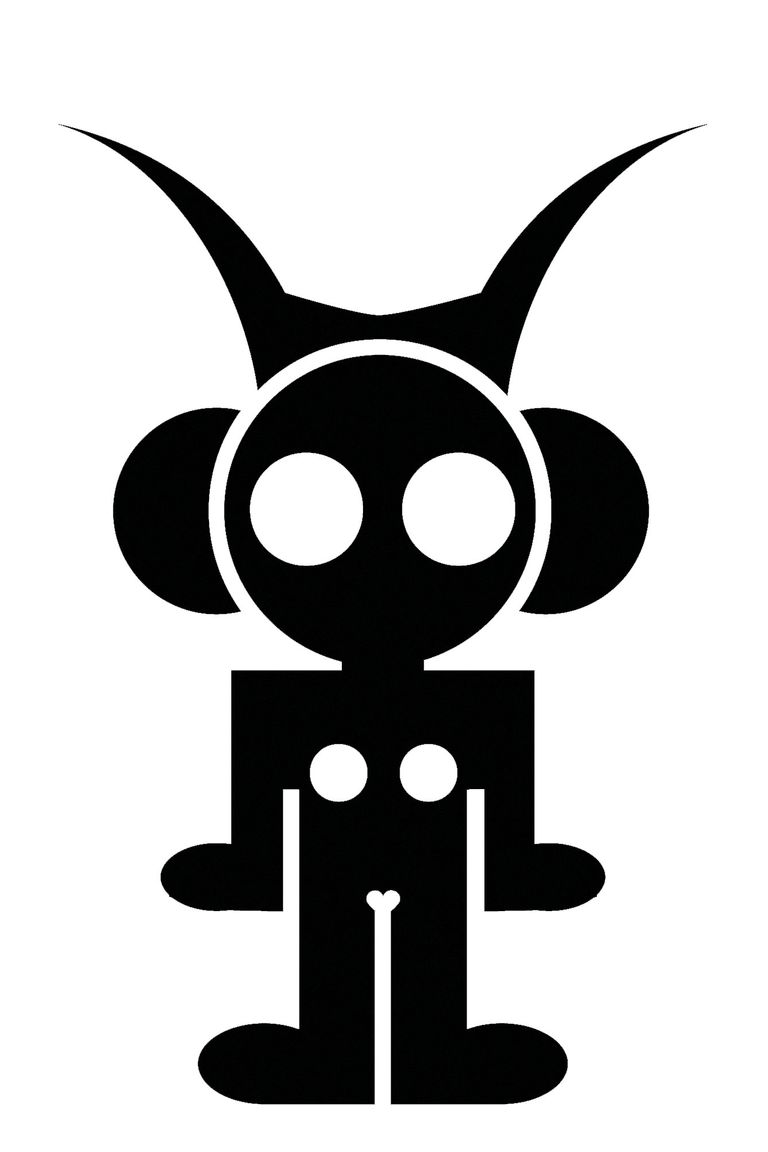

Rey and Carlos’s pro-alien ethos became the foundation of Liquid Sky, coalescing in the store’s logo, “Astrogirl,” an antennaed alien with a heart-shaped crotch. One of Rey’s most enduring designs was a pair of big jeans that had belt loops and an embroidered Astrogirl on the ankles. The back pockets reached almost to the knees. They’d come out in endless variations: orange camouflage, fake fur, etc. The most distinctive feature conceptually echoed Astrogirl’s heart crotch — a beeper pocket.

Rey: The beeper pocket was also for drugs.

In 1992, DB and Scotto opened the seminal NASA party at the Shelter, a club in a rundown part of Tribeca. It was the first weekly rave within a club in the city. Carlos spun experimental and ambient music in the “Liquid Sky Chillout Room.”

Peter Glennon (NASA doorperson and promoter): [Carlos] developed this cult in the back room, and through that, exposed people to his store.

In 1993, Rey and Soul Slinger ended their personal relationship. Carlos started dating Mary Frey, who was a doorperson at Limelight and Save the Robots.

Frey: Claudia was the one that was creating everything. It was a cool store. There was nothing like it. By the time I came, it was disjointed. Carlos and Claudia were freshly broken up, and I wasn’t really welcome in the whole situation.

There was a fire in the building in 1992, and the Soho store closed. Frey and Carlos found a space at 74 Lafayette Street for the second iteration of Liquid Sky. It had been an art space that the city had closed for presenting live sex shows in the vitrine. Carlos and Mary transformed it into a store in the front and their home in the back, building a platform in the stockroom for a bed. They lived there for two years. The new store’s design was dominated by a window of cascading water.

Frey: We started taking Astrogirl and the Liquid Sky idea to another level. After a while, Claudia started to accept it. She came onboard. It was bigger than what they had started. Carlos and I came up with the idea of this walkway, like you were going through the TWA tunnel with the Plexiglas. Then we built that space in the back like Star Trek, where in each little light, you could be beamed up. It was all bricolage and arts and crafts. There was no technology, just beautiful ideas, this Utopian spaceship in Soho.

The area, mostly barren except for the fire station, would prove to be a perfect nexus for burgeoning youth culture, and was soon joined by two similarly oriented stores, Supreme and X-Girl. Rey moved to London and continued to contribute designs. NASA closed a year after its launch.

Gabriel Hunter (NASA promoter and doorperson): There was a vacuum that needed to be filled, and once the store opened, there was a spot again.

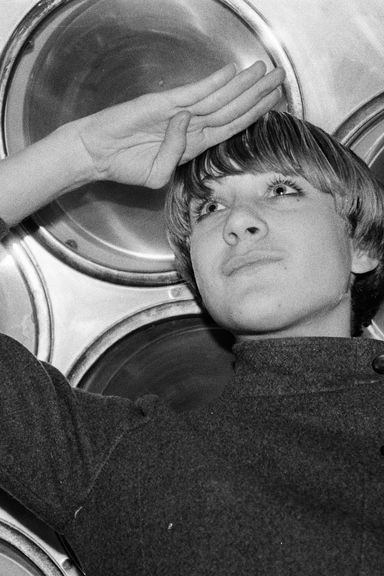

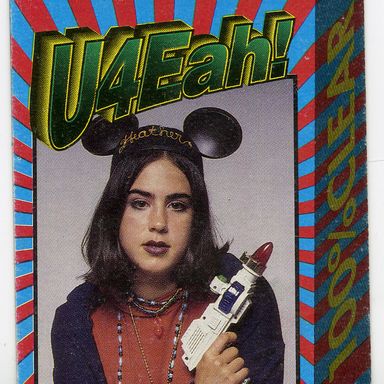

Glennon, Hunter, and their roommate, Sevigny, were hired at Liquid Sky, along with NASA alumnae Rebecca Tory and Carisa Barah. The staff was as curated as the stock, a distillation of the rave scene. Sevigny sewed labels on T-shirts.

Sevigny: That was one of my jobs at Liquid Sky — that, and juggling the cash register, and sending off the young kids that were bumming my cigarettes. You’d have to explain why the T-shirts were so expensive and just be kind of aloof, which I was very good at. I worked at a Ralph Lauren in high school, so I knew how to determine who was going to buy something or not. I was stoned most of the time, pretty mellow.

Glennon: Mary was the heart of the store, the mom. She was this beautiful woman who wasn’t in the rave scene but sort of into fashion, and kept Liquid Sky organized. Carlos was DJing all over the world.

Frey: I was there to keep the store on lockdown while they were raving.

Carisa Barah: We fought like a family, we hung out like a family— but a really good Partridge Family, singing-in-the-back-of-a-van kind of family. We’d party all night and then come in to work on two hours of sleep. My first job was sewing labels onto jackets. I put the patches on the wrong side on the first several dozen, so they made them limited edition.

Sidney Prawatyotin (fashion publicist and consultant): I discovered it during high school. You know those yellow “Safe Haven” stickers you would see in delis where kids could run away to protect themselves? Liquid Sky was my safe haven. I’d go there to cut class. Carlos, with those ski goggles and a long-sleeve white T-shirt with a Liquid Sky emblem and baggy pants, was untouchable in a way, like a wizard. I don’t think he went in with the intention of creating what he created, so that made it even more special and more organic. Who knew that the design studio in the back and the record store downstairs and the fashion in the front was going to create this scene?

As a subsidiary of Astralwerks, Liquid Sky started its own record label (which would later grow to include three imprints), which would release music by their growing DJ roster.

Sevigny: There were kids hanging out all the time. It was a spectacle. Having to be in there all day, every day, maybe I was more irritated by that. “You don’t work here. Go home.” But it was super fun. I loved what Astrogirl represented. She was kind of hopeful and positive. The heart vagina was so dope.

Jaime Perlman (creative director, British Vogue): Me and my best friend used to prank-call Liquid Sky all the time. Also there was a spiral staircase. A lot of people had platform shoes and it was difficult to go up and down, and this girl from my NYU dorm fell down them and broke her leg.

Sevigny: I wasn’t so into the music, so that was a struggle. I was into indie rock or punk. But I was into what Carlos was doing. Anybody that has that kind of passion is inspiring. I was into his music, as far as the techno genre, the jungle stuff. I performed in one of his shows at the Limelight once — Mary and I were the dancers, and I was terrible.

Frey: Calvin Klein, Polly Mellen, and all the fashion people would show up.

Since the store’s inception, it served as an outlet for emerging artists to refine their work. Dominating the décor were two chairs fashioned from grocery carts that were made by Tom Sachs, usually supporting a sprawling, coming-down raver. Rita Ackermann showed up with a notebook of sketches and was invited to collaborate. She drew a mural on the wall of a doe-eyed nymphet piloting a flying saucer, and did graphics on some clothes.

Mickey Boardman (editorial director, Paper): I bought the Rita Ackermann baby tee with the matching gold granny undies, which fit so weird because they were ladies’. I interviewed Hugh Grant for the magazine and had the T-shirt on. He said, “That’s a cool shirt, what is it?” I was like, “Oh, it’s Liquid Sky and I have the underwear to match.” I pulled down my pants.

Sevigny was already a downtown celebrity by the time Kids — also featuring cameos by Barah and Prawatyotin — came out in 1995. Its release would trigger a shake-up at the store.

Boardman: Chloë had a Buster Brown haircut and a one-shoulder orange bodysuit top. It was very advanced. That was seared into my mind as if I was seeing Madonna on the street.

Sevigny: Kids were coming into the store having seen the movie, and things went sour between Carlos and Mary. That was just the instance for me to be like, “I’m out of here, too.” I was not into the way things were going down between the two of them.

Rebecca Tory (Liquid Sky employee): Mary was an inspiration, but when she left, it allowed Gabe to grow.

Jennifer O’Donnell (photographer, Liquid Sky employee): It was the crescendo or plateau. I started in 1996. Carisa [Barah] trained me. She was about to film Gummo and had bleached eyebrows and hair. The core group — Peter, Rebecca, Carisa, and Chloë — had moved on. Gabe was still here designing.

Mara Hoffman (fashion designer): I was studying fashion at Parsons and worked at the counter. It was just this ‘90s phenomenon of aliens and good music. The aliens and the mission to see aliens, with Soul Slinger, it was real. We took a trip to Massachusetts to find them.

O’Donnell: The scene was changing. Kids that had been going out to raves, seven years later, weren’t doing the same. It wasn’t the same vibe. New York went through a humongous change with the whole Michael Alig thing. [Alig was charged with manslaughter in 1996.] That brought negative attention to a scene that was wildly free for so long. Clubs were getting shut down. As any scene that has some drug culture associated to it, people started to die. Even the music got dark.

Carlos painted over all the walls and the Rita Ackermann mural. It was our blue period — dark blue. Carlos wanted a complete and total change, to end that era and start a new one. Also, we were coming up on Y2K. There was a whole bunch of, this is the end of the century.

Final Home, a Japanese fashion brand with a more apocalyptic futurist vision, took over the space in 1999.

Carlos: I have no regrets in any shape or form because that’s what it was. Liquid Sky was based on utopia and chaos.

Carlos Soul Slinger had a child, moved to Brazil, then Arizona, and is back in New York. Claudia Rey is a fine artist. They resumed their working relationship and are looking for backers for a new Liquid Sky. A capsule collection was made for V-Files last year.

After leaving Liquid Sky, Frey opened Guru, a shaved-ice shop up the street named after her dog. There she met her husband Mario Sorrenti, whom she works with and has two children. She is also in Satan Ceramics, a pottery group, with Tom Sachs. Glennon manages an emergency room. Hunter is senior director of graphics for Gap Kids and Baby. Barah is a holistic health coach. Sevigny has held onto her “It”-girl mantle for a record 22 years.